Clinical record

Case 1

A 50-year-old woman presented with mild right upper quadrant (RUQ) pain 2 weeks after returning from Bali. This progressed over 1 month to severe epigastric pain, fever and rigors. She recalled eating mixed salad vegetables while in Bali. On ultrasound, multiple liver lesions were found and a diagnosis of pyogenic liver abscess was made. An infectious diseases (ID) physician was consulted. Her eosinophil count was raised (1.3 × 109/L [18%]; reference interval, 0.02–0.5 × 109/L). Microscopy of multiple stool samples did not show ova, cysts or parasites. Serological testing was positive for Fasciola hepatica (IgG optical density [OD], 3.0), and negative for Entamoeba spp. Hydatid antibodies were detected at a low titre (1 : 256) (this was considered to be a cross-reaction as confirmatory testing was negative). She had a good clinical response to oral triclabendazole 750 mg per month for 3 months.

Case 2

A 44-year-old woman developed diarrhoea during her stay in Bali, on a background of psoriatic arthropathy treated with leflunomide. While in Bali she frequently ate salads and uncooked vegetables. Her eosinophil count was normal (0.4 × 109/L [9%]). She developed RUQ pain 1–2 months after her return, and computed tomography (CT) imaging at 4 months showed a multifocal liver lesion with associated duct dilatation. She underwent a hemihepatectomy for presumed malignancy. Histopathological tests were non-diagnostic. An ID physician was consulted. Serological testing for F. hepatica was positive (IgG OD, 1.6). She was clinically cured with oral triclabendazole 750 mg monthly for 2 months.Clinical and diagnostic features of these two and four other cases are summarised in the Table, and selected images are shown in Figures A and B.

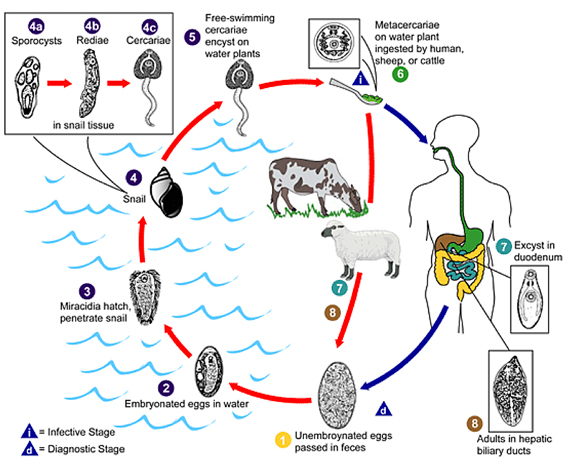

Fascioliasis is a foodborne infection caused by liver flukes Fasciola hepatica and F. gigantica. Transmission occurs from herbivores to humans via ingestion of cysts (metacercariae) present on water plants (classically watercress; see Box) or in contaminated water.1 Fascioliasis affects some of the world’s poorest communities. In the developed world, cases are mainly described in returned travellers, but infection may occur locally through ingestion of imported or locally grown vegetables.2

There are two distinct clinical phases of infection. The parenchymal liver phase is caused by larval migration through the liver, typically 6–9 weeks after infection. Clinically, this manifests as fever, RUQ pain, and eosinophilia. The ductal phase occurs as flukes enter the bile ducts and may cause obstructive jaundice or cholangitis.

Diagnosis among patients in this case series was delayed, with an average time from clinical presentation to diagnosis of 5.2 months. The patients we describe suffered considerable morbidity related to invasive investigations, surgery and delay in targeted antihelmintic therapy.

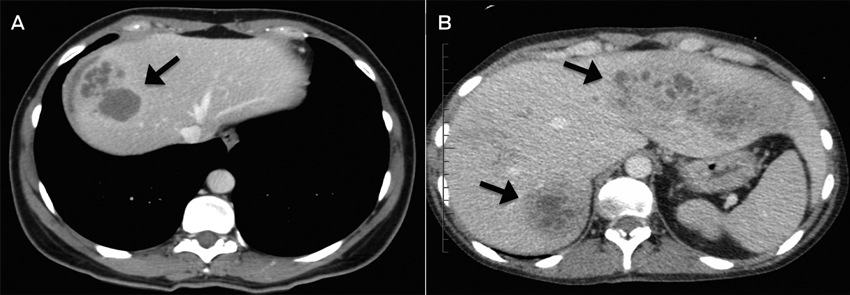

Radiological findings are often non-specific for fascioliasis. Ultrasonography and CT images often show poorly circumscribed lesions during the liver parenchymal phase.3

