Pancreatic cancer is the fourth leading cause of cancer-related mortality in Australia.1 Median survival from diagnosis is about 5 months. The 5-year survival rate is less than 5%, but higher rates (between 6.8% and 17%) have been reported in those selected for surgery.2-4 Patients with unresectable disease have short survival times but benefit from palliative treatment.5,6 Results of resection and treatment in trials or published case series may not be achieved in clinical practice, as many patients are older and have more extensive disease than those included in randomised trials or referred to tertiary centres.

The Victorian Cooperative Oncology Group, in collaboration with the Victorian Cancer Registry (VCR), examined patterns of care for patients diagnosed with pancreatic cancer over a 2-year period. Here, we describe the surgical management of and outcomes for these patients. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy in this cohort have been described previously.7

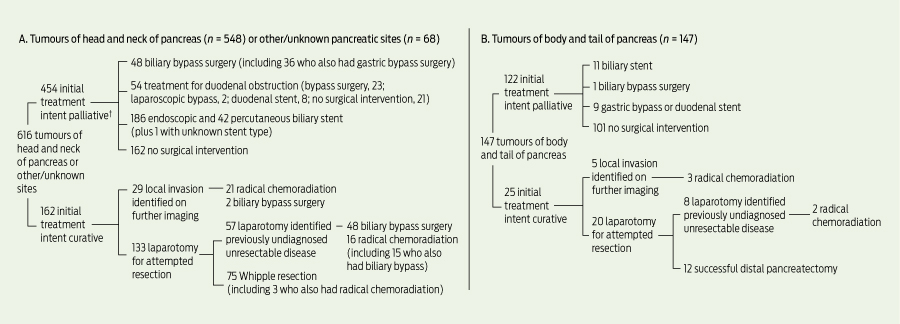

Surgical management of patients is shown in Box 1. Resection was performed in a total of 87 patients (11.4%).

A total of 99 patients, comprising two broad groups, had biliary bypass surgery (Box 1). In one group of 48 patients, unresectable disease was found during laparotomy for at-tempted resection, and bypass surgery was performed instead. Another two patients had bypass surgery after unresectable local invasion was shown on further imaging before laparotomy. In the other group of 49 patients, imaging identified more extensive disease, with metastases or local invasion, and bypass surgery was planned as an initial palliative procedure.

Biliary stents were the initial palliative treatment in 240 patients (Box 1) and were used to treat biliary obstruction occurring after initial treatment in 15 patients (13 after bypass surgery, two after Whipple resection). Biliary stents were used for preoperative drainage in 86 of 162 patients referred for Whipple resection.

Median survival and 30-day mortality for each treatment group are shown in Box 2.

Patients managed with Whipple resection had a median survival of 16.3 months (mean, 25 months); four patients (5.3%) died within 30 days, and seven (9.3%) within 90 days. Median survival of patients with positive margins was 13.9 months, compared with 20.6 months for those with clear margins (Box 3).

Compared with patients who had bypass surgery for initial palliation in unresectable disease, those having bypass surgery after being referred for Whipple resection had lower 30-day mortality (3.8% v 10.4%; P < 0.001), and better median survival (9.4 v 3.9 months; P < 0.001) (Box 2).

Patients who were managed conservatively with no surgical intervention had short survival and high 30-day mortality (Box 2).

The proportions of patients in each age group receiving various treatments are shown in Box 4. Compared with older groups, greater proportions of patients in younger groups underwent Whipple resection, chemoradiation, and gemcitabine treatment. Similar proportions of patients in the youngest and oldest age groups were managed with biliary stents and conservative treatment.

