Rates of smoking in pregnancy among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women are high,1-3 with 52% smoking during pregnancy compared with 15% in non-Indigenous Australian women.3,4 Smoking during pregnancy among Aboriginal women is inversely related to socioeconomic status,4 and in qualitative studies, Aboriginal women have nominated stress as a major reason for smoking.5,6 Indigenous women in other developed countries also have higher rates of smoking during pregnancy than women in the general population.7-9

As smoking rates in the general population have fallen in high-income countries, smoking has become more closely related to entrenched social disadvantage.10 A review of interventions for promoting smoking cessation during pregnancy10 showed that intervention was associated with a significant overall reduction in smoking during late pregnancy (risk ratio [RR], 0.94 [95% CI, 0.93–0.96]). The review suggested there was a need for studies to refine interventions to address the specific needs of disadvantaged subpopulations.10

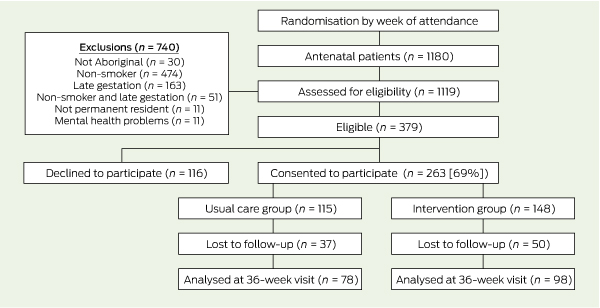

Women were considered eligible to participate in the study if they were Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islanders; were attending their first antenatal appointment at one of the Aboriginal community-controlled health services at or before 20 weeks’ gestation; were aged 16 years or older, were self-reported current smokers or recent quitters (quitting when they knew they were pregnant); and were residents of the local area. Recent quitters were included because there is evidence that such women often relapse, either later in pregnancy or after the birth.11,12 Women were excluded if their pregnancy was complicated by a mental illness or they were receiving treatment for chemical dependencies other than tobacco or alcohol use.

Women in the usual care group received general advice from their GP about quitting smoking, based on existing brief intervention guidelines.13

A Cozart microplate ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) test kit (Concateno, London, UK) was used for urine analysis. All samples were analysed in duplicate, with final results based on the average result of two paired wells. A woman was defined at follow-up as being a current smoker if (i) she reported that she had smoked in the previous 7 days; (ii) she reported that she had not smoked within the previous 7 days, but had a urine cotinine level of ≥ 250 ng/mL at the time; or (iii) she did not provide a urine sample.5

A flow diagram of randomisation and recruitment of trial participants is shown in Box 1. Of the 263 women who consented to participate, 148 were in the intervention group and 115 in the usual care group. Two-thirds of the women (176 [67%]) completed the outcome assessment: 98 (66%) in the intervention group and 78 (68%) in the usual care group.

Women in both groups were similar in terms of the median number of cigarettes smoked per day, number of weeks’ gestation at recruitment, and parity (Box 2). Compared with the usual care group, a slightly higher proportion of women in the intervention group were from Clinic 1, and a slightly lower proportion had a partner. The intervention group had a higher proportion of recent quitters than the control group. Consequently, we undertook a post-hoc subgroup analysis that included only those women classified as regular or occasional smokers at baseline.

In over 64% of intervention consultations, doctors adhered to the protocol in providing key components of the intervention. Lower proportions of nurses and health workers recorded that they had provided intervention advice (Box 3).

At 36-week follow-up, there was no significant difference in smoking rates between the two groups. Of the women followed up, 87 (89%) in the intervention group and 72 (95%) in the usual care group were smokers (RR for intervention versus usual care, 0.93 [95% CI, 0.86–1.08]; P = 0.212) (Box 4).

As expected, smoking rates were higher in the intention-to-treat analysis, with 137 smokers (93%) in the intervention group and 111 smokers (97%) in the usual care group (RR, 0.95 [95% CI, 0.90–1.01]; P = 0.207) (Box 4).

Subgroup analysis excluding baseline recent quitters showed no significant differences in smoking rates between the intervention group and the usual care group (P = 0.992) (Box 5). Corresponding figures for the intention-to-treat analysis were 123 smokers (99%) in the intervention group and 105 smokers (98%) in the usual care group (RR, 1.01 [95% CI, 0.98–1.04]; P = 0.965) (Box 5).

In our study design we estimated that women who received the intervention would have a 20% higher absolute quit rate than women in the control group. We based this estimate on the high proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women who smoked during pregnancy compared with non-Indigenous pregnant women. We expected to find that a large number of women would have lower levels of nicotine dependence and would be able to quit with intensive support. A previous study of Aboriginal people had shown high levels of motivation to quit among pregnant women compared with other adults.14 However, our expectations were not borne out by our results.

At baseline, there were more recent quitters in the intervention group than the control group. Post-hoc analysis of the subgroup of women that excluded baseline quitters showed that smoking rates in the intervention and usual care groups were more similar at follow-up than at baseline. This suggests that most of the non-smokers at follow-up were those who were recent quitters at baseline. One possible reason for this is that, in this population, once women quit smoking in pregnancy they tend to remain quitters for the duration of the pregnancy. This is contrary to previous evidence that women who quit smoking when they become pregnant are likely to relapse later in the pregnancy.11,12

2 Baseline characteristics of participants in the intervention and usual care groups*

Median number of cigarettes smoked per day (interquartile range) |

|||||||||||||||

Median number of weeks’ gestation at recruitment (interquartile range) |

|||||||||||||||

3 Compliance of doctors and health workers/nurses with the intervention protocol*

Health worker’s or nurse’s compliance at first antenatal visit |

|||||||||||||||

4 Number (%) of women smoking at ≥ 36 weeks’ gestation, based on cotinine validation of self-report:* complete outcome versus intention-to-treat analysis

Received 8 July 2011, accepted 14 March 2012

- Sandra J Eades1

- Rob W Sanson-Fisher2

- Mark Wenitong3

- Katie Panaretto4

- Catherine D’Este2

- Conor Gilligan2

- Jessica Stewart2

- 1 Indigenous Maternal and Child Health Research Program, Baker IDI Heart and Diabetes Institute, Melbourne, VIC.

