West Nile virus is an arbovirus that has caused large outbreaks of febrile illness, meningitis and encephalitis in Europe, North America and the Middle East. We describe the first laboratory-confirmed human case of West Nile virus infection in Australia, in a 58-year-old tourist who was almost certainly infected in Israel. The case is a reminder of the need to consider exotic pathogens in travellers and of the risk of introducing new pathogens into Australia.

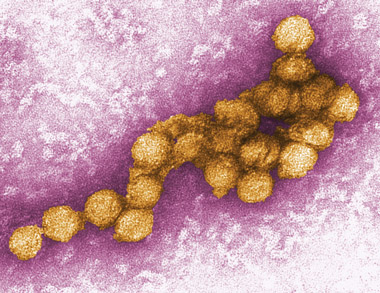

Paired sera from Day 9 and Day 31 of the illness were tested in parallel in a flavivirus group-reactive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for IgG and IgM. This showed a fourfold rise in IgG titre, and IgM seroconversion. The sera were then tested against a panel of flaviviruses for total antibody (by neutralisation) and for IgG and IgM (by immunofluorescence). The strongest reaction by immunofluorescence was against the New York 99 strain of West Nile virus (WNV; Box 1); seroconversion to this virus was confirmed by neutralisation (“gold standard”) tests (Box 2).

WNV is a single-stranded RNA flavivirus that was first isolated in 1937 from a patient with fever in the West Nile District of Uganda.1 The virus exists in a bird–mosquito–bird cycle, with wild birds as the amplifying host and reservoir.2 It has been isolated from 43 species of mosquito, mostly bird-feeding members of the Culex genus. Humans and other mammals are incidental hosts, when bitten by infected mosquitoes.

Since first described, WNV has spread widely, with an associated dramatic increase in disease severity.3,4 It is found in Africa, Europe and the Middle East, with large outbreaks identified during the past decade in Romania, North America and Israel.5-7

About 80% of patients with WNV infection are asymptomatic. The incubation period for symptomatic disease is 2–14 days. “West Nile fever” is a non-specific febrile illness that includes headache, myalgia, and occasional gastrointestinal symptoms and usually resolves spontaneously in less than a week.8 Acute neurological illness is uncommon, occurring in fewer than 1% of infections, and can present with meningitis, encephalitis or a poliomyelitis-like acute flaccid paralysis.9

Our patient was almost certainly infected in Israel, where WNV is endemic, with episodic outbreaks reported since the 1950s, most recently in 2000.7 Israel is the likely origin of the WNV strain now circulating widely in North America.6

The most frequent arboviral cause of encephalitis in Australia is Murray Valley encephalitis virus, which is endemic in northern Western Australia, the Northern Territory and northern Queensland, and has epidemic activity in southern Australia.10 Less common arboviral causes of locally acquired encephalitis include Japanese encephalitis virus and Kunjin virus.11 The latter shares 80% of its genome with WNV and has been classified as a subtype of WNV.12 It is endemic in northern tropical regions of Australia,13 and the usual presentation is as a febrile illness; it is a rare cause of encephalitis.11 There have been no reports of locally acquired flavivirus in Melbourne, Victoria, where our patient resided while in Australia.

Infection with WNV was diagnosed retrospectively in our patient based on serological testing of acute and convalescent sera. WNV IgM concentration was then measured in a stored CSF sample. The initial low-positive serological results for flavivirus group IgG suggested the patient had previously been infected with another member of the flavivirus family. The fourfold rise in IgG titre and new detection of IgM antibodies to WNV indicated this presentation was a new infection. The strongest reaction was to the New York 99 strain of WNV, which is closely related to strains isolated in Israel. Reactions to the Sarafend strain of WNV and the closely related Kunjin virus were significantly weaker. Negative PCR results are common in WNV infection because of the low-level transient viraemia of WNV.8 Similarly, only about 30% of patients have abnormal MRI findings.8

Our patient’s presentation illustrates the common clinical features of encephalitis. Fever, headache, personality change or delirium and altered conscious state are typical, and focal neurological deficits and seizures may also occur.14 The onset can be gradual. In this case, encephalitis was diagnosed on Day 9 of the illness. Initially, headache and dizziness were attributed to systemic infection until further neurological symptoms became apparent. The CSF findings were also typical of encephalitis, with an elevated white cell count and protein concentration, and glucose concentration in the reference range.14 The likelihood of WNV causing encephalitis rather than an isolated febrile illness or meningitis increases with advanced age.9