Once fascioliasis was considered in the diagnosis, fasciola serology was ordered and confirmed the diagnosis in all cases. The sensitivity and specificity using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) based on excretory-secretory antigen both exceed 95%.4 Results of serological testing may become positive 2–4 weeks after infection, preceding the presence of eggs in the stool. Serological testing is useful in travellers, but is of little use in residents of endemic areas, as it is difficult to differentiate past from present infection. Cross-reactivity with other helminths (as illustrated by these cases) is well recognised.5 We suspect these cases represent F. gigantica infection with antibodies being detected by the commercial ELISA based on F. hepatica antigens. In Australia, serological testing is only available at the Institute for Clinical Pathology and Medical Research in Westmead.

Normal eosinophil count cannot be used to exclude parasitic aetiology. Eosinophilia is more likely to be present during the parenchymal phase, however the eosinophil count may be normal in up to 50% of chronic cases.2 Stool microscopy did not yield positive results before treatment in these patients. It is not useful in the acute phase of illness, as the pre-patent period (time from infection to shedding of ova in the faeces by mature adult worms) is 4 months (Box).

Differentiating fascioliasis from other parasitic conditions is important, as the recommended management is specific. Triclabendazole in two separate treatments of 10 mg/kg per treatment is well tolerated and single dose cure rates exceed 80%.6,7 Resistance in humans has not yet been described. This drug is difficult to obtain in Australia for human use, and can either be imported or acquired through veterinary supply. Prescription requires Special Access Scheme approval and hospital ethics approval for use in humans.

Human cases of fascioliasis acquired in Bali have not previously been reported (Putra AA, Senior Veterinary Epidemiologist, Disease Investigation Centre, Denpasar, Bali, personal communication, 10 Dec 2013). These six patients were diagnosed between 2011–2014. Indonesia is the second most common destination for Australian travellers, with 1.01 million journeys in the 2013–14 financial year. This is a 266% trend change compared with the 2003–04 financial year.8 There are likely to be further cases affecting locals and tourists. Five of the six patients were women, perhaps reflecting a female preference for fresh salad. Women from endemic areas are recognised to be at higher risk than men, owing to exposure to contaminated water during washing and meal preparation.9 Two patients (Case 2 and Case 6) in this series were immunosuppressed, both receiving leflunomide for psoriatic arthritis. As co-exposed family members did not appear to contract fascioliasis, their immunosuppressed state may have contributed to their susceptibility.

The lack of human cases among locals in Bali to date may represent underdiagnosis, underreporting or perhaps a cultural difference in consumption of uncooked vegetables.

These patients are likely to have been infected with F. gigantica (rather than F. hepatica), as this is the predominant species in tropical regions, and up to 40% of Bali cattle are reportedly infected with F. gigantica (Putra AA, Senior Veterinary Epidemiologist, Disease Investigation Centre, Denpasar, Bali, personal communication, 10 Dec 2013). Species differentiation is possible based on the morphology of ova and worms, isoenzyme analysis or molecular techniques. F. hepatica could conceivably be transmitted by goats, but its prevalence in Bali is unknown.

Fascioliasis should be considered when a patient presents with RUQ pain, a poorly circumscribed lesion on imaging, eosinophilia (useful if present) and appropriate exposure history. A detailed travel and dietary history and an increased awareness of parasitic causes are important in facilitating timely referral to an infectious diseases or microbiology service for assistance with diagnosis and management.

Lessons from practice

- A detailed travel history should be obtained to assist in the differential diagnosis of liver lesions.

- Eosinophilia is suggestive of a parasitic cause of liver lesions; however, its absence does not rule this out.

- Serological testing is required to diagnose fascioliasis in a returned traveller.

Figure

A: Case 3; CT image showing multiloculated hepatic lesions (arrow), central cystic changes and necrosis. B: Case 2; CT image showing irregular lesions (arrows) through both left and right hepatic lobes.