The management of carcinoma of the pancreas is often benchmarked on the results of surgical resection. Resection rates should be greater than 10% in unselected patients, and early mortality, observed median survival and 5-year survival are important end points.8,9 In this study, Whipple resection was performed in 12% of all patients presenting with tumours of the head and neck of the pancreas, comparable to reported rates of 10%–15%.9,10 Thirty-day mortality in these patients (5.3%) was comparable to reports from individual hospitals.9 A large epidemiological study in the United States reported 30-day mortality of 7.5%, and a survey of 23 hospitals in England and Wales reported 12%.11,12 Although inhospital or 90-day mortality are better measures of perioperative mortality, they are not as widely reported. Median survival in the patients undergoing Whipple resection in this study (16.3 months) is comparable with other reports, and their 5-year survival of 8% is comparable to results from a review of eight similar series (range, 3.7%–16.4%).9,13

We found that a relatively large number of surgeons each performed a modest number of Whipple resections during the 2-year study period, but early mortality and survival were not related to surgeon workload. However, investigations in larger populations have found that early mortality rate and survival improve with increasing workloads for both surgeons and hospitals.11 The US National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend pancreatic resection be done at hospitals that perform more than 20 resections annually.14 Chang and colleagues report excellent results from a high-volume centre in New South Wales and suggest most Whipple resections should be performed in high-volume specialist units.15 Implementation of this strategy has been difficult in other countries,16 and others argue that volume-based referrals undermine local expertise and may leave patients’ care far from supportive social networks, and therefore suggest that only high-risk patients be referred to high-volume centres.11

The proportion of patients in this study with positive resection margins (38.7%) was higher than in most other reports (14%–40%).17 Identification of involved resection margins depends on both the definition being used and the individual pathologist. In experienced hands, the rate of positive resection margins should be about 20%.18 As the rate of positive margins decreases with increasing workload,17 the higher rate in our study may be related to the low annual workload of most of the surgeons.

Twenty patients in our study (2.6%) survived at least 5 years. However, half of these patients were managed palliatively without histological confirmation of carcinoma and presumably represent false-positive diagnoses. A review of 23 3-year survivors found only 11 had histological confirmation of carcinoma, and cautioned that including patients without histological confirmation would falsely inflate the survival rate.19 Therefore, the actual 5-year survival in our study is best recorded as 10 patients (1.3%). A previous report of outcomes in Victoria found a more optimistic 5-year survival rate of 5%.2 The difference may be explained by lack of detailed clinical follow-up in that study, resulting in the inclusion of false-positive diagnoses reported to the VCR.

Unfortunately, 5-year survival does not equal cure. We found that disease recurred after 5 years in three of 10 patients treated with resection. During long-term follow-up after Whipple resection, one study found recurrent carcinoma in five of 12 patients between 5 and 6 years of follow-up, and another reported that four of 11 5-year survivors later died of recurrent disease.13,20 These findings suggest that 6-year survival is a better proxy for cure than 5-year survival.

Older age, more advanced disease, and poor performance status are significant predictors of poor survival.21-23 Comparisons of outcomes from different management strategies should be adjusted for the patient characteristics in each group. The influence of patient selection can be seen in the outcomes of bypass surgery in this study. Bypass patients who had been referred for Whipple resection but found to have unresectable disease at laparotomy were younger and had better outcomes than those referred initially for palliative surgery.

Guidelines recommend that biliary obstruction in frail elderly patients with limited life expectancy is best palliated with endoscopic stenting.8 Compared with bypass surgery, endoscopic stenting has been found to have lower early mortality and morbidity, although recurrent jaundice is more common due to stent blockages.24 In our study, bypass surgery was used as initial palliation for unresectable tumours in similar proportions of younger and older patient groups, including 6.6% of patients aged 80 years or older. The selection of elderly patients for bypass surgery may be due to patient preference for local management in regional hospitals or to difficulty accessing endoscopic stenting.

Chemotherapy with gemcitabine reduces symptoms, with a modest improvement in survival, and should be offered to all patients with advanced disease and good performance status.25 In this study, gemcitabine was used more often in younger patients with a good performance status, as judged by 30-day mortality. Other studies have found that a decreasing proportion of patients receive chemotherapy with advancing age.21 Our results have been reported in detail previously.7

An important question when discussing major surgery is: What is the chance of cure? A survey of oncologists and their patients in NSW found that 98% of patients would like realistic information about their prognosis.26 The rate of 5-year survival after Whipple resection is often quoted as about 20%.14,15 However, this outcome refers to those with a clear resection margin — a subgroup that can only be identified after surgery. The outcomes for all those undergoing a laparotomy for Whipple resection are more relevant for informing the process of consent before surgery. We found that these patients have a 5-year survival of 6%, but the 6-year survival (1.5%) is a more realistic estimate of the probability of cure. On the other hand, patients with tumours in the head or neck of the pancreas managed with best supportive care had median survival of only 2.3 months — much less than the overall median survival of 4.5 months — and benefit from early referral to palliative care.

