The suggestion that bald men are more virile than their well-thatched contemporaries is probably an old wives’ tale, but it must be conceded that old wives are likely to be unusually authoritative in this matter.1

John Burton and colleagues were the first to examine the contentious view that an association exists between virility and baldness in 1979. Notably Burton himself was balding at this time. However, the hypothesis has never been directly tested. In Burton et al’s study of 48 men aged 35–64 years, surrogate markers of “masculinity” such as hair density on the trunk and limbs, serum testosterone levels, sebum secretion rate, sweat secretion rate, skin thickness, muscle thickness and bone thickness showed no relationship to baldness.1 Virility per se was not assessed. Factors suggestive of a possible association include the lack of balding among eunuchs2 and pseudohermaphrodites,3 indicating that testosterone and its biologically active metabolite dihydrotestosterone are prerequisites for common baldness.4 Furthermore, the principal side effect of treatment of male pattern baldness with finasteride (a compound that prevents the conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone) is loss of libido and erectile dysfunction;5 and oral antiandrogen therapy is not used to treat androgenetic alopecia in men, as it has a profound inhibitory effect on the male libido, evidenced by its use to deliberately reduce sex drive in the treatment of deviant sexual behaviour in men.

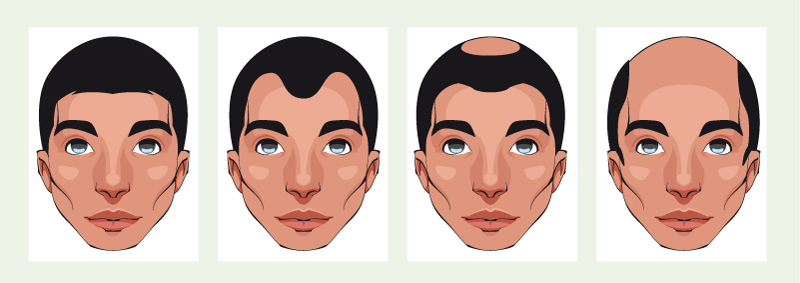

In order to resolve this vexing question, we used data from a study originally designed to examine risk factors for prostate cancer.6 This study was conducted in Australia between 1994 and 1997 in men under 70 years of age. Men with prostate cancer were recruited from cancer registers, and unaffected controls were recruited from electoral registers. All subjects were interviewed in person and were categorised into four patterns of baldness (nil, receding only, vertex only and fully bald) by the interviewer (Box 1). At the end of the interview, in private, subjects completed a questionnaire that elicited not only their history of ejaculations obtained by any means between the ages of 20 and 49 years but also their number of sexual partners.

Ethics approval for the use of the data in this study was obtained from cancer registry human research ethics committees in Victoria, New South Wales and Western Australia.

There were 2836 men who took part in the original study. Information on sexual function and sexual partners was available for 2205 men. We performed a secondary analysis of risk factors for baldness using unconditional logistic regression with baldness as the outcome and adjusting for age. As there were no differences in associations between baldness and virility in men with and without prostate cancer, we combined the data (Box 2).

No significant association was found between baldness (either limited to vertex balding at the crown or being fully bald) and the frequency of ejaculations between age 20 and 49 years (Box 2), but bald men were significantly less likely to have had more than four female sexual partners in their lifetime.

For our null findings to be explained by selection bias, we would have to postulate that relatively fewer virile bald men than non-virile bald men participated. Given that virility was not mentioned in any of the study information, and that virile men are likely to be participatory, this seems unlikely. Similarly, for reporting bias to have explained the null finding, would require that the virile bald men underreported the frequency of their ejaculations and non-virile men overreported. At the time the study was conducted, the myth that bald men are more virile was widespread, so we think it more likely that all participants would err on the side of societal expectations and overreport.

In the population we studied, bald men appear to be no more virile than their well thatched contemporaries. On the contrary, they seem to have fewer conquests. Although old wives may not be as authoritative on this matter as was once thought, it may be that bald men have earned this plaudit by being more faithful to them.

1 Examples of androgenetic alopecia patterns in men*

* Categorised in this study as (l to r) “nil”, “receding only”, “vertex only” and “fully bald”.

