The prevalence of systemic allergy to native ant stings in Australia is as high as 3% in areas where these insects are commonly encountered, such as Tasmania and regional Victoria.1,2 In one large Tasmanian emergency department study, ant sting allergy was the most common cause of anaphylaxis (30%), exceeding cases attributed to bees, wasps, antibiotics or food.3

Myrmecia pilosula (jack jumper ant [JJA]) is the major cause of ant sting anaphylaxis in Tasmania.2 A double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial has demonstrated the effectiveness of JJA venom immunotherapy (VIT) to reduce the risk of sting anaphylaxis, and an ongoing treatment and research program has been established.4,5 Access to treatment outside Tasmania is limited by inadequate knowledge of the causative species in other regions and the absence of diagnostic tests for other ant species. Accurate diagnosis is further complicated because the JJA is a “species complex”, comprising seven closely related species with almost identical morphology. These were first recognised by chromosomal differences but can now be distinguished using subtle differences in morphological characteristics.6

Participants identified the responsible ant (where possible) from colour illustrations of common species and completed a questionnaire, followed by a structured telephone or face-to-face interview. We recorded participants’ age and sex, the geographical location where each reaction occurred, reaction features, a description of the insect and whether it was clearly seen to sting or implicated by circumstance (eg, seen nearby), and a reaction severity grade of mild (skin only), moderate (involvement of additional organ systems) or severe (hypotension or hypoxaemia).3 Serum samples were obtained and stored at − 80°C until analysis.

With the assistance of participants’ non-ant-allergic family or friends, 2–4 specimens of ant(s) were provided from each location where systemic reactions had occurred. Ants were not collected from the Northern Territory, northern Queensland or northern Western Australia because few participants came from these areas, nor from Tasmania, as ants in that region are already well characterised. Wherever possible, the investigators made field trips to collect additional specimens for identification and whole ant nests (colonies) for venom extraction from areas where stings had occurred. Ant colonies were transported on dry ice, then stored at − 80°C until venom sac dissection and processing, as previously described.4,7,8 Specimens were identified by one of us (R W T) and deposited in the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) Australian National Insect Collection.

After morphological identification, venoms extracted from different sibling species of the JJA species complex were analysed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis according to our previously established methods.9 Once homology of venoms from sibling species was confirmed, we used a standardised JJA extract produced by the Tasmanian Jack Jumper Allergy Program for our venom-specific IgE (sIgE) assays.7

A time-resolved fluorescence method, dissociation-enhanced lanthanide fluoroimmunoassay (DELFIA; Wallac, Turku, Finland),10 was used to detect sIgE against a panel of ant venoms relevant to each geographical region where sting reactions had occurred. Venom panels for sIgE testing were chosen for each region based on our collected specimens and known distributions.11,12 We were unable to include species if they were rarely encountered and we could not obtain sufficient venom.

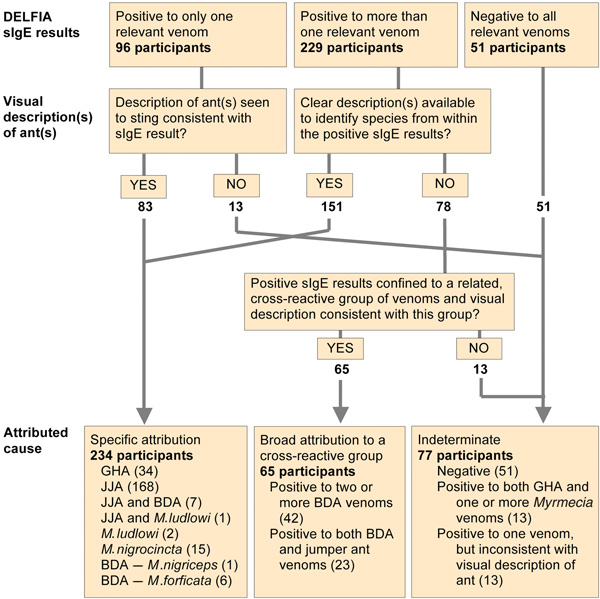

The cause of each reaction was attributed using a combination of ant identification and sIgE testing, as outlined in Box 1. A single positive sIgE result allowed us to confirm a clear ant description or, if there was some uncertainty about the ant(s) described, allowed us to decide between several possible causes. However, multiple positive sIgE results (representing either cross-reactivity or multiple sensitisations) required a high degree of clinical certainty (visual identification) before attributing causation.

