Abstract

Objectives: To determine the incidence of abbreviation use in electronic hospital discharge letters (eDLs) and general practitioner understanding of abbreviations used in eDLs

Design, setting and participants: Retrospective audit of abbreviation use in 200 sequential eDLs was conducted at Nepean Hospital, Sydney, a tertiary referral centre, from 18 December to 31 December 2012. The 15 most commonly used abbreviations and five clinically important abbreviations were identified from the audit. A survey questionnaire using these abbreviations in context was then mailed to 240 GPs in the area covered by the Nepean Blue Mountains Local Health District to determine their understanding of these abbreviations.

Main outcome measures: Number of abbreviations and frequency of their use in eDLs, and GPs’ understanding of abbreviations used in the survey.

Results: 321 abbreviations were identified in the eDL audit; 48.6% were used only once. Fifty five per cent of GPs (132) responded to the survey. No individual abbreviation was correctly interpreted by all GPs. Six abbreviations were misinterpreted by more than a quarter of GPs. These were SNT (soft non-tender), TTE (transthoracic echocardiogram), EST (exercise stress test), NKDA (no known drug allergies), CTPA (computed tomography pulmonary angiogram), ORIF (open reduction and internal fixation). These abbreviations were interpreted incorrectly by 47.0% (62), 33.3% (44), 33.3% (44) 32.6% (43), 31.1% (41) and 28.0% (37) of GPs, respectively.

Conclusion: Abbreviations used in hospital eDLs are not well understood by the GPs who receive them. This has potential to adversely affect patient care in the transition from hospital to community care.

Deficits in discharge letters can contribute to a failure of information transfer. Studies have found high rates of omissions and errors in such letters.2-4 This contributes to errors in care after discharge. One study found that 49.5% of patients discharged from a large academic medical centre experienced at least one medical error relating to change of care on discharge.2

In this article, we focus on the potential danger of using abbreviations (shortened forms of words or phrases5) in medical communication. Abbreviations used in medical communications are either acronyms or initialisms. Acronyms use the initial letters of words and are pronounced as words (eg, ASCII, NASA); initialisms use initial letters pronounced separately (eg, BBC).5 Abbreviations are commonly used in medical specialties, but may not be understood by the broader profession. Doctors are under pressure to complete discharge letters in a timely fashion, and abbreviations may be used to facilitate this process.

We identified few published studies of the frequency of abbreviations in discharge letters.6,7,8 Some reported that abbreviation use is increasing and identified this as a concern. A recent audit at Royal Melbourne Hospital reported that 20.1% of all words in discharge letters were abbreviations.8 Another study audited abbreviation use in inpatient medical records and surveyed members of an inpatient multidisciplinary team for their understanding of abbreviations.9 The mean correct response rate was 43%, with Postgraduate Year 1 doctors posting the best scores (57%) and dietitians posting the worst (20%).

However, we identified no published studies determining whether the abbreviations used in hospital discharge letters are understood by GPs, who are usually the recipients of discharge letters.

Methods

We retrospectively analysed 200 electronic hospital discharge letters (eDLs) of patients discharged from Nepean Hospital, Sydney, a tertiary referral centre, from 31 December 2012, working backwards to 18 December 2012. We stopped at this point because few new abbreviations were being identified. To be included in the audit, an eDL had to be addressed to a GP.

We chose 31 December to begin the analysis to provide a representative sample of junior doctors who had a minimum of almost a year of hospital experience.

The meaning of each abbreviation was inferred from the surrounding text, and abbreviations were categorised as shown in Box 1.

Survey of GPs

From the audit, we developed a survey using the 15 most commonly used abbreviations plus five less frequently used but clinically important abbreviations. We determined that abbreviations of investigations, management or services were likely to be most clinically significant, based on our clinical experience and the potential consequences of misinterpretation. We defined commonly used abbreviations as those that were used at least 20 times in the audit. In the resulting survey of GPs, each abbreviation was provided in the context of a phrase in which it had been used in a discharge letter (Appendix).

To provide adequate precision, we aimed for 100 GP responses. The survey was mailed to all 240 GPs listed in the 2014 edition of the Medical Practitioners’ Directory for the Nepean, Blue Mountains and Hawkesbury areas. This was the most extensive directory of GPs in this area available to us. Responses were returned in a coded envelope inside a postage-paid envelope. GPs who did not respond were resent surveys on up to two additional occasions.

Outcome measures

Survey responses were analysed to determine what proportion of GPs understood each abbreviation.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Nepean Blue Mountains Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee.

Results

Electronic discharge letter audit

We found 321 different abbreviations in the 200 eDLs audited (a rate of 1.6 new abbreviations per eDL and 7.1 total abbreviations per eDL); most were initialisms. The frequency of abbreviations in eDLs is shown in Box 2.

Hospital coding-approved abbreviations accounted for 62.6% of all abbreviations identified. Seven unapproved abbreviations (2.2%) were in common use (ie, found more than 20 times in the audit).

