After-hours incentive funding was made available to accredited general practices in 1998 as a foundation component of the Practice Incentives Program (PIP). The PIP after-hours practice incentive payment was intended to “help resource a quality after hours service and compensate practices that make themselves available for longer hours, in recognition of the additional pressures this entails”.1 Funding for each participating practice was based on the formula shown in Box 1. The model thus predominantly focused on access to after-hours care and comprised four main components:

- a practice's standardised whole patient equivalent (SWPE) — the sum of the fractions of care provided to practice patients weighted for the age and sex of each patient

- how that practice ensured 24/7 care, from arranged external provision (stream 1) to self-provision only (stream 3)

- the location of the practice, based on its Rural, Remote and Metropolitan Areas (RRMA) classification

- the value per SWPE ($2).

In 2010, the PIP was audited by the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO).2 In an analysis of data provided by Medicare, the ANAO estimated that 14.9% of practices were non-compliant with respect to after-hours incentive payments between the financial years 2005–06 and 2008–09, the highest level of non-compliance across 12 PIP components. The Practice Nurse Incentive Program payments, at 9.5% non-compliance, were second highest. The ANAO investigated the potential of identifying practices at high risk of non-compliance for after-hours incentive payments in 34 practices deemed “high risk”. These practices were deemed high risk because of little evidence of actual after-hours service provision based on Medicare billings, while as stream 3 practices under PIP (Box 1), they were supposed to provide 24/7 care. On further investigation of these practices by random after-hours calls, only half provided at least a phone number at which a practice doctor could be contacted. The ANAO considered that secondary sources of information were imperative in ensuring practice compliance.

After-hours incentive funding and Medicare Locals

Under the aegis of the Commonwealth Government's 2011 national health reforms to promote local decision making, Medicare Locals were delegated responsibility for the funding and delivery of after-hours services in their constituencies from 1 July 2013. Each Medicare Local, including Tasmania Medicare Local (TML), had the opportunity to develop and/or implement the most applicable and relevant mechanism for their locale.

For TML, the local situation is complex as its constituency encompasses large urban practices through to small isolated practices across an entire state that is geographically challenging. Three factors led to TML's decision to continue the existing PIP after-hours funding arrangements in the 2013–14 financial year while simultaneously developing a preferred mechanism to be implemented in subsequent years: the complexities of the service environment; the desire to implement a fair, transparent and auditable mechanism; and the immediate need to provide after-hours incentive funding.

As part of the development process of the new after-hours incentive funding model, the PIP mechanism was interrogated to gain an understanding of the groundswell of disaffection for it among Tasmanian general practitioners. In this article, we describe the determination of the drivers of the PIP after-hours incentive funding model and the implications of this mechanism when viewed in context of the available (objective) Tasmanian after-hours data.

Drivers of the Practice Incentives Program mechanism: practice size, funding stream and location

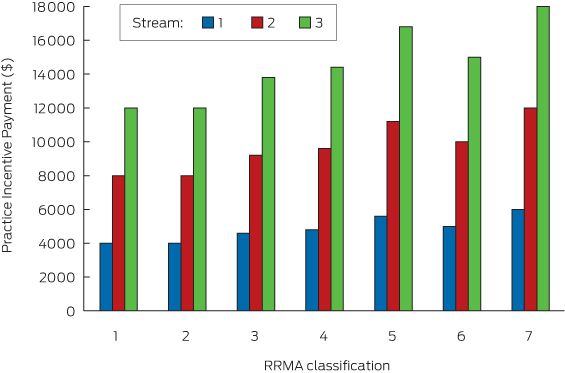

For a given-sized practice, the primary determinant of after-hours PIP was its stream as reflected in PIP payments calculated for a practice of 2000 SWPE by RRMA classification and stream (Box 2). The practice size of 2000 SWPE was chosen for simplicity and consistency with subsequent calculations. Stream could make up to a threefold difference in after-hours incentive payments for practices of the same SWPE and RRMA levels, as compared with a 1.5-fold difference for practices of a given SWPE and a given stream level located in the most disparate locales (RRMA 1/2 and RRMA 7).

Together, stream and location could give rise to a potential 4.5-fold difference in payments — in other words, the impacts are additive. For example, a practice with 2000 SWPE classified at RRMA 7 and stream 3 will have a PIP of $18 000 as compared with $4000 for the same-sized practice classified at RRMA 1/2 and stream 1.

