Clinical record

A 47-year-old African American man was brought by his partner to the emergency department of a peripheral hospital with increasing confusion and a 1-week history of asthenia, anorexia and significant weight loss. Significant thirst, polyuria and nausea were not indicated by the corroborative history. He had no previous medical history and did not regularly take any medications. He had never smoked and his alcohol consumption was moderate. He had not travelled overseas recently. The patient's mother and maternal grandfather had both died of pancreatic cancer while still young, but this was not known at the time of his initial presentation.

The patient weighed 89 kg, with a body mass index of 26.0 kg/m2. His vital statistics were: heart rate, 130 beats/min; blood pressure, 99/60 mmHg; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min; pulse oximetry, 98% on room air; and tympanic temperature, 36.7ºC. He had ketotic breath and signs of severe hypovolaemia. Incoherent responses and disorientation with respect to both time and place were exhibited during neurological examination, but no focal neurological deficits. Cardiovascular, respiratory and abdominal examinations showed nothing unusual.

The results of his initial laboratory tests are listed in the Box. They were consistent with the diagnosis of first-onset diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) and profound hyperosmolar hypernatraemia. His estimated free water deficit was about 20 litres. His serum pancreatic enzyme levels were elevated, as were his C-reactive protein levels and white blood cell count. Chest radiography, electrocardiography, a urine drug screen, cerebral computed tomography (CT) and urine and blood cultures showed nothing unusual.

In light of the above findings, the patient was resuscitated with intravenous fluids, and insulin infusion was commenced for the treatment of DKA. Heparin was administered for the prophylaxis of venous thrombosis. He was then transferred to the intensive care unit of a tertiary referral centre for further investigation and care. His ketosis had resolved by Day 3 in the intensive care unit, and his serum sodium levels had gradually returned to normal by Day 6. At the same time, his mental functioning improved. The results of assays for diabetes-relevant autoantibodies (anti-glutamate decarboxylase and anti-islet cell antibodies) were negative, his glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) level was 10.9% (reference interval (RI), 4.0%–6.0%) and his C-peptide concentration was 1377 pmol/L (RI, 200–1200 pmol/L).

The elevated pancreatic enzyme levels prompted further investigation of his abdomen and pelvis with CT; the patient's acute renal dysfunction precluded the administration of intravenous contrast. The scan revealed a bulky pancreatic head with surrounding lymphadenopathy and multiple non-specific hypodensities in the liver. There was no radiological evidence of acute pancreatitis. Abdominal ultrasonography revealed numerous hypoechoic liver lesions consistent with metastatic disease. Levels of carbohydrate antigen 19-9 were markedly elevated (983 kU/L; RI, ≤ 37 kU/L), while the concentration of carcinoembryonic antigen was 18.1 µg/L (RI, 0–2.5 µg/L).

