Clinical records

The patient was initially treated for strongyloides infection with ivermectin, but the eosinophilia persisted. Diethylcarbamazine (150 mg three times daily) was given for 14 days. Within 2 weeks, the eosinophil count had dropped to 1.0 × 109/L. The patient was clinically well at follow-up 3 months later.

Tropical pulmonary eosinophilia is a rare but well recognised syndrome characterised by pulmonary interstitial infiltrates and marked peripheral eosinophilia. We report three cases of this syndrome presenting with cough in immigrants to Australia, to highlight awareness of this treatable infectious disease. This condition is more widely recognised and promptly diagnosed in filariasis-endemic regions, such as the Indian subcontinent, Africa, Asia and South America. In non-endemic countries, patients are commonly thought to have bronchial asthma.1,2 Chronic symptoms may delay the diagnosis by up to 5 years.1 Early recognition and treatment with the antifilarial drug, diethylcarbamazine, is important, as delay before treatment may lead to progressive interstitial fibrosis and irreversible impairment.3

Lessons from practice

Tropical pulmonary eosinophilia should be considered in patients who have lived in filaria-endemic countries, such as the Indian subcontinent, and present with respiratory symptoms and hypereosinophilia.

The most common misdiagnosis is asthma, with overlapping symptoms of chronic cough, paroxysmal dyspnoea and wheeze.

Early diagnosis and treatment with diethylcarbamazine (DEC) may prevent progressive pulmonary disease.

The condition of marked eosinophilia with pulmonary involvement was first termed tropical pulmonary eosinophilia in 1950.4 The syndrome is caused by a distinct hypersensitivity immunological reaction to microfilariae of W. bancrofti and Brugia malayi.3,5 However, only a small percentage (< 0.5%)6 of the 130 million people globally who are infected with filariasis apparently develop this reaction. The clearance of rapidly opsonised microfilariae from the bloodstream results in a hypersensitive immunological process and abnormal recruitment of eosinophils, as reflected by extremely high IgE levels of over 1000 kU/L.3,7 The typical patient is a young adult man from the Indian subcontinent.5

The diagnostic criteria for tropical pulmonary eosinophilia7 include:

history supportive of exposure to lymphatic filariasis;

peripheral eosinophilia count (> 3 × 109/L);

elevated serum IgE levels (> 1000 kU/L);

increased titres of antifilarial antibodies;

peripheral blood negative for microfilariae; and

clinical response to diethylcarbamazine.

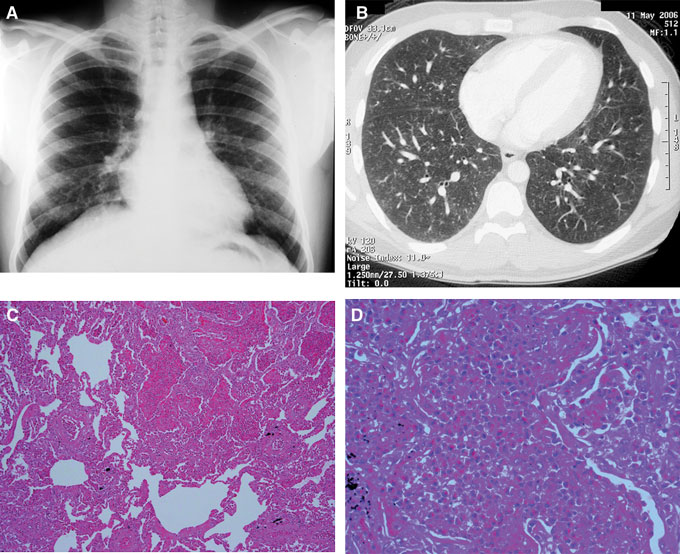

High antifilarial IgG titres to microfilariae often result in cross reactivity with other non-filarial helminth antigens,8,9 such as strongyloides and schistosoma antigens, as demonstrated in our reported cases. It is important to exclude other parasitic infections before tropical pulmonary eosinophilia is diagnosed, by serological tests, examination of stool specimens in a laboratory experienced in parasitic infections, or a trial of antihelminth medication. Other parasitic infections, such as the zoonotic filariae, dirofilariasis, ascariasis, strongyloides, visceral larva migrans and hookworm disease, may also be confused with tropical pulmonary eosinophilia because of overlapping clinical features, serological profile and response to diethylcarbamazine3,7,9,10 (Box 1). Radiological findings are non-specific, with normal appearance on chest x-ray in up to 20%.5 Although lung biopsy was performed in Patient 2, it is not part of the routine diagnostic work-up of tropical pulmonary eosinophilia.

No universal treatment guidelines have been established for tropical pulmonary eosinophilia.1,7 The antifilarial diethylcarbamazine (6 mg/kg/day for 21 days6) remains the main therapeutic agent and is generally well tolerated. Reported side effects include headache, fever, pruritis and gastrointestinal upset.11 The eosinophil count often falls dramatically within 7–10 days of starting treatment.3 Diethylcarbamazine is available only through the Special Access Scheme of the Therapeutic Goods Administration. Symptoms persist after treatment in up to 25% of patients.5 The role of adjunctive therapy with corticosteroids in preventing long-term fibrosis has not been studied.

- 1. Boggild AK, Keystone JS, Kain KC. Tropical pulmonary eosinophilia: a case series in a setting of nonendemicity. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 39: 1123-1128.

- 2. Jiva TI, Poe RH. Tropical pulmonary eosinophilia masquerading as acute bronchial asthma. Respiration 1996; 63: 55-58.

- 3. Ong R, Doyle R. Tropical pulmonary eosinophilia. Chest 