Three hundred and seventy-six participants reported 735 systemic reactions. Basic demographic and reaction data are shown in Box 2. We identified 283 specimens of stinging ants collected from locations where reactions had occurred (Box 3). There were four dominant ant species or groups, each with characteristic morphology: (i) JJA species complex; (ii) other jumper ants (Myrmecia nigrocincta in New South Wales and Queensland, Myrmecia ludlowi in WA); (iii) bulldog ants (BDA) of the Myrmecia gulosa species group; and (iv) Rhytidoponera metallica (green-head ant [GHA]) (Box 4).

Venoms used for sIgE testing for each region are shown in Box 4. Serum samples from 325 participants (86%; 95% CI, 83%–90%) were sIgE-positive to one or more venoms relevant to the geographical regions where the stings occurred. Reaction causes were designated for 299 participants (80%; 95% CI, 75%–83%) (Box 1). For the remaining 77 participants (20%), 38 of whom were stung in northern Australia, a reaction cause could not be attributed.

The geographical locations of reactions to causative ants are mapped in Box 5. JJA reactions occurred in Tasmania, southern coastal WA, South Australia, Victoria and southern coastal and mountainous regions of NSW and the Australian Capital Territory. The distribution of JJA sting reactions closely mirrors that for entomological collection records of specimens of the M. pilosula species complex.12 Reactions to BDA occurred in the same areas as JJA reactions and also extended to more inland and northern parts of NSW and further north in WA, as far as Geraldton. M. ludlowi was also a cause of reactions in the areas where BDA were found in WA. M. nigrocincta and GHA reactions were largely clustered around northern coastal NSW and south-east Queensland.

We found Myrmecia species to be the predominant cause of ant sting anaphylaxis in Australia. JJA stings were the most common cause, followed by stings from species of BDA, the GHA, and then the jumper ants M. nigrocincta in northern NSW and Queensland and M. ludlowi in WA. While our findings are broadly consistent with a number of previous reports,1,2,13-16 this is the first time that it has been possible to confirm the causative species using sIgE testing against an extended panel of relevant venoms.

The causative species group could not be confirmed in 20% of cases, mostly due to negative sIgE results. Possible causes of this include allergy to less common species for which venom extracts were unavailable, and false negative results because of relatively poor sensitivity of serum sIgE assays compared with intradermal skin testing (IDT). The multicentre nature of our study precluded IDT, although it should be noted that this is also an imperfect test.17

While substantial antigenic cross-reactivity and/or multiple sensitisations to different venoms was observed,18 the frequency with which sera were positive to only one of the venoms or venom groups indicated the presence of venom allergens unique to each species. In particular, it should be noted that while the venoms of the various sibling species of the M. pilosula species complex appear to be homologous by gel electrophoresis, there are other jumper ants (M. nigrocincta and M. ludlowi) with very different venoms for which the currently available JJA venom extract will not be useful for diagnosis or VIT.

A major challenge we encountered was the large number of potentially allergenic venoms, allergenic cross-reactivity between venoms, and the potential for multiple sensitisations from stings by different species experienced by any one individual. This is not uncommon when assessing patients with insect venom allergy. Examining the ability of different venoms to inhibit sIgE binding to each other in each serum sample can distinguish the primary sensitising venom, identify allergenically identical venoms or confirm the presence of sensitisations to multiple venoms.19 However, sensitisation with demonstrable sIgE does not necessarily result in clinical reactivity.20 Thus, the presence of sIgE is only used to confirm a diagnosis that has been made from a clinical history including a description of the insect (if seen), circumstances of the sting and a detailed knowledge of local insect species.21

VIT is currently subsidised by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) in Australia for the treatment of honeybee and wasp (Polistes and yellowjacket) allergy. JJA VIT is currently funded in Tasmania by the state government; the venom extract can be supplied to interstate hospitals as an active pharmaceutical ingredient for on-site formulation and dispensing,22 but is not subsidised by the PBS and the cost must be covered in full by the hospitals and/or patients. No venom extracts suitable for human use are available for other Australian ant species at this time. Future work in this area should focus on confirming the apparent antigenic homology of closely related venoms and developing standardised venom extracts for diagnostic and therapeutic use.

