On 8 June 2009, I started work as a locum gastroenterologist on the other side of the world and in a very different environment to the one I was used to. The inspiration for my visit came from an article in the careers supplement to the BMJ.1 A specialist trainee in infectious diseases wrote of his experiences working in Royal Darwin Hospital in the “Top End” of Australia’s Northern Territory. He described the hospital as modern and well equipped, but lacking a full-time gastroenterologist. On an impulse, I offered my services for 3 months, and my offer was accepted. I applied for a 3-month sabbatical — my first sabbatical — from my post of 18 years as a gastroenterologist at the Royal Victoria Hospital, Belfast, and a senior lecturer at Queen’s University Belfast, Northern Ireland, United Kingdom.

Although about 30% of the NT population are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, most living in remote areas, they make up a disproportionate 40%–60% of the patient population at the hospital. This reflects the relatively poor health status of Indigenous Australians compared with the non-Indigenous population. Their high level of diabetes, chronic renal disease, hypertension, heart failure and alcoholism is a disturbing fact, as is their lower life expectancy; the life expectancy gap at birth between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people is 12 years for males and 10 years for females.2 Furthermore, perinatal and infant mortality rates are two to three times non-Indigenous rates.2 My stay helped me to appreciate the complex reasons for this situation, which encompass social and economic as well as educational factors, not to mention the difficulties of delivering health care to remote communities.

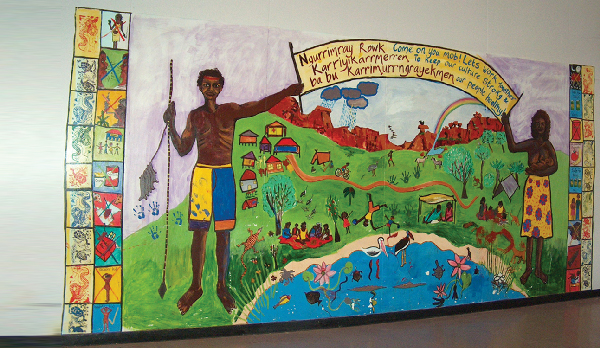

Of particular value were the hospital’s cultural awareness seminars, which enabled new staff to gain some understanding of the culture of Indigenous people. The key points that I gained from these seminars were an appreciation of the complexity and richness of Aboriginal culture, and the profound personal disruption for Aboriginal people that admission to hospital entails. Hospital admission is traumatic for anyone, but for people who live in small, isolated communities with strong family relationships, it is deeply disturbing and bewildering. First, they have to cope with being unwell, and then with being flown several hundred kilometres to a place which must seem alien in virtually every respect — uncomfortably cold air-conditioning, different food, a different language, and frightening procedures. I learnt that even small things like eye contact, which we regard as a polite courtesy when talking to another person, may be threatening and confrontational to Aboriginal people. Great efforts are made to bridge this cultural gap by providing interpreters and Aboriginal liaison officers, and by encouraging a friend or relative to travel with patients and stay with them at the hospital.

- 1. Maude RJ, Currie BJ. Tropical medicine in the Top End. BMJ Careers 2007; 25 August. http://careers.bmj.com/careers/advice/view-article.html?id=2553 (accessed Sep 2010).

- 2. Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision. Overcoming Indigenous disadvantage. Key indicators 2009. Overview. http://www.pc.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/90129/key-indicators-2009.pdf (accessed Sep 2010).

I would like to thank Dr Diane Howard, consultant physician at Royal Darwin Hospital, for enabling me to take up the post of locum physician. I acknowledge the support of the NT Government for my travel and accommodation expenses as part of my employment package.

None identified.