Oral white lesions are a common clinical finding; in a recent study of more than 17 000 people in the United States, these lesions were found in 27.9%.1 The lesions represent a wide spectrum of diagnoses of varying seriousness, ranging from traumatic keratosis to dysplasia and squamous cell carcinoma. Although there are classical features associated with each diagnosis, appearances overlap, complicating diagnosis. As patients with oral white lesions often present first to general practitioners, it is important for GPs to be familiar with the differential diagnoses, and to have a high index of suspicion to ensure appropriate investigation and referral. Examples of potential diagnostic dilemmas are shown in Box 1.

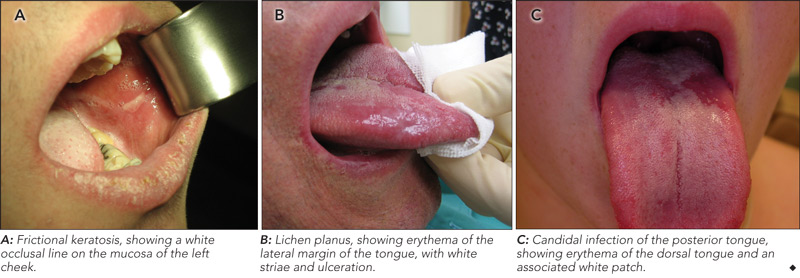

On examination, the location, and surface and subepithelial characteristics of lesions are important factors in diagnosis2,3 (see diagnostic algorithm, Box 2). White lesions in high-risk areas, such as the ventral surface of the tongue and floor of the mouth, have a high propensity for neoplastic change. Surface debris that is easily wiped off suggests candidiasis, while a speckled white patch that cannot be rubbed off is potentially precancerous, carcinoma in situ or squamous cell carcinoma. A homogeneous, striated white patch with no evidence of surface breach is likely to be benign (Box 3 A). Lesions may have a warty surface (Box 1 A). Verrucoid-papillary leukoplakia (verrucous hyperplasia), characterised by an irregular exophytic wart-like appearance, has been reported to be premalignant and has the potential to spread locally.4 Lesions may show temporal progression. Early leukoplakia presents as a faint, slightly elevated white plaque, but it can progress to a thicker and whiter lesion with development of a leathery appearance and fissuring surface.

Leukoplakia is a clinical term traditionally used to describe an oral white lesion that cannot be rubbed off or characterised as any other definable lesion.5 More recently, it was redefined as a predominantly white lesion with premalignant potential.6 It is the most common clinical diagnosis of oral white lesions,7 but does not have a histological basis. Lesions with surface irregularities are referred to as granular or nodular leukoplakia, and those with papillary surfaces as verrucous leukoplakia.8

Because of its premalignant potential, leukoplakia should be treated with caution. Reports indicate that 17%–25% of cases of leukoplakia transform to dysplasia, carcinoma in situ or carcinoma.9,10 Malignant transformation is reported to occur in 3%–17.5% of cases.11

Clinical features that suggest malignant transformation include speckled red–white appearance, induration, rolled edge, fixation to underlying structures and rapid growth. A significantly greater proportion of speckled lesions (9.1%) than homogeneous leukoplakia (1.3%) undergo malignant transformation,12 and the risk of developing malignancy in erosive leukoplakia (including the erythematous component) is reported to be fivefold higher than for other forms of leukoplakia.13

A common clinical feature of oral lichen planus is a bilateral white reticulated pattern on the buccal mucosa or lateral part of the tongue, and erosive or atrophic lesions may also be present (Box 3 B). Biopsy is important to rule out conditions that may resemble oral lichen planus clinically, including lupus erythematosus, dysplasia and squamous cell carcinoma. A small percentage of oral lichen planus lesions (1%) are reported to undergo malignant transformation.14

Oral lichen planus lesions can be controlled by topical steroids in combination with management of any underlying or associated conditions. Regular review is important to assess the effectiveness of therapy and to diagnose malignant transformation early.14,15

Oral candidal lesions often have specific characteristics at initial examination, including white plaque that can be removed to reveal an erythematous base (Box 3 C). In the chronic form of candidiasis, the mucosal surface is bright red and smooth. When the tongue is involved, it may appear dry, fissured or cracked. Patients may report a dry mouth, burning pain and difficulty eating.3 Almost 50% of healthy individuals carry Candida albicans, and infection can be confirmed with a smear stained with periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) to detect candidal hyphae.

Chronic hyperplastic candidiasis (or candidal leukoplakia) commonly presents as a tough plaque that cannot be rubbed off in the postcommissural buccal mucosa or dorsum of tongue. It is distinguishable from other types of leukoplakia only through examination of an incisional biopsy specimen. Gram and PAS staining show candidal hyphae embedded in clumps of detached epithelial cells. This type of lesion has increased propensity for dysplastic change and warrants close monitoring.16

Use of antifungal creams and lozenges, as well as improved oral hygiene, will often lead to resolution of oral candidiasis symptoms. Any associated underlying conditions, such as diabetes, should also be managed.17

Oral mucosal squamous cell carcinoma accounts for most oral cancers.18 It has a high propensity for metastasis, and is associated with high morbidity and mortality. Hence, early detection is crucial for a good outcome.