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Received 25 November 2010, accepted 4 April 2011

- Simon G A Brown1,2

- Pauline van Eeden1

- Michael D Wiese3,2

- Raymond J Mullins4

- Graham O Solley5

- Robert Puy6

- Robert W Taylor7,8

- Robert J Heddle9

- 1 Centre for Clinical Research in Emergency Medicine, Western Australian Institute for Medical Research, Royal Perth Hospital, University of Western Australia, Perth, WA.

- 2 Jack Jumper Allergy Program, Royal Hobart Hospital, Hobart, TAS.

- 3 Sansom Institute, University of South Australia, Adelaide, SA.

- 4 Faculty of Health, University of Canberra, Canberra, ACT.

- 5 Watkins Medical Centre, Brisbane, QLD.

- 6 Department of Allergy, Immunology and Respiratory Medicine, Alfred Hospital, Melbourne, VIC.

- 7 Research School of Biology, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT.

- 8 CSIRO Division of Sustainable Ecosystems, Canberra, ACT.

- 9 Immunology Directorate, SA Pathology, Royal Adelaide Hospital and Flinders University, Adelaide, SA.

This work was funded by National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Project Grant 404050, NHMRC Career Development Award 513901 (Simon Brown), and grants by the Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy and the Fremantle Hospital Medical Research Foundation. We gratefully acknowledge the work of our research nurses who conducted interviews and research assistants who helped to collect nests, dissect venom sacs and prepare venom extracts (Pam Hudson, Ellen MacDonald, Sharon Marsden, Kevin Mullins, Judith Hawker, Dr Susan Aulfrey). Dr Karl Bleasel (Royal Melbourne Hospital) also assisted with enrolling participants from Victoria.

Raymond Mullins received unrestricted investigator-initiated grants for data purchase from CSL Limited and Alphapharm Australia (the past and current Australian distributors of EpiPen) and the Ilhan Food Allergy Foundation, Melbourne. Robert Heddle is employed by SA Pathology, which offers in-vitro diagnostic testing for specific IgE to jumper ant venom. Robert Taylor has received honoraria and travel support from the NHMRC.

- 1. Douglas RG, Weiner JM, Abramson MJ, O’Hehir RE. Prevalence of severe ant-venom allergy in southeastern Australia. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1998; 101: 129-131.

- 2. Brown SGA, Franks RW, Baldo BA, Heddle RJ. Prevalence, severity, and natural history of jack jumper ant venom allergy in Tasmania. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003; 111: 187-192.

- 3. Brown SGA. Clinical features and severity grading of anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004; 114: 371-376.

- 4. Brown SGA, Wiese MD, Blackman KE, Heddle RJ. Ant venom immunotherapy: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. Lancet 2003; 361: 1001-1006.

- 5. Brown SGA, Wiese MD, Chuter CL, Gunner J. Rapid (ultra-rush) versus clustered (semi rush) initiation of insect venom immunotherapy: an open randomised controlled trial with patient choice arms [abstract]. Intern Med J 2008; 38 Suppl 6: A151.

- 6. Imai HT, Taylor RW, Crozier RH. Experimental bases for the minimum interaction theory. I. Chromosome evolution in ants of the Myrmecia pilosula species complex (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Myrmeciinae). Jpn J Genet 1994; 69: 137-182.

- 7. Wiese MD, Milne RW, Davies NW, et al. Myrmecia pilosula (Jack Jumper) ant venom: validation of a procedure to standardise an allergy vaccine. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2008; 46: 58-65.

- 8. Wiese MD, Chataway TK, Davies NW, et al. Proteomic analysis of Myrmecia pilosula (jack jumper) ant venom. Toxicon 2006; 47: 208-217.