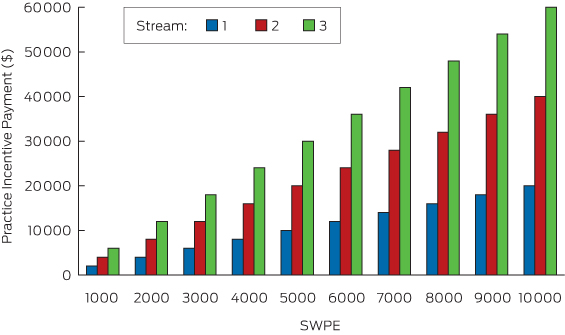

The greatest impact on after-hours PIP, however, was practice size, with payments directly proportional to individual practice SWPE as reflected in PIP payments calculated for practices in RRMA category 1 by SWPE and stream (Box 3). For example, the after-hours PIP for a stream 1 practice classified at RRMA 1/2 with 2000 SWPE is $4000 as compared with $20 000 for a similarly classified practice with 10 000 SWPE; a fivefold difference in practice size giving rise to a fivefold difference in after-hours PIP.

Thus, the PIP after-hours incentive funding mechanism was a multiplicative model primarily driven by practice size (SWPE), and in which the impacts of the claimed method of provision of after-hours care (stream) and location were additive, but of decreasing importance.

Implications

For the PIP after-hours incentive funding mechanism to fulfil its stated aim, practice size should therefore be the primary determinant of the burden and pressures faced by practices after hours, followed by stream and location. Given that the role of SWPE in PIP after-hours funding has been a major source of contention among Tasmanian general practices, the relative importance of practice size to after-hours burden is open to debate. Core questions include:

- how much does SWPE matter to after-hours on-call requirements and after-hours service provision?

- is it really the individual practice SWPE that matters?

- does one extra patient make that much difference during the on-call period or is the number of doctors available to share the burden of after-hours care a more relevant consideration?

Does size really matter? Insights from the 2013–14 Tasmanian After-Hours Practice Funding Scheme

The average full-time GP has been attributed a value of 1000 SWPEs annually.3 Given this accepted workload and to expedite subsequent analysis, the 92 Tasmanian practices in receipt of an after-hours incentive payment within the 2013–14 Tasmanian After-Hours Practice Funding Scheme (as at 31 December 2013), have been categorised into one of five SWPE bands, as specified in Box 4. The choice of SWPE bands in part reflects feedback received during the development of the Tasmanian General Practice After Hours Incentive Funding Model for 2014–15 that sustainable on-call care requires the availability of 4 or 5 full-time doctors. The breakdown was also supported by the distribution of Tasmanian general practices by practice size (SWPE) (individual data not shown due to commercial-in-confidence reasons). The average SWPE for Tasmanian practices was 3693.

Practices have also been classified under a new Tasmanian General Practice Location Classification (TGPLC), which was developed as a foundational element of the funding model given concerns about the applicability of the RRMA and other classifications in the Tasmanian context. The TGPLC is an eight-level classification: 1, major metropolitan centre; 2, major urban centre; 3, other urban centres; 4, urban fringe; 5, rural locations; 6, remote locations; 7, very remote locations; and 8, isolated.

Practice characteristics

In Tasmania, practice size becomes more restricted as level of remoteness increases. Large practices (SWPE bands 4 and 5) are only located in major urban locations (locations 1–3) under the TGPLC, whereas isolated areas only support small practices (SWPE band 1). Detailed data are not provided (due to commercial-in-confidence reasons). It is also evident that as practices become increasingly remote and isolated, the provision of 24/7 care becomes a necessity, with all practices in locations 7 and 8 of the TGPLC classified as stream 3. This observation arguably reflects the intent of stream 3, which was to support those practices that had no option but to provide 24/7 care.1 However, stream 3 practices occur in each TGPLC location category (1–8) and thus this categorisation does not of itself identify practices with unavoidable after-hours burden. In contrast, unavoidable after-hours burden is at least partially captured through a comprehensive and accurate location mechanism.

There was no obvious relationship between stream and practice size in Tasmanian practices providing after-hours care, with at least one practice from each SWPE band (1–5) represented in each stream (1–3). While any practice in SWPE band 3 or higher theoretically has the in-house capacity to provide sustainable 24/7 care (at least 4 or 5 full-time equivalent GPs), 23 of 35 stream 3 practices fall within SWPE band 1 or 2. These practices unquestionably face excessive on-call burden. Whether this burden is avoidable largely depends on the availability of viable alternative providers — that is, the existence of practices in the near vicinity to share the load.

Together, these data indicate the importance of determining the specific objectives of any after-hours incentive funding scheme and ensuring that the mechanism embodies those objectives — for example, support for (unavoidable) burden.

Performance by key determinants of Practice Incentives Program funding: practice size, funding stream and location

An analysis of objective data of after-hours service provision by general practices receiving after-hours incentive funding through TML provides further insights into the functioning of the 1998–2013 PIP after-hours funding scheme in relation to practice size, stream and location, and type of after-hours care.