GP survey

The response rate was 55% (132 of 240 GPs). No abbreviation was correctly interpreted by all GPs, but 10 abbreviations (50%) were interpreted correctly by 97.0% of GPs (128).

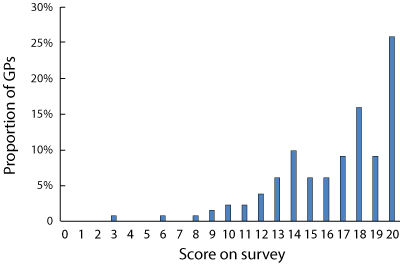

The frequency of incorrect interpretation of all abbreviations in the survey is shown in Box 3. Box 4 shows the range and frequency of individual GP scores.

Discussion

The results of our survey show that there is poor understanding among GPs of abbreviations used in hospital discharge letters. The response rate to our survey was fair, so our results are likely to be representative of GPs in the area.

Worryingly, more than half of the abbreviations we found related to investigations, management or services that we considered to be the most clinically significant categories. Misinterpretation of abbreviations by GPs can adversely affect patient care through duplication of investigations, failing to institute treatment based on investigation results or failing to follow up with recommended management. We could find no studies that identified which types of abbreviations confer the worst outcomes if misinterpreted. Also of concern is that almost half of the abbreviations we identified were used only once in the 200 eDLs.

The difference identified in the use of abbreviations by junior doctors and understanding of abbreviations by GPs suggests a lack of consistency between the language commonly used in hospitals and that used by GPs. It is uncertain how well understood these same abbreviations are by hospital doctors in different specialty areas. The language of abbreviations may also vary between hospitals. Common abbreviations found previously in Royal Melbourne Hospital discharge letters8 were different from those we found. The five most common inappropriate ambiguous or unknown abbreviations in the Royal Melbourne Hospital audit were not found in any eDL in our audit. Their abbreviation rate was higher, with a mean of 10.5 new abbreviations per discharge letter compared with our rate of 1.6. Widespread use of abbreviations in paediatric medical notes with no standardisation and difficulty in interpretation by health care professionals has also been previously reported.11

Our study has some limitations. Non-responding GPs might have scored differently on the survey compared with those who responded. Also, we did not ascertain GP demographic characteristics such as length of career outside the hospital setting. GPs with more recent hospital practice may better understand these abbreviations. In addition, we could not assess GPs’ understanding of most abbreviations we identified in the eDL audit because of the large number identified. However, we expect that understanding of these less frequently used abbreviations would be poorer than for the 20 we included in our survey. Also, this study was conducted in a single centre, so the results may not be generalisable to other centres. However, junior doctors are drawn from many universities and it is likely that discharge practices are similar in other hospitals.

Conclusion

Discharge letters are an essential means of communication between hospitals and GPs to facilitate optimal care of patients when they return to the community. All abbreviations used should be understood by all GPs. Strategies to improve communication by means of discharge letters are urgently needed. Potential solutions include banning the use of abbreviations in eDLs or using only a limited number of hospital-approved abbreviations and providing GPs with an approved abbreviation list. Another option would be use of computer software to auto-complete mutually exclusive abbreviations (ie, allowing only one possible meaning for each).