1 Surgical management of patients with pancreatic cancer,* by site of tumour

† Patients may have received more than one type of treatment.

3 Survival of patients with carcinoma of head and neck of the pancreas, by subgroups reflecting progressively less extensive disease

Carcinoma of head and neck of pancreas or other/unspecified site (n = 616) |

|||||||||||||||

Received 13 July 2011, accepted 14 December 2011

- Antony G Speer1

- Vicky J Thursfield2

- Yvonne Torn-Broers2

- Michael Jefford3

- 1 Department of Gastroenterology, Royal Melbourne Hospital, Melbourne, VIC.

- 2 Cancer Epidemiology Centre, Cancer Council Victoria, Melbourne, VIC.

- 3 Division of Cancer Medicine, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Melbourne, VIC.

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Thursfield V, Farrugia H, Robertson P, Giles G, editors. Canstat No. 49: Cancer in Victoria 2008. Melbourne: The Cancer Council Victoria, 2010. http://www1.petermac.org/allg/NewSite/NewsEvents/canstatsVIC_08.pdf (accessed Feb 2012).

- 2. English D, Farrugia H, Thursfield V, et al. Cancer survival Victoria 2007. Estimates of survival in 2004 (and comparisons with earlier periods). Melbourne: The Cancer Council Victoria, 2007. http://www.cancervic.org.au/downloads/cec/survival-2007/Cancer-Survival-2007.pdf (accessed Feb 2012).

- 3. Nitecki SS, Sarr MG, Colby TV, van Heerden JA. Long-term survival after resection for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Is it really improving? Ann Surg 1995; 221: 59-66.

- 4. Sohn TA, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, et al. Resected adenocarcinoma of the pancreas-616 patients: results, outcomes, and prognostic indicators. J Gastrointest Surg 2000; 4: 567-579.

- 5. Bilimoria KY, Bentrem DJ, Ko CY, et al. Multimodality therapy for pancreatic cancer in the US: utilization, outcomes, and the effect of hospital volume. Cancer 2007; 110: 1227-1234.

- 6. Sener SF, Fremgen A, Menck HR, Winchester DP. Pancreatic cancer: a report of treatment and survival trends for 100,313 patients diagnosed from 1985–1995, using the National Cancer Database. J Am Coll Surg 1999; 189: 1-7.

- 7. Jefford M, Thursfield V, Torn-Broers Y, et al. Use of chemotherapy and radiotherapy in patients with pancreatic cancer in Victoria (2002–2003): a retrospective cohort study. Med J Aust 2010; 192: 323-327.

- 8. Pancreatic Section of the British Society of Gastroenterology, Pancreatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, Association of Upper Gastrointestinal Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland, Royal College of Pathologists, Special Interest Group for Gastro-Intestinal Radiology. Guidelines for the management of patients with pancreatic cancer periampullary and ampullary carcinomas. Gut 2005; 54 Suppl 5: v1-v16.

- 9. Beger HG, Rau B, Gansauge F, et al. Treatment of pancreatic cancer: challenge of the facts. World J Surg 2003; 27: 1075-1084.

- 10. Niederhuber JE, Brennan MF, Menck HR. The National Cancer Data Base report on pancreatic cancer. Cancer 1995; 76: 1671-1677.

- 11. Teh SH, Diggs BS, Deveney CW, Sheppard BC. Patient and hospital characteristics on the variance of perioperative outcomes for pancreatic resection in the United States: a plea for outcome-based and not volume-based referral guidelines. Arch Surg 2009; 144: 713-721.

- 12. Bachmann MO, Alderson D, Peters TJ, et al. Influence of specialization on the management and outcome of patients with pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg 2003; 90: 171-177.

- 13. Conlon KC, Klimstra DS, Brennan MF. Long-term survival after curative resection for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Clinicopathologic analysis of 5-year survivors. Ann Surg 1996; 223: 273-279.