Table

Characteristic |

Case 1 |

Case 2 |

Case 3 |

Case 4 |

Case 5 |

Case 6 |

|||||||||

Age in years, sex |

50, female |

44, female |

48, female |

45, female |

37, female |

58, male |

|||||||||

Symptoms on presentation |

RUQ pain, fever |

Diarrhoea, RUQ pain |

RUQ pain, fever |

Diarrhoea, RUQ pain |

RUQ pain, fever |

Malaise, fever |

|||||||||

Exposure |

Watercress |

Fresh salad |

Watercress |

Watercress |

Fresh salad |

Fresh salad |

|||||||||

Travel destination |

Bali |

Bali |

Bali |

Bali, Java |

Bali |

Bali |

|||||||||

Presumptive diagnosis |

Pyogenic liver abscess |

Malignancy |

Malignancy |

Pyogenic liver abscess |

Pyogenic liver abscess |

Pyogenic liver abscess |

|||||||||

Initial eosinophil count (absolute, %) |

1.3 × 109/L, 18% |

0.4 × 109/L, 9% |

1.1 × 109/L, 17% |

2.4 × 109/L, 32% |

0.0 × 109/L, 0 |

1.2 × 109/L, 26% |

|||||||||

Liver biopsy |

Not done |

Chronic inflammation |

No malignancy |

No malignancy |

Three, non-diagnostic |

Degenerate inflammatory cells |

|||||||||

Stool microscopy for ova, cysts and parasites |

Negative |

Negative |

Negative |

Negative |

Negative |

Negative |

|||||||||

F. hepatica serology |

Positive (IgG OD, 3.0) |

Positive (IgG OD, 1.6) |

Positive (IgG OD, 2.3) |

Positive (IgG OD, 2.8) |

Positive (IgG OD, 1.3) |

Positive (IgG OD, 23.9) |

|||||||||

Other positive serology (considered to be cross-reactivity) |

Hydatid, low titre |

Nil |

Strongyloides, Angiostrongylus, low titre |

Nil |

Strongyloides, low titre |

Schistosoma, low titre |

|||||||||

Time to diagnosis once medical attention sought |

3 months |

4 months |

4 months |

6 months |

2 months |

12 months |

|||||||||

Treatment |

Triclabendazole 750 mg immediately, repeat at 1, 2 months |

Triclabendazole 750 mg immediately, repeat at 1 month |

Triclabendazole 500 mg daily for 2 days |

Triclabendazole 750 mg immediately, repeat at 1 month |

Triclabendazole 500 mg daily for 2 days |

Triclabendazole 1 g immediately, repeat at 1, 2 months |

|||||||||

Outcome at 24 months |

Clinically well |

Clinically well |

Clinically well |

Clinically well |

Clinically well |

Recently diagnosed |

|||||||||

Life cycle of Fasciola species*

Fasciola eggs are released in the biliary ducts and faeces (1). Eggs embryonate in water (2), releasing miracidia (3), which invades the intermediate host, the snail (4). Parasites undergo development in the snail (sporocysts 4a, rediae 4b) maturing into cercariae (4c) which are released from the snail (5) and encyst as metacercariae on aquatic vegetation or other surfaces. Domestic or wild ruminants and humans can become infected by ingesting vegetation containing metacercariae (6). Metacercariae excyst in the duodenum (7), migrate through the intestinal wall, the peritoneal cavity, and the liver parenchyma into the biliary ducts, where they develop into adult flukes during a 3–4 month maturation period (8).

*Reproduced (diagram) and adapted (text) with permission from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.1

- 1. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites - fascioliasis (Fasciola infection). Atlanta: CDC, 2013. http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/fasciola/biology.html (accessed Nov 2014).

- 2. Fried B, Abruzzi A. Food-borne trematode infections of humans in the United States of America. Parasitol Res 2010; 106: 1263-1280.

- 3. Dusak A, Onur MR, Cicek M, et al. Radiological imaging features of Fasciola hepatica infection − a pictorial review. J Clin Imaging Sci 2012; 2: 2.

- 4. Hillyer GV. Serological diagnosis of Fasciola hepatica. Parasitol al Dia 1993; 17: 130-136.

- 5. Kaya M, Bestas R, Girgin S, et al. Increased anti-Echinococcus granulosus antibody positivity in Fasciola hepatica infection. Turkish J Gastroenterol 2012; 23: 339-343.

- 6. Keiser J, Utzinger J. Food-borne trematodiases. Clin Microbiol Rev 2009; 22: 466-483.

- 7. Cabada MM, White AC Jr. New developments in epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment and treatment of fascioliasis. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2012; 25: 518-522.

- 8. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Overseas arrivals and departures, Australia. Canberra: ABS, 2014. (ABS Cat. No. 3401.0.) http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/products/961B6B53B87C130ACA2574030010BD05?OpenDocument (accessed Jun 2015).

- 9. Mas-Coma S. Epidemiology of fascioliasisin human endemic areas. J Helminthol 2005; 79: 207-216.

No relevant disclosures.