From a public health perspective, this case raises the question of whether WNV could be introduced into Australia. Culex mosquitoes are distributed widely throughout the country, and recent research has confirmed that Australian Culex mosquitoes can be infected with, and transmit, the North American strain of WNV.15 However, because of the similarity between WNV and Kunjin virus, antibodies to the latter in vertebrate hosts may limit the infectivity and establishment of WNV in the Australian environment, depending on the geographic distribution of Kunjin virus.16 The type of animal harbouring, and thus importing, WNV is also important. Some research shows humans are likely to be “dead end hosts”, with a level of viraemia that is too low to transmit to an uninfected mosquito.17 This suggests the risk of secondary cases from our patient was very low. The inadvertent or illegal importation of infected mosquitoes or birds would pose a far greater risk of introducing WNV into Australia.

- 1. Smithburn KC, Hughes TP, Burke AW, Paul JH. A neurotropic virus isolated from the blood of a native of Uganda. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1940; 20: 471-492.

- 2. Hubalek Z, Halouzka J. West Nile fever — a reemerging mosquito-borne viral disease in Europe. Emerg Infect Dis 1999; 5: 643-650.

- 3. Solomon T, Ooi MH, Beasley DW, et al. West Nile encephalitis. BMJ 2003; 326: 865-869.

- 4. Weaver SC, Barrett AD. Transmission cycles, host range, evolution and emergence of arboviral disease. Nat Rev Microbiol 2004; 2: 789-801.

- 5. Tsai TF, Popovici F, Cernescu C, et al. West Nile encephalitis epidemic in southeastern Romania. Lancet 1998; 352: 767-771.

- 6. Lanciotti RS, Roehrig JT, Deubel V, et al. Origin of the West Nile virus responsible for an outbreak of encephalitis in the northeastern United States. Science 1999; 286: 2333-2337.

- 7. Weinberger M, Pitlik SD, Gandacu D, et al. West Nile fever outbreak, Israel, 2000: epidemiologic aspects. Emerg Infect Dis 2001; 7: 686-691.

- 8. Campbell GL, Marfin AA, Lanciotti RS, et al. West Nile virus. Lancet Infect Dis 2002; 2: 519-529.

- 9. Sejvar JJ, Haddad MB, Tierney BC, et al. Neurologic manifestations and outcome of West Nile virus infection. JAMA 2003; 290: 511-515.

- 10. Mackenzie JS, Broom AK, Hall RA, et al. Arboviruses in the Australian region, 1990 to 1998. Commun Dis Intell 1998; 22: 93-100.

- 11. McCormack JG, Allworth AM. Emerging viral infections in Australia. Med J Aust 2002; 177: 45-49. <MJA full text>

- 12. Coia G, Parker MD, Speight G, et al. Nucleotide and complete amino acid sequences of Kunjin virus: definitive gene order and characteristics of the virus-specified proteins. J Gen Virol 1988; 69 Pt 1: 1-21.

- 13. Mackenzie JS, Lindsay MD, Coelen RJ, et al. Arboviruses causing human disease in the Australasian zoogeographic region. Arch Virol 1994; 136: 447-467.

- 14. Mandell GL, Dolin R, Bennett JE, et al. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s principles and practice of infectious diseases. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone, 2005.

- 15. Jansen CC, Webb CE, Northill JA, et al. Vector competence of Australian mosquito species for a North American strain of West Nile virus. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2008; 8: 805-811.

- 16. Mackenzie JS, Smith DW, Hall RA. West Nile virus: is there a message for Australia [editorial]? Med J Aust 2003; 178: 5-6. <MJA full text>

- 17. Hayes EB, Komar N, Nasci RS, et al. Epidemiology and transmission dynamics of West Nile virus disease. Emerg Infect Dis 2005; 11: 1167-1173.

We thank Associate Professor Denis Spelman (Alfred Hospital, Melbourne) for his comments on this manuscript.

None identified.