Two children in far northern Western Australia tattooed their arms with maangga berries (Grevillea pyramidalis ssp. leucadendron), which resulted in unintentional, caustic, partial thickness skin burns requiring specialist burn care. An understanding of the chemistry of the burn agent (5-n-alkyl resorcinol), appropriate first aid management and referral, and possible physiological sequelae are essential for optimal medical management and preventive community education.

A 10-year-old Aboriginal girl with burns was referred to the Princess Margaret Hospital burns unit by a local general practitioner in far northern Western Australia. Relatively little was known about the nature of her burns or the potential toxic chemical sequelae and, because of the distances involved, it was decided to bring her to Perth. The patient had used local berries to “tattoo” both her forearms, causing bilateral caustic burns to 1% of her body surface area (Box 1, A). After consultation with the burns unit, the area was washed thoroughly with water to remove any remaining traces of caustic substance and the pH of the area was repeatedly tested. The berries had induced a partial thickness burn with blistering of the skin. The blisters were deroofed and washed and the pH checked again. The child was observed overnight for systemic and metabolic effects. The burns were initially treated with nanocrystalline silver dressing and hydrocolloid dressing, which were changed every 2 days (Box 1, B and C). These were later replaced with calcium alginate dressing and hypoallergenic polyacrylate adhesive, which were changed every 2 days until complete resolution 3 weeks later. The patient was advised to massage and moisturise the area and to use sunscreen protection.

Most caustic burns are secondary to accidental ingestion of a corrosive substance, causing significant oesophageal stricture or perforation, or from topical exposure to agricultural or building chemicals.1,2 According to some studies, almost half the burns described are in children (despite them comprising less than 3% of all burns), and burns have significant cultural and psychological sequelae.3,4

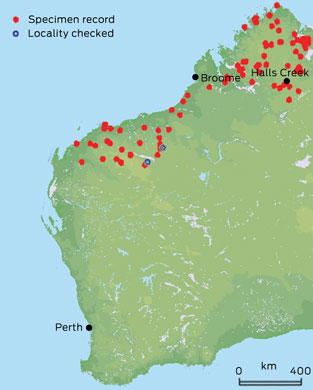

Excluding a few case series of self-inflicted garlic burns and fruit juice mouthwash gingivitis, as far as we are aware, no described cases exist of caustic burns from plant matter, especially plants that have cultural significance for the Aboriginal people of Australia.5 Of further interest is that the topical chemical burn also may have significant systemic consequences related to the burn chemical. Regional and national poisons centres were contacted for advice, but staff were unable to advise on the management of the patients because little is known about this berry internationally.

High-performance liquid chromatography has been used to isolate the corrosive substance, identified as 5-n-alkyl resorcinol, a phenol derivative, which is also a precursor for tetrahydrocannabinoid (the psychoactive chemical in marijuana). There has been a resurgence of interest in 5-n-alkyl resorcinol because of its antioxidant, antigenotoxic and cytostatic characteristics. It is a phenolic lipid metabolite of plants, animals, fungi and bacteria during normal development, as well as during times of stress, such as when infection or wounds are present or when the organism is affected by ultraviolet radiation. It has also been found to inhibit bacterial, fungal, parasitic and protozoal growth, and to reduce the efficacy of viral transfection.6 Chemical burning seems to occur when 5-n-alkyl resorcinol binds with proteins to form esters that irreversibly bind calcium. This interferes with cellular mitochondrial performance, leading to cellular anoxia and energy deprivation, causing protoplasmic poisoning and necrosis. This organic compound also binds and dissolves the lipid membrane of the skin cells, leading to proteinaceous structural disruption.

In a medical setting, naturally derived 5-n-alkyl resorcinol could be used as a potent heat shock protein-90 (Hsp-90) inhibitor. Hsp-90 is instrumental in the regulation of oncoproteins Her2, Akt, Bcr-Abl, c-Kit, EGFR and mutant BRAF, and when these oncoproteins are dysregulated, they lead to solid and haematological cancers.7 Clinically, Hsp-90 is the active compound in endodontic fillings and vascular glue and has been used extensively as a peeling agent.8

5-n-alkyl resorcinol has many side effects, including theoretical goitrogenic consequences, and G. pyramidalis is listed as poisonous in the United States Food and Drug Administration Poisonous Plant Database (http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/plantox/index.cfm). The fact that G. pyramidalis berry juice causes haemolysis is of concern, but the cardiac glycosides it contains may be of more concern, even though ingestion (not skin penetration) is required for a lethal dose. Other effects of cardiac glycosides include blurred vision, nausea, vomiting, bradycardia, confusion and lethargy, and people showing these signs after contact with G. pyramidalis should be referred to an emergency department immediately.

- 1. Palao R, Monge I, Ruiz M, Barret JP. Chemical burns: pathophysiology and treatment. Burns 2010; 36: 295-304.

- 2. Kay M, Wyllie R. Caustic ingestions in children. Curr Opin Pediatr 2009; 21: 651-654.

- 3. Dissanaike S, Rahimi M. Epidemiology of burn injuries: highlighting cultural and socio-demographic aspects. Int Rev Psychiatry 2009; 21: 505-511.

- 4. Jurkiewicz DJ, Krizek TK, Mathes SJ, Ariyan S, editors. Plastic surgery: principles and practice. St Louis: Mosby, 1990: 1355-1410.

- 5. Friedman T, Shalom A, Westreich M. Self-inflicted garlic burns: our experience and literature review. Int J Dermatol 2006; 45: 1161-1163.

- 6. Stasiuk M, Kozubek A. Biological activity of phenolic lipids. Cell Mol Life Sci 2010; 67: 841-860.

- 7. Porter JR, Fritz CC, Depew KM. Discovery and development of Hsp90 inhibitors: a promising pathway for cancer therapy. Curr Opin Chem Biol 2010; 14: 412-420.

- 8. Cassano N, Alessandrini G, Mastrolonardo M, Vena GA. Peeling agents: toxicological and allergological aspects. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 1999; 13: 14-23.

We thank the Western Australian Herbarium, Lynley Wallis and Paul Gioia for allowing us to use their images.

No relevant disclosures.