- 2 University of Newcastle, Newcastle, NSW.

- 3 Apunipima Cape York Health Council, Cairns, QLD.

- 4 Queensland Aboriginal and Islander Health Council, Brisbane, QLD.

We wish to thank the pregnant Indigenous women who participated in our study and the collaborating Aboriginal health services (Wuchopperen Health Service, Cairns; Townsville Aboriginal and Islander Health Service, Townsville; and Derbarl Yerrigan Health Service, Perth). We also wish to acknowledge our project workers at each site: Nancy Stephens, Jasmin Cockatoo-Collins, Kaye Thompson, Lynette Anderson, Rozlyn Yarran and Joan Fraser. Our study was funded by National Health and Medical Research Council project grants 320851 and 510771 and program grant 472600.

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. de Costa C, Child A. Pregnancy outcomes in urban Aboriginal women. Med J Aust 1996; 164: 523-526.

- 2. Eades SJ, Read AW. Infant care practices in a metropolitan Aboriginal population. J Paediatr Child Health 1999; 35: 541-544.

- 3. Laws P, Sullivan EA. Australia’s mothers and babies 2007. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2009. (AIHW Cat. No. PER 48; Perinatal Statistics Series No. 23.) http://www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=6442468312 (accessed Apr 2012).

- 4. Thrift AP, Nancarrow H, Bauman AE. Maternal smoking during pregnancy among Aboriginal women in New South Wales is linked to social gradient. Aust N Z J Public Health 2011; 35: 337-342.

- 5. Gilligan C, Sanson-Fisher R, Eades S, et al. Assessing the accuracy of self-reported smoking status and impact of passive smoke exposure among pregnant Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women using cotinine biochemical validation. Drug Alcohol Rev 2010; 29: 35-40.

- 6. Wood L, France K, Hunt K, et al. Indigenous women and smoking in pregnancy: knowledge, cultural contexts and barriers to cessation. Soc Sci Med 2008; 66: 2378-2389.

- 7. Tipene-Leach D, Hutchison L, Tangiora A, et al. SIDS-related knowledge and infant care practices among Maori mothers. N Z Med J 2010; 123: 88-96.

- 8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Maternal, pregnancy, and birth characteristics of Asians and native Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders — King County, Washington, 2003–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2011; 60: 211-213.

- 9. Iyasu S, Randall LL, Welty TK, et al. Risk factors for sudden infant death syndrome among northern plains Indians. JAMA 2002; 288: 2717-2723.

- 10. Lumley J, Chamberlain C, Dowswell T, et al. Interventions for promoting smoking cessation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009; (3): CD001055.

- 11. Eades S. Bibbulung Gnarneep (Solid Kid): a longitudinal study of a population based cohort of urban Aboriginal children in Western Australia: determinants of health outcomes during early childhood of Aboriginal children residing in an urban area [PhD thesis]. Perth: University of Western Australia, 2003.

- 12. Najman JM, Lanyon A, Anderson M, et al. Socioeconomic status and maternal cigarette smoking before, during and after a pregnancy. Aust N Z J Public Health 1998; 22: 60-66.

- 13. Queensland Health. Smoke check — Indigenous smoking program. http://www.health.qld.gov. au/atod/prevention/smokecheck.asp (accessed May 2012).

- 14. Harvey D, Tsey K, Cadet-James Y, et al. An evaluation of tobacco brief interventions training in three indigenous health care settings in north Queensland. Aust N Z J Public Health 2002; 26: 426-431.

Abstract

Objective: To determine the effectiveness of an intensive quit-smoking intervention on smoking rates at 36 weeks’ gestation among pregnant Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women.

Design: Randomised controlled trial.

Setting and participants: Pregnant Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women (n = 263) attending their first antenatal visit at one of three Aboriginal community-controlled health services between June 2005 and December 2009.

Intervention: A general practitioner and other health care workers delivered tailored advice and support to quit smoking to women at their first antenatal visit, using evidence-based communication skills and engaging the woman’s partner and other adults in supporting the quit attempts. Nicotine replacement therapy was offered after two failed attempts to quit. The control (“usual care”) group received advice to quit smoking and further support and advice by the GP at scheduled antenatal visits.

Main outcome measure: Self-reported smoking status (validated with a urine cotinine measurement) between 36 weeks’ gestation and delivery.

Results: Participants in the intervention group (n = 148) and usual care group (n = 115) were similar in baseline characteristics, except that there were more women who had recently quit smoking in the intervention group than the control group. At 36 weeks, there was no significant difference between smoking rates in the intervention group (89%) and the usual care group (95%) (risk ratio for smoking in the intervention group relative to usual care group, 0.93 [95% CI, 0.86–1.08]; P = 0.212). Smoking rates in the two groups remained similar when baseline recent quitters were excluded from the analysis.

Conclusion: An intensive quit-smoking intervention was no more effective than usual care in assisting pregnant Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women to quit smoking during pregnancy. Contamination of the intervention across groups, or the nature of the intervention itself, may have contributed to this result.

Trial registration: Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry ACTRN12609000929202.