Oral mucosal squamous cell carcinoma may appear clinically as a painless ulcer, classically non-healing, indurated, and erythematous, with a white rolled border.19 It may also appear as a speckled red–white patch, with induration, a rolled edge and rapid growth. Invasion of adjacent structures — with sensory loss, muscle tethering, sinus blockage and persistent epistaxis — suggests malignancy. A fungating ulcer with indurated border suggests an advanced lesion. Advanced malignancy is also associated with systemic manifestations, such as hoarseness of voice, a sensation of something in the throat, and difficulty with speech and swallowing.19 Extraoral palpation should include the neck, especially along the superficial and deep jugular lymph node chain, where metastasis is commonly found. Palpation of pre-auricular and parotid lymph nodes is also important.19

- Kai H Lee

- Ajith D Polonowita2

- Christchurch Hospital, Christchurch, New Zealand.

None identified.

- 1. Schulman JD, Beach MM, Rivera-Hidalgo F. The prevalence of oral mucosal lesions in U.S. adults: data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. J Am Dent Assoc 2004; 135: 1279-1286.

- 2. Soukos N. Oral leukoplakia, idiopathic. Emedicine. Omaha, Neb: Medscape, 2008. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/853864-overview (accessed Jan 2009).

- 3. Knight J. Diagnosing oral mucosal lesions. Physician Assist 2003; 27: 34-43.

- 4. Silverman S, Gorsky M, Lozada F. Oral leukoplakia and malignant transformation: a follow-up study of 257 patients. Cancer 1984; 53: 563-568.

- 5. Kramer IR, Lucas RB, Pindborg JJ, Sobin LH. Definition of leukoplakia and related lesions: an aid to studies on oral precancer. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1978; 46: 518-539.

- 6. Axell T, Pindborg JJ, Smith CJ, van der Waal I. Oral lesions with special reference to precancerous and tobacco-related lesions: conclusions of an international symposium held in Uppsala, Sweden, May 18–21, 1994. International Collaborative Group on Oral White Lesions. India: Mosby Year Book Inc, 1998: 128.

- 7. Bouquot JE. Common oral lesion found during a mass screening examination. J Am Dent Assoc 1986; 112: 50-57.

- 8. Neville BW, Day TA. Oral cancer and precancerous lesions. CA Cancer J Clin 2002; 52: 195-215.

- 9. Bouquot IE, Gorlin RJ. Leukoplakia, lichen planus and other oral keratoses in 23,616 white Americans over the age of 35 years. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1986; 61: 373-381.

- 10. Waldron CA, Shafer WG. Leukoplakia revisited: a clinicopathologic study of 3256 oral leukoplakias. Cancer 1975; 36: 1386-1392.

- 11. Sciubba JJ. Oral leukoplakia. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 1995; 6: 147-160.

- 12. Roed-Petersen B. Cancer development in oral leukoplakia: follow-up of 331 patients [abstract]. J Dent Res 1971; 50: 711.

- 13. Banoczy J. Follow-up studies in oral leukoplakia. J Maxillofac Surg 1977; 5: 69-75.

- 14. Lodi G, Scully C, Carrozzo M, et al. Current controversies in oral lichen planus: report of an international consensus meeting. Part 2. Clinical management and malignant transformation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2005; 100: 164-178.

- 15. Al-Hashimi I, Schifter M, Lockhart PB. Oral lichen planus and oral lichenoid lesions: diagnostic and therapeutic considerations. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2007; 103 Suppl 1: S25.e1-S25.e12.

- 16. Sitheeque MAM, LP Samaranayake. Chronic hyperplastic candidosis/candidiasis (candidal leukoplakia). Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 2003; 14: 253-267.

- 17. Scully C, Porter S. ABC of oral health: swellings and red, white, and pigmented lesions. BMJ 2000; 321: 225-228.

- 18. Wingo PA, Tong T, Bolden S. Cancer statistics, 1995. CA Cancer J Clin 1995; 45: 8-30.

- 19. Weinberg MA, Estefan DJ. Assessing oral malignancies. Am Fam Physician 2002; 65: 1379-1384.

Abstract

General practitioners are often the first point of contact for patients with oral white lesions, which represent a wide spectrum of diagnoses of varying seriousness.

Some clinical features are classical and others overlap between different diagnoses; they should be correlated with patient history, and sometimes other investigations, for diagnosis.

Leukoplakia is a clinical term, and is a diagnosis of exclusion with no histopathological connotation. It has been redefined to describe a predominantly white lesion with premalignant potential.

Patients with lesions that are potentially malignant should be referred to an oral medicine specialist or oral maxillofacial surgeon for systematic management.