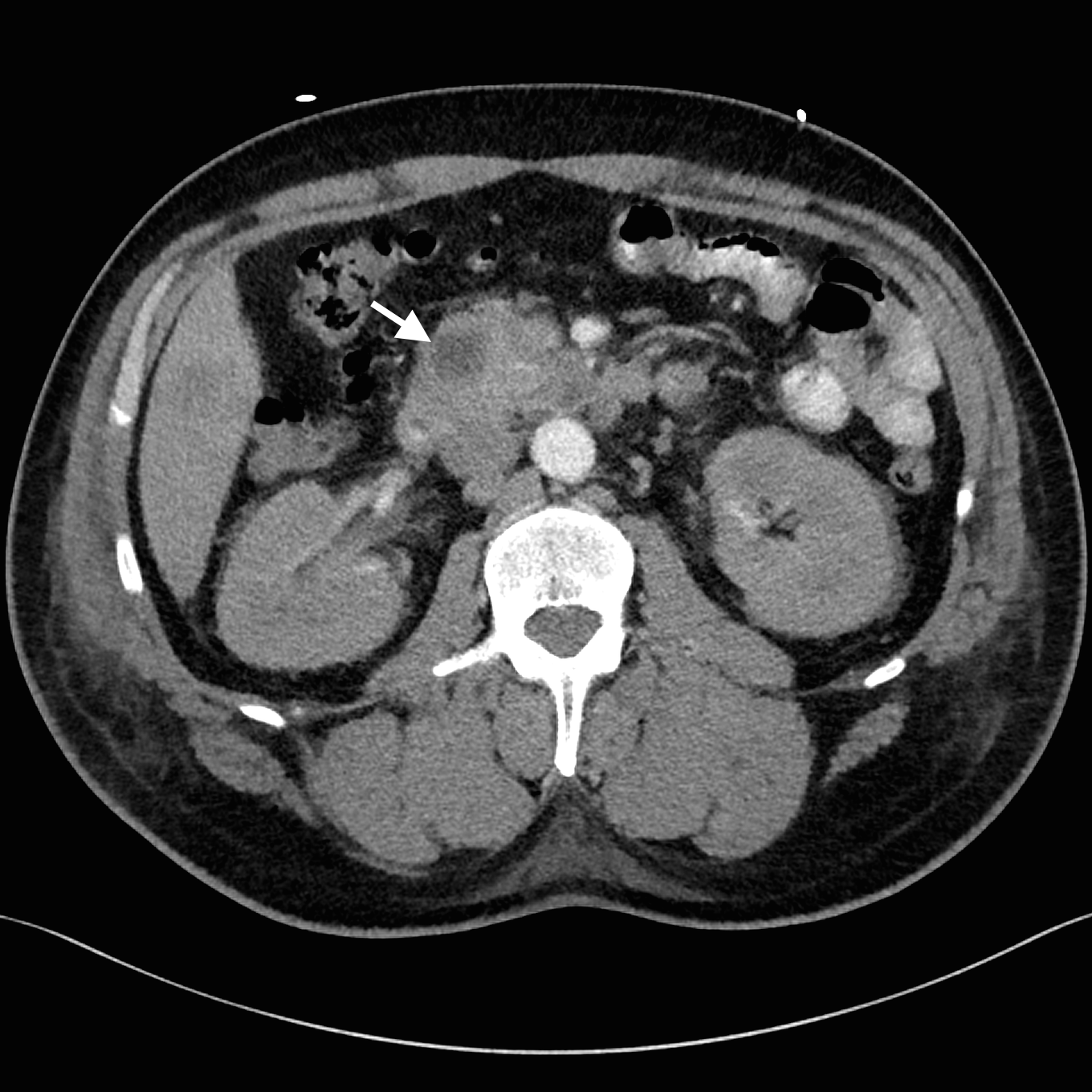

Despite adequate fluid replacement, the patient remained oliguric and developed deteriorating uraemia, so that haemodialysis was initiated. This facilitated further investigation with contrast-enhanced triple-phase hepatic CT, which confirmed a 25 × 23 × 17 mm heterogeneous head of pancreas mass, together with multiple hypodense liver lesions (Figure). Ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy of a liver lesion was performed. The cytological profile and immunohistochemical characteristics of the biopsy sample were consistent with metastatic adenocarcinoma, probably of pancreatic origin.

Palliative chemotherapy was considered, but the clinical condition of the patient deteriorated after the development of a pulmonary embolus and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy. He died on Day 35. Consent for an autopsy was not given.

Discussion

The hallmark of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is the triad of hyperglycaemia, ketonaemia and metabolic acidosis. The pathogenesis of DKA involves a relative insulin deficiency and an excess of counterregulatory hormones.1 Interplay between these factors results in reduced glucose utilisation and increased gluconeogenesis, together with increased lipolysis and ketogenesis.

DKA is classically associated with type 1 diabetes mellitus (DM1) but it has been increasingly recognised that it may also occur in type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2).2 Pancreatic adenocarcinoma presenting as DKA, however, is rare; only two other cases have been reported. The first involved a 75-year-old woman with longstanding DM2 who presented with DKA; pancreatic adenocarcinoma was later diagnosed.3 The second case was in a 36-year-old woman with a history of gestational diabetes; she presented with DKA associated with a pancreatic abscess that was later found to include pancreatic adenocarcinoma.4

Our patient was an otherwise healthy man who presented with first-onset DKA that led to the diagnosis of metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Despite the absence of a history of clinical symptoms, the elevated HbA1c and C-peptide levels, together with the absence of insulin autoantibodies, suggest that our patient may have had undiagnosed DM2. Further, our patient was African American, and an elevated incidence of DKA in African Americans with DM2 has been reported. In fact, studies have found that up to half of African American and Hispanic patients who developed DKA had features of DM2, referred to as “ketosis-prone DM2”.5,6 It has been hypothesised that the association of ketosis-prone DM2 with these ethnic groups reflects a genetic susceptibility to transient reductions in insulin production.5 The ethnicity of the two previous patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma-associated DKA was unfortunately not reported.

It has traditionally been assumed that the development of DKA in people with DM2 requires a stressful precipitating event. Recent studies, however, have found that there were no obvious triggers in up to 25% of people with DM2 who developed DKA.7 For our patient, there was no identifiable trigger apart from his pancreatic adenocarcinoma. It is possible that a pancreatic adenocarcinoma may itself have either paracrine or paraneoplastic effects that disrupt normal pancreatic endocrine function. Indeed, it has been shown that even transient insulinopaenia is sufficient to elicit DKA in ketosis-prone African American patients.8 It is not known whether this played a role in our patient, as insulin and C-peptide levels were not assayed when he was initially examined.

Finally, the diagnosis of pancreatic adenocarcinoma in our patient was somewhat fortuitous, as initial abdominal imaging was undertaken to investigate the elevation in his serum pancreatic enzyme levels. A definitive diagnosis was further delayed by the patient's acute renal dysfunction, which had initially precluded the use of intravenous contrast. A high degree of clinical suspicion of primary pancreatic disease is thus required when patients with features of DM2 present with first-onset DKA, especially if there are no apparent clinical triggers. Abdominal imaging may be warranted in these cases to look for less obvious precipitating events.

Lessons from practice

- Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) has classically been associated with type 1 diabetes but there is now increasing recognition of its occurrence in type 2 diabetes.

- It was previously assumed that relative insulinopaenia or stressful precipitating events were required to trigger DKA. Recent studies, however, indicate that there was no obvious precipitating factor in up to 25% of DKA cases in people with type 2 diabetes.

- DKA is more common in people from certain ethnic groups (including African Americans and Hispanics) with type 2 diabetes, termed ketosis-prone type 2 diabetes.

- If patients with type 2 diabetes present with DKA without any apparent trigger, abdominal imaging may be warranted to look for less obvious precipitating events.

Biochemical parameters of the patient immediately after his admission to hospital

Parameter | Value | Reference interval | |||||||||||||

pH | 7.21 | 7.36–7.44 | |||||||||||||

Paco2, mmHg | 33 | 35–45 | |||||||||||||

Pao2, mmHg | 96 | 80–100 | |||||||||||||

Actual bicarbonate, mmol/L | 13 | 22–30 | |||||||||||||

Base excess, mEq/L | – 14 | – 2 to +2 | |||||||||||||

Lactate, mmol/L | 2.3 | 0.5–1.6 | |||||||||||||

Sodium, mmol/L | 166* | 135–145 | |||||||||||||

Potassium, mmol/L | 4.8 | 3.5–5.0 | |||||||||||||

Chloride, mmol/L | 108 | 97–109 | |||||||||||||

Bicarbonate, mmol/L | 17 | 24–32 | |||||||||||||

Urea, mmol/L | 27.9 | 3–8 | |||||||||||||

Creatinine, µg/L | 391 | 70–110 | |||||||||||||

Calcium, mmol/L | 2.52 | 2.10–2.60 | |||||||||||||

Corrected calcium, mmol/L | 2.54 | 2.10–2.60 | |||||||||||||

Glucose, mmol/L | 64.8 | 3.0–7.7 | |||||||||||||

Ketone (point-of-care), mmol/L | 7.7 | < 3 | |||||||||||||

Osmolality, mEq/L | 480 | 280–300 | |||||||||||||

Albumin, g/L | 42 | 38–48 | |||||||||||||

Protein, g/L | 85 | 62–80 | |||||||||||||

Alanine aminotransferase (ALT), IU/L | 52 | 5–55 | |||||||||||||

Aspartate aminotransferase (AST), IU/L | 23 | 5–55 | |||||||||||||

Alkaline phosphatase (ALP), IU/L | 165 | 30–130 | |||||||||||||

γ-Glutamyl transferase (GGT), IU/L | 130 | < 60 | |||||||||||||

Bilirubin, µmol/L | 5 | < 21 | |||||||||||||

Amylase, IU/L | 653 | 20–120 | |||||||||||||

Lipase, IU/L | 1207 | 13–60 | |||||||||||||

Haemoglobin, g/L | 178 | 130–170 | |||||||||||||

Platelets, × 109/L | 300 | 150–400 | |||||||||||||

White cell count, × 109/L | 23.1 | 4–10 | |||||||||||||

Neutrophils, × 109/L | 18.9 | 2.0–7.0 | |||||||||||||

Lymphocytes, × 109/L | 0.9 | 1.0–3.0 | |||||||||||||

Monocytes, × 109/L | 1.4 | 0.2–1.0 | |||||||||||||

* Serum sodium corrected for hyperglycaemia is 192 mmol/L, using the formula in Banerji, et al.9 | |||||||||||||||

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- George Zhong1

- Rosalba Cross1

- Concord Repatriation General Hospital, Sydney, NSW.

We thank Sarah Abdo, Avi Suryawanshi and Nagesh Jadav for helpful discussions during the management of this case. We thank Caroline Fung for helpful discussions relating to the cytological and immunohistochemical findings, and Guy Harris for assisting with preparation of the radiological images.

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Chiasson JL, Aris-Jilwan N, Bélanger R, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis and the hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state. CMAJ 2003; 168: 859-866.

- 2. Linfoot P, Bergstrom C, Ipp E. Pathophysiology of ketoacidosis in Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med 2005; 22: 1414-1419.

- 3. Lin MV, Bishop G, Benito-Herrero M. Diabetic ketoacidosis in type 2 diabetics: a novel presentation of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Gen Intern Med 2010; 25: 369-373.

- 4. Lee KA, Park KT, Kim WJ, et al. Diabetic ketoacidosis as a presenting symptom of complicated pancreatic cancer. Korean J Intern Med 2014; 29: 116-119.

- 5. Umpierrez GE, Smiley D, Kitabchi AE. Narrative review: ketosis-prone type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med 2006; 144: 350-357.

- 6. Balasubramanyam A, Zern JW, Hyman DJ, Pavlik V. New profiles of diabetic ketoacidosis: type 1 vs type 2 diabetes and the effect of ethnicity. Arch Intern Med 1999; 159: 2317-2322.

- 7. Newton CA, Raskin P. Diabetic ketoacidosis in type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus: clinical and biochemical differences. Arch Intern Med 2004; 164: 1925-1931.

- 8. Banerji MA, Chaiken RL, Huey H, et al. GAD antibody negative NIDDM in adult black subjects with diabetic ketoacidosis and increased frequency of human leukocyte antigen DR3 and DR4. Flatbush diabetes. Diabetes 1994; 43: 741-745.

- 9. Hillier TA, Abbott RD, Barrett EJ. Hyponatremia: evaluating the correction factor for hyperglycemia. Am J Med 1999; 106: 399-403.

Jan Sheringham

Competing Interests: No relevant disclosures

Dr Jan Sheringham

N/A