2 Risk of baldness and men’s average frequency of ejaculations between 20 and 49 years of age and their number of female sexual partners

|

Baldness |

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Not bald* |

Bald† |

Odds ratio (95% CI) |

P‡ |

|||||||||||

Weekly average ejaculations |

n = 532 |

n = 1673 |

|

0.55 |

|||||||||||

Up to average 2.3 times a week |

113 (21%) |

398 (24%) |

1.00 |

|

|||||||||||

Average 2.3–3.3 times a week |

118 (22%) |

330 (20%) |

0.86 (0.63–1.16) |

|

|||||||||||

Average 3.3–4.7 times a week |

110 (21%) |

350 (21%) |

0.99 (0.73–1.34) |

|

|||||||||||

Average 4.7–7 times a week |

103 (19%) |

341 (20%) |

1.08 (0.79–1.48) |

|

|||||||||||

More than 7 times a week |

88 (17%) |

254 (15%) |

0.90 (0.65–1.24) |

|

|||||||||||

Number of female sexual partners |

n = 520 |

n = 1625 |

|

< 0.001 |

|||||||||||

0–1 |

128 (25%) |

549 (34%) |

1.00 |

|

|||||||||||

2–4 |

58 (11%) |

221 (14%) |

0.90 (0.63–1.28) |

|

|||||||||||

5–14 |

118 (23%) |

318 (20%) |

0.71 (0.53–0.95) |

|

|||||||||||

15–29 |

100 (19%) |

245 (15%) |

0.68 (0.50–0.92) |

|

|||||||||||

30+ |

116 (22%) |

292 (18%) |

0.69 (0.51–0.92) |

|

|||||||||||

* Recorded by the interviewer as either “nil” or “receding only”. † Recorded by the interviewer as either “vertex only” or “fully bald”. ‡ P < 0.05 significant. |

|||||||||||||||

- Rodney D Sinclair1

- Dallas R English2

- Graham G Giles3

- 1 Department of Dermatology, Epworth Hospital, Melbourne, VIC.

- 2 Centre for Molecular, Environmental, Genetic and Analytic (MEGA) Epidemiology, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC.

- 3 Cancer Epidemiology Centre, Cancer Council Victoria, Melbourne, VIC.

The original research was funded by National Health and Medical Research Council Project Grant 450104: Markers of androgen action, genetic variations and prostate cancer risk.

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Burton JL, Ben Halim MM, Meyrick G, et al. Male-pattern alopecia and masculinity. Br J Dermatol 1979; 100: 567-571.

- 2. Hamilton JB. Effect of castration in adolescent and young adult males upon further changes in the proportion of bare and hairy scalp. J Clin Endocr Metab 1960; 20: 1309-1318.

- 3. Imperato-McGinley J, Guerrero L, Gautier T, Peterson RE. Steroid 5α reductase deficiency in man: an inherited form of male pseudohermaphroditism. Science 1974; 186: 1213-1215.

- 4. Hamilton JB. Male hormone stimulation is prerequisite and an incitant in common baldness. Am J Anat 1942; 71: 451-480.

- 5. Sinclair R. Male pattern androgenetic alopecia. Brit Med J 1998; 317: 865-869.

- 6. Giles GG, Severi G, Sinclair R, et al. Androgenetic alopecia and prostate cancer: findings from an Australian case-control study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2002; 11: 549-553.

Abstract

Objective: To test the popular assertion that bald men are more virile than their well thatched contemporaries

Design, participants and setting: Secondary analysis of data from a case–control study in a community setting between 1994 and 1997 among men below the age of 70 years, using in-person interviews and categorisation of baldness, with subsequent completion of a questionnaire by the participant. We analysed risk factors for baldness using unconditional logistic regression.

Main outcome measures: Baldness; history of ejaculations between the ages of 20 and 49 years; total number of sexual partners.Results: There was no significant association between baldness and the frequency of ejaculations, but bald men were significantly less likely to have had more than four female sexual partners.

Conclusions: In the population studied, bald men appear to be no more virile than their well thatched contemporaries.