Urgent after-hours attendances

Over the period 1 July 2013 to 31 December 2013, there is clear evidence that practice location, based on the TGPLC, has the strongest association with the number of urgent after-hours attendances per practice (Medicare item numbers 597 and 599), followed by stream. As assessed through simple linear regression, location explained 27% of the difference in urgent after-hours attendances between practices (P < 0.001) as compared with 9% for stream (P = 0.003). Practice size (SWPE band) had no explanatory value (R2 = 0.01; P = 0.39) (individual practice data not shown due to commercial-in-confidence reasons). The importance of practice location in the provision of urgent after-hours care is also reflected in the fact that the 18 practices located in non-urban localities (locations 5–8) accounted for almost two-thirds (926 of 1404) of urgent after-hours attendances.

On the basis of these results, and the fact that the most remote practices are smaller in size and stream 3 (on-call 24/7), rural and remote practices are, in general, facing greater burdens than urban practices after hours.

After-hours services to registered aged care facilities: a distinct form of after-hours activity

An interesting and marked contrast exists in relation to practice performance in the provision of care to immobile patients — for example, patients in residential aged care facilities (RACFs). First, the vast majority (2139 of 2423 [88.3%]) of after-hours RACF visits (Medicare item numbers 5010, 5028, 5049 and 5067) occurred in urban localities (locations 1–4) a finding consistent with the distribution of RACF bed numbers. Second, no relationship was found between increasing remoteness and number of after-hours RACF visits per practice (R2 = 0.00, P = 0.92), nor was a relationship found between number of after-hours RACF visits and a practice's stream (R2 = 0.01, P = 0.36). Some stream 1 practices gave rise to some of the highest levels of RACF visits, while otherwise ensuring urgent on-call access. For some practices, this activity may be arising due to formal arrangements with a nearby RACF. A relationship was, however, observed between number of RACF visits per practice and SWPE band, although it was limited, with practice size explaining 6% of the difference in number of RACF visits per practice between practices (P = 0.02). Some of the smallest practices gave rise to some of the highest levels of RACF visits (data not shown due to commercial-in-confidence reasons). Again, this could be due to formal arrangements.

Summary

Tasmanian data indicate that practice location is the primary predictor of on-call burden — that is, the burden increases as remoteness increases. Conversely, RACF visits, which are greater in number than after-hours attendances, predominantly occur in urban locations, but location is not a predictor of individual practice activity. Neither practice size (SWPE band) nor practice stream appear to be strong independent predictors of the provision of any form of after-hours care, although there are small positive trends for numbers of RACF visits and urgent on-call attendances. This trend reflects the fact that across SWPE bands and streams, there is a spectrum of providers (those that do and do not provide urgent care) and practices (ranging from those that provide minimal after-hours RACF visits to those that provide extensive after-hours RACF visits). These results were underpinned by relationships between location and stream (all very remote and isolated practices being stream 3), and between location and practice size (large practices > 6000 SWPE only being located in major urban locations).

Conclusion

The PIP after-hours incentive funding mechanism operating as at 30 June 2013 did not preferentially support practices that provide after-hours care. An after-hours incentive funding mechanism that recognises those practices that have no alternative but to provide 24/7 care is needed. Use of streams or tiers in the mechanism is considered inappropriate, potentially amounting to a perverse incentive. RACF visits should be considered an important but distinct form of after-hours care in an incentive funding mechanism. Finally, demands for transparency and use of auditable data are well justified.

4 Proportion of Tasmanian general practices in the After Hours Practice Funding Scheme by standardised whole patient equivalent (SWPE) band

SWPE band | SWPEs | No. (%) of general practices (n = 92) | |||||||||||||

1 | ≤ 2000 | 31 (33.7%) | |||||||||||||

2 | 2001–4000 | 30 (32.6%) | |||||||||||||

3 | 4001–6000 | 15 (16.3%) | |||||||||||||

4 | 6001–8000 | 10 (10.9%) | |||||||||||||

5 | 8001 + | 6 (6.5%) | |||||||||||||

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- Amanda L Neil1

- Mark R Nelson1

- Tracy Richardson2

- Meghan Mann-Leonard3

- Andrew J Palmer1

- 1 University of Tasmania, Hobart, TAS.

- 2 Tasmania Medicare Local, Ulverstone, TAS.

- 3 Tasmania Medicare Local, Hobart, TAS.

The Menzies Institute for Medical Research, University of Tasmania, was funded under contract to Tasmania Medicare Local to develop a new after-hours incentive funding model for Tasmania. The work described in this article was undertaken in the context of that work program.

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Medicare Australia. Practice Incentives Program. After hours incentive guidelines — August 2011. Canberra: Australian Government, 2011.

- 2. The Auditor-General. Practice Incentives Program, Department of Health and Ageing, Medicare Australia. Audit Report No.5 2010–11 Performance Audit. Canberra: Australian National Audit Office, 2010. http://www.anao.gov.au/uploads/documents/2010-11_Audit_Report_No5.pdf (accessed Jun 2015).

- 3. Medicare Australia. Practice Incentives Program (PIP) payments and calculations. Canberra: Australian Government, 2014.

Summary