- 9. Wiese MD, Brown SGA, Chataway TK, et al. Myrmecia pilosula (Jack Jumper) ant venom: identification of allergens and revised nomenclature. Allergy 2007; 62: 437-443.

- 10. van Eeden PE, Wiese MD, Aulfrey S, et al. Using time-resolved fluorescence to measure serum venom-specific IgE and IgG. PLoS One 2011; 6: e16741.

- 11. Ogata K, Taylor RW. Ants of the genus Myrmecia Fabricius: a preliminary review and key to the named species (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Myrmeciinae). J Nat Hist 1991; 25: 1623-1673.

- 12. Shattuck SO, Barnett NJ. Ants down under. CSIRO, 2010. http://anic.ento.csiro.au/ants/ (accessed Nov 2010).

- 13. Clarke PS. The natural history of sensitivity to jack jumper ants (Hymenoptera Formicidae Myrmecia pilosula) in Tasmania. Med J Aust 1986; 145: 564-566.

- 14. Gilhotra Y, Brown SGA. Anaphylaxis to bull dog ant and jumper ant stings around Perth, Western Australia. Emerg Med Australas 2006; 18: 15-22.

- 15. Solley GO. Allergy to stinging and biting insects in Queensland. Med J Aust 1990; 153: 650-654.

- 16. Solley GO. Stinging and biting insect allergy: an Australian experience. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2004; 93: 532-537.

- 17. Golden DB, Kagey-Sobotka A, Norman PS, et al. Insect sting allergy with negative venom skin test responses. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001; 107: 897-901.

- 18. Street MD, Donovan GR, Baldo BA, Sutherland S. Immediate allergic reactions to Myrmecia ant stings: immunochemical analysis of Myrmecia venoms. Clin Exp Allergy 1994; 24: 590-597.

- 19. Hamilton RG, Wisenauer JA, Golden DB, et al. Selection of Hymenoptera venoms for immunotherapy on the basis of patient’s IgE antibody cross-reactivity. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1993; 92: 651-659.

- 20. Golden DB, Marsh DG, Kagey-Sobotka A, et al. Epidemiology of insect venom sensitivity. JAMA 1989; 262: 240-244.

- 21. Moffitt JE, Golden DB, Reisman RE, et al. Stinging insect hypersensitivity: a practice parameter update. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004; 114: 869-886.

- 22. Wiese MD, Davies NW, Chataway TK, et al. Stability of Myrmecia pilosula (Jack Jumper) Ant venom for use in immunotherapy. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2011; 54: 303-310.

Abstract

Objective: To determine the Australian native ant species associated with ant sting anaphylaxis, geographical distribution of allergic reactions, and feasibility of diagnostic venom-specific IgE (sIgE) testing.

Design, setting and participants: Descriptive clinical, entomological and immunological study of Australians with a history of ant sting anaphylaxis, recruited in 2006–2007 through media exposure and referrals from allergy practices and emergency physicians nationwide. We interviewed participants, collected entomological specimens, prepared reference venom extracts, and conducted serum sIgE testing against ant venom panels relevant to the species found in each geographical region.

Main outcome measures: Reaction causation attributed using a combination of ant identification and sIgE testing.

Results: 376 participants reported 735 systemic reactions. Of 299 participants for whom a cause was determined, 265 (89%; 95% CI, 84%–92%) had reacted clinically to Myrmecia species and 34 (11%; 95% CI, 8%–16%) to green-head ant (Rhytidoponera metallica). Of those with reactions to Myrmecia species, 176 reacted to jack jumper ant (Myrmecia pilosula species complex), 18 to other jumper ants (15 to Myrmecia nigrocincta, three to Myrmecia ludlowi) and 56 to a variety of bulldog ants, with some participants reacting to more than one type of bulldog ant. Variable serological cross-reactivity between bulldog ant species was observed, and sera from patients with bulldog ant allergy were all positive to one or more venoms extracted from Myrmecia forficata, Myrmecia pyriformis and Myrmecia nigriceps.

Conclusion: Four main groups of Australian ants cause anaphylaxis. Serum sIgE testing enhances the accuracy of diagnosis and is a prerequisite for administering species-specific venom immunotherapy.