- 14. Tempero MA, Arnoletti JP, Behrman S, et al; NCCN Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines for Oncology. Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2010; 8: 972-1017. http://www.jnccn.org/content/8/9/972.long (accessed Feb 2012).

- 15. Chang DK, Merret ND, Biankin AV; NSW Pancreatic Cancer Network. Improving outcomes for operable pancreatic cancer: is access to safer surgery the problem? J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008; 23: 1036-1045.

- 16. van Heek NT, Kuhlmann KF, Scholten RJ, et al. Hospital volume and mortality after pancreatic resection: a systematic review and an evaluation of intervention in the Netherlands. Ann Surg 2005; 242: 781-788.

- 17. Bilimoria KY, Talamonti MS, Sener SF, et al. Effect of hospital volume on margin status after pancreaticoduodenectomy for cancer. J Am Coll Surg 2008; 207: 510-519.

- 18. Adams RB, Allen PJ. Surgical treatment of resectable and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: expert consensus statement by Evans et al [comment]. Ann Surg Oncol 2009; 16: 1745-1750.

- 19. Connolly MM, Dawson PJ, Michelassi F, et al. Survival in 1001 patients with carcinoma of the pancreas. Ann Surg 1987; 206: 366-373.

- 20. Trede M, Schwall G, Saeger HD. Survival after pancreaticoduodenectomy. 118 consecutive resections without an operative mortality. Ann Surg 1990; 211: 447-458.

- 21. Krzyzanowska MK, Weeks JC, Earle CC. Treatment of locally advanced pancreatic cancer in the real world: population-based practices and effectiveness. J Clin Oncol 2003; 21: 3409-3414.

- 22. Shaib YH, Davila JA, El-Serag HB. The epidemiology of pancreatic cancer in the United States: changes below the surface. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2006; 24: 87-94.

- 23. Katz MH, Hwang R, Fleming JB, Evans DB. Tumour-node-metastasis staging of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. CA Cancer J Clin 2008; 58: 111-125.

- 24. Smith AC, Dowsett JF, Russell RC, et al. Randomised trial of endoscopic stenting versus surgical bypass in malignant low bileduct obstruction. Lancet 1994; 344: 1655-1660.

- 25. Burris HA 3rd, Moore MJ, Andersen J, et al. Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 1997; 15: 2403-2413.

- 26. Hagerty RC, Butow PN, Ellis PM, et al. Communicating with realism and hope: incurable cancer patients’ views on the disclosure of prognosis. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 1278-1288.

Abstract

Objective: To describe the management and outcomes of a population-based cohort of patients with pancreatic cancer in Victoria, Australia.

Design, setting and patients: Retrospective study based on questionnaires completed from medical histories of patients diagnosed with pancreatic cancer during 2002–2003 in Victoria who were identified from the Victorian Cancer Registry and followed up for 6 years.

Main outcome measures: Proportion of patients receiving each form of treatment, 30-day mortality, median survival, and 5-year and 6-year survival.

Results: Of 1044 patients with pancreatic cancer identified, 927 were eligible for the study, and questionnaires were completed for 830 (response rate, 89.5%); 67 patients with ampulla of Vater and neuroendocrine tumours were excluded. Of the 763 remaining patients (median age, 72 years), notification of death was available for 747 (97.9%). Most patients (n = 548) had tumours in the head and neck of the pancreas. Resection was performed in a total of 87 patients (11.4%). Patients managed with Whipple resection (n = 75) had a 30-day mortality rate of 5.3% and median survival of 16.3 months. A relatively large number of surgeons (n = 31) each performed a modest number of Whipple resections during the study period. Jaundice was palliated with biliary stents (n = 240) and bypass surgery (n = 99). Survival was shortest in those treated with best supportive care (median, 2.3 months for those with head and neck of pancreas tumours, and 3.4 months for body and tail of pancreas tumours). Of the 20 patients who survived to 5 years, 10 did not have histological confirmation of carcinoma and were presumably false-positive diagnoses, and three of the 10 patients who did have positive histological results had experienced recurrent disease by 6-year follow-up.

Conclusions: Most outcomes in Victoria compared favourably with other studies. Prognosis for patients with carcinoma of the pancreas is grim, with few long-term survivors. Six-year survival appears to be a better proxy for cure than 5-year survival.