1 Categorisation of the 321 abbreviations used in 200 sequential electronic hospital discharge letters

Type of abbreviation |

Number |

% of total |

Representation of the types of abbreviation in the survey |

||||||||||||

Investigations |

102 |

31.8% |

30% |

||||||||||||

Physical examination finding |

56 |

17.5% |

30% |

||||||||||||

Management |

56 |

17.5% |

5% |

||||||||||||

Service* |

22 |

6.9% |

5% |

||||||||||||

Patient history |

20 |

6.2% |

30% |

||||||||||||

Other |

65 |

20.1% |

0 |

||||||||||||

Total |

321 |

100.0% |

100% |

||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

2 Frequency with which the 321 abbreviations were used in 200 sequential electronic hospital discharge letters

Frequency |

Number (%) |

||||||||||||||

> 20 times |

17 (5.3%) |

||||||||||||||

15–19 times |

5 (1.6%) |

||||||||||||||

10–14 times |

14 (4.4%) |

||||||||||||||

5–9 times |

32 (10.0%) |

||||||||||||||

0–4 times |

253 (78.8%) |

||||||||||||||

3 Frequency of incorrect interpretation by general practitioners of 20 common or clinically significant abbreviations

Abbreviations |

GPs misinterpreting abbreviation |

||||||||||||||

Number |

Percentage (95% CI)10 |

||||||||||||||

SNT |

62 |

47.0% (38.5%–55.5%) |

|||||||||||||

TTE* |

44 |

33.3% (25.3%–41.3%) |

|||||||||||||

EST* |

44 |

33.3% (25.3%–41.3%) |

|||||||||||||

NKDA |

43 |

32.6% (24.6%–40.6%) |

|||||||||||||

CTPA* |

41 |

31.1% (23.2%–39.0%) |

|||||||||||||

ORIF* |

37 |

28.0% (20.4%–35.7%) |

|||||||||||||

HSDNM |

31 |

23.5% (16.3%–30.7%) |

|||||||||||||

B/G |

31 |

23.5% (16.3%–30.7%) |

|||||||||||||

GCS* |

24 |

18.2% (11.6%–24.8%) |

|||||||||||||

ADLs |

18 |

13.6% (7.8%–19.5%) |

|||||||||||||

PMHx |

4 |

3.0% (0.1%–6.0%) |

|||||||||||||

CT |

4 |

3.0% (0.1%–6.0%) |

|||||||||||||

ECG |

4 |

3.0% (0.1%–6.0%) |

|||||||||||||

CXR |

4 |

3.0% (0.1%–6.0%) |

|||||||||||||

O/E |

4 |

3.0% (0.1%–6.0%) |

|||||||||||||

BP |

3 |

2.3% (0–4.8%) |

|||||||||||||

GORD |

3 |

2.3% (0–4.8%) |

|||||||||||||

RR |

2 |

1.5% (0–3.6%) |

|||||||||||||

ED |

2 |

1.5% (0–3.6%) |

|||||||||||||

HR |

2 |

1.5% (0.–3.6%) |

|||||||||||||

ADLs = activities of daily living. B/G = background. BP = blood pressure. CT = computed tomography. CTPA = computed tomographic pulmonary angiography. CXR = chest x-ray. ECG = electrocardiogram. ED = emergency department. EST = exercise stress testing. GCS = Glasgow coma scale. GORD = gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. HR = heart rate. HSDNM = heart sounds dual and no murmur. NKDA = no known drug allergies. O/E = on examination. ORIF = open reduction and internal fixation. PMHx = past medical history. RR = respiratory rate. SNT = soft, non-tender. TTE = transthoracic echocardiogram. | |||||||||||||||

Received 23 February 2015, accepted 19 June 2015

- Mark Chemali1

- Emily J Hibbert1

- Adrian Sheen3

- Mark Chemali1

- Emily J Hibbert1

- Adrian Sheen3

- 1 Nepean Hospital, Sydney, NSW

- 2 Sydney Medical School — Nepean, Sydney, NSW

- 3 Glenmore Park Medical Centre, Sydney, NSW

We thank Kristy Mann and Andrew Martin, biostatisticians from the National Health and Medical Research Council Clinical Trials Centre, for their contributions and statistical advice. Funding for postage of the surveys was provided by the Endocrinology Department at Nepean Hospital.

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, et al. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA 2007; 297: 831-841.

- 2. Moore C, Wisnivesky J, Williams S, McGinn T. Medical errors related to discontinuity of care from an inpatient to an outpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med 2003; 18: 646-651.

- 3. Jansen JO, Grant IC. Communication with general practitioners after accident and emergency attendance: computer generated letters are often deficient. Emerg Med J 2003; 20: 256-257.

- 4. McMillan TE, Allan W, Black PN. Accuracy of information on medicines in hospital discharge summaries. Intern Med J 2006; 36: 221-225.

- 5. Oxford University Press. Oxford dictionaries, 2015. http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/grow-op?q=abbreviatio (accessed Feb 2015).

- 6. Viana AA, de la Morena FJ. Abbreviations or acronyms in the internal medicine discharge reports. Study Group of the Quality of Information in Internal Medicine (Castilla-La Mancha)]. An Med Interna 1998; 15: 194-196. [Spanish]

- 7. Tulloch AJ, Fowler GH, McMullan JJ, Spence JM. Hospital discharge reports: content and design. Br Med J 1975; 4: 443-446.

- 8. Politis J, Lau S, Yeoh J, et al. Overview of shorthand medical glossary (OMG) study. Intern Med J 2015; 4: 423-427.

- 9. Sinha S, McDermott F, Srinivas G, Houghton PW. Use of abbreviations by healthcare professionals: what is the way forward? Postgrad Med J 2011; 87: 450-452.

- 10. McCallum Layton. Confidence interval calculator for proportions, 2015. https://www.mccallum-layton.co.uk/tools/statistic-calculators/confidence-interval-for-proportions-calculator/ (accessed Apr 2015).

- 11. Sheppard JE, Weidner LCE, Zakai S, et al. Ambiguous abbreviations: an audit of abbreviations in paediatric note keeping. Arch Dis Child 2008; 93: 204-206.

Ulf Steinvorth

We could of course just talk and write out what is important like they did in the olden days but OMG, LOL, gotta go, don't have time for that.

Competing Interests: No relevant disclosures

Dr Ulf Steinvorth

General Practice

Neil JamesShepherd

Competing Interests: No relevant disclosures

Dr Neil JamesShepherd

Crown Medical Practice