In April 2014, in response to intravenous misuse of oral extended-release oxycodone hydrochloride, a new tamper-resistant formulation was released in Australia. We report a case of thrombotic microangiopathy after intravenous misuse of the new tamper-resistant formulation that was successfully managed without plasma exchange.

Clinical record

A 56-year-old man of European ancestry with no clinically significant medical history presented with a 3-day history of periumbilical abdominal pain. He admitted to daily intravenous (IV) misuse of oral extended-release oxycodone hydrochloride (OxyContin; Mundipharma) over a period of months. For the 5 weeks before presentation, he had been injecting the new tamper-resistant formulation because he was unable to access the discontinued crushable form.

On presentation, the patient was afebrile, had a pulse of 95 beats/min, blood pressure of 154/85 mmHg, a respiratory rate of 14 breaths/min and oxygen saturation of 97%. On examination, he had mild periumbilical tenderness. Results of cardiovascular and respiratory examinations were unremarkable. No murmur was detected. There was no injection site infection or axillary lymphadenopathy.

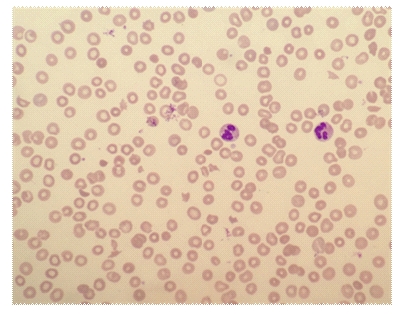

Laboratory investigations showed a haemoglobin level of 87 g/L (reference interval [RI], 135–180 g/L), a total white cell count of 15.0 × 109/L (RI, 4–11 × 109/L), a neutrophil count of 10.84 × 109/L (RI, 2–8 × 109/L), a monocyte count of 1.47 × 109/L (RI, 0.1–1.0 × 109/L) and a platelet count of 53 × 109/L (RI, 140–400 × 109/L). Electrolyte levels were normal, and serum creatinine level was normal at 66 µmol/L. The patient's unconjugated bilirubin level was 34 µmol/L (RI, < 20 µmol/L) and lactate dehydrogenase level was 769 U/L (RI, 150–280 U/L); other liver function test results were normal. His reticulocyte count was 168 × 109/L (RI, 10–100 × 109/L), haptoglobin level was 0.04 g/L (RI, 0.36–1.95 g/L) and Coombs test result was negative. Three per cent of his red blood cells were fragmented and polychromasia was present, consistent with microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia (Box 1). ADAMTS13 activity was 70% (RI, 40%–130%).

The patient's serological test results for hepatitis B, hepatitis C and HIV were negative. Vitamin B12, folate, lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin, anti-β2 glycoprotein I, antinuclear antibody, extractable nuclear antigen and complement levels were normal. His ferritin level was elevated at 442 µg/L (RI, 30–300 µg/L), and transferrin saturation was normal at 18%. Activated partial thromboplastin time and prothrombin time were normal and his fibrinogen level was elevated (5.4 g/L [RI, 1.7–4.5 g/L]). A random urine test showed a proteinuria level of 340 mg/L (RI, < 100 mg/L) and a protein-to-creatinine ratio of 66 g/mol (RI, < 15 g/mol).

We elected to manage the patient's condition conservatively without the use of plasmapheresis, steroids or antiplatelet agents. Spontaneous resolution of the microangiopathic haemolysis followed, and subsequent outpatient review showed that his parameters continued to normalise (Box 2).

To our knowledge, this is the first case of thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) associated with IV-administered reformulated OxyContin.

Discussion

Misuse of prescription opioids is an increasing problem in Australia. Morphine, oxycodone and methadone liquid are the most commonly misused prescription opioids, with injection being the route of administration in 75% of misusers.1 In response to these concerns, the National Pharmaceutical Drug Misuse Framework for Action (2012–2015) (http://www.nationaldrugstrategy.gov.au/internet/drugstrategy/Publishing.nsf/content/drug-mu-frm-action) has been developed, outlining various strategies to reduce misuse of pharmaceutical medications.

In April 2014, in response to IV misuse of OxyContin, a new crush-resistant formulation with the intent to deter inappropriate tampering and misuse of the drug was released in Australia, and supply of the old formulation was discontinued. The new tablets, which are embossed with “OP” (the original formulation was embossed with “OC”), are difficult to break, cut, crush or chew, and when added to water, form a viscous hydrogel, which cannot readily pass through a needle.

However, in the United States, where tamper-resistant OxyContin was introduced in August 2010, 24% of misusers reportedly found ways to inject the new formulation.2 Similarly, since its introduction in Australia, misusers presenting to the Sydney Medically Supervised Injection Centre have successfully injected the tamper-resistant formulation.3

TMA is a rare but serious blood disorder characterised by thrombosis in arterioles and capillaries that manifests clinically as a microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia and thrombocytopenia. Types of TMA include thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) or TMA associated with ADAMTS13 deficiency; haemolytic–uraemic syndrome (HUS) or infection-induced TMA; atypical HUS or TMA associated with disorders of complement; drug-induced TMA (Box 3); and TMA associated with other conditions including transplantation, lupus, glomerulopathies and malignant hypertension.4 For patients with TMA, HIV and other active viral infections should also be excluded.

Laboratory findings in TMA are consistent with non-immune haemolysis, including anaemia with high reticulocyte counts, elevated bilirubin and lactate dehydrogenase levels, reduced serum haptoglobin levels, red cell fragmentation and negative Coombs test results.

Treatment of TMA varies depending on the cause. Patients with TTP require plasma exchange, whereas HUS treatment is largely supportive. Atypical HUS is treated with plasma exchange and eculizumab, a monoclonal antibody that prevents C5 activation. Of the drug-induced TMAs, only ticlopidine-induced TMA has been shown to respond to plasma exchange. While determining ADAMTS13 levels assists in making a diagnosis, the decision to treat with plasma exchange is usually based on clinical history and other laboratory parameters, owing to the delay in obtaining this result and the necessity to start plasma exchange promptly.

Here, we report the first case of reformulated OxyContin-associated TMA and demonstrate that conservative management is a valid approach. While drug rechallenge would be required to prove a causal association, the temporal association with IV misuse of the reformulated OxyContin, the lack of alternative aetiologies, and the disease resolution with drug cessation indicate that the TMA was induced by the reformulated OxyContin. In addition, reformulated OxyContin is not the first reformulated drug to be associated with TMA. In August 2013, the US Food and Drug Administration and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued warnings regarding reformulated oral extended-release oxymorphone hydrochloride (Opana ER; Endo Pharmaceuticals; not available in Australia) after a link between IV Opana ER misuse and TMA was identified.5,6 Initial cases of reformulated Opana ER-induced TMA were treated with plasma exchange;7,8 however, subsequent reports have demonstrated that plasma exchange is unnecessary.9,10

In contrast to our case of OxyContin-associated TMA, acute kidney injury requiring haemodialysis was a prominent feature among patients injecting reformulated Opana ER.8 Our patient had a somewhat atypical presentation, with normal serum creatinine levels, minor proteinuria and no definitive evidence of other end-organ damage.

It is unclear what components of tamper-resistant OxyContin or Opana ER might trigger TMA and whether different methods of preparation can increase or decrease this risk. The new formulation of OxyContin contains inactive ingredients not found in the original formulation, including polyethylene oxide (PEO), butylated hydroxytoluene and magnesium stearate. Opana ER also contains PEO, and notably, in one study, rats intravenously injected with PEO subsequently became thrombocytopenic.11 Interaction with other prescription or illicit drugs is also a possibility. Our patient was taking sertraline 200 mg once daily and diazepam 5 mg as needed, and admitted to chronic daily marijuana use but denied any other substance misuse or medications.

Given the recent switch to tamper-resistant OxyContin in Australia, further cases of OxyContin-associated TMA may occur. A high degree of clinical suspicion is required to make this diagnosis, and we recommend that all patients presenting with TMA be questioned about the use of IV drugs. If OxyContin misuse is acknowledged, clinicians should consider conservative management, which avoids the morbidity and costs associated with plasma exchange.

2 Improvement in parameters throughout conservative management of thrombotic microangiopathy

Parameter | RI | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 5 | Day 6 | Day 9 | 3 months | ||||||

Haemoglobin (g/L) | 135–180 | 87 | 86 | 87 | 88 | 87 | 88 | 92 | 164 | ||||||

Platelet count (× 109/L) | 140–400 | 53 | 34 | 42 | 55 | 80 | 123 | 281 | 358 | ||||||

Unconjugated bilirubin (µmol/L) | < 20 | 34 | 22 | 30 | 24 | 18 | 8 | 10 | 10 | ||||||

Lactate dehydrogenase (U/L) | 150–280 | 769 | 870 | 889 | 858 | 688 | 611 | 439 | 221 | ||||||

RI = reference interval. | |||||||||||||||

- 1. Nielsen S, Bruno R, Degenhardt L, et al. The sources of pharmaceuticals for problematic users of benzodiazepines and prescription opioids. Med J Aust 2013; 199: 696-699. <MJA full text>

- 2. Cicero TJ, Ellis MS, Surratt HL. Effect of abuse-deterrent formulation of OxyContin. N Engl J Med 2012; 367: 187-189.

- 3. Silva S. Tamper-proof oxycodone failing. Medical Observer 2014; 6 Jun. http://www.medicalobserver.com.au/news/tamperproof-oxycodone-failing (accessed Oct 2014).

- 4. George JN, Nester CM. Syndromes of thrombotic microangiopathy. N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 654-666.

- 5. United States Food and Drug Administration. FDA warns about serious blood disorder resulting from misuse of Opana ER. 11 Oct 2012 and 1 Nov 2012. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm322432.htm (accessed Oct 2014).

- 6. Centers for Disease and Control and Prevention. Cluster of cases of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpure (TTP) associated with intravenous nonmedical use of Opanan ER. 26 Oct 2012. http://www.bt.cdc.gov/han/han00331.asp (accessed Oct 2014).

- 7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP)-like illness associated with intravenous Opana ER abuse – Tennessee, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2013; 62: 1-4.

- 8. Ambruzs JM, Serrell PB, Rahim N, Larsen CP. Thrombotic microangiopathy and acute kidney injury associated with intravenous abuse of an oral extended-release formulation of oxymorphone hydrochloride: kidney biopsy findings and report of 3 cases. Am J Kidney Dis 2014; 63: 1022-1026.

- 9. Kapila A, Chhabra L, Chaubey VK, Summers J. Opana ER abuse and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP)-like illness: a rising risk factor in illicit drug users. BMJ Case Rep 2014; Mar 3. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-203122.

- 10. Miller PJ, Farland AM, Knovich MA, et al. Successful treatment of intravenously abused oral Opana ER-induced thrombotic microangiopathy without plasma exchange. Am J Hematol 2014; 89: 695-697.

- 11. Karpova GV, Abramova EV, Lamzina TIu, et al. [Myelotoxicity of high–molecular-weight poly(ethylene oxide)] [Russian]. Eksp Klin Farmakol 2004; 67: 61-65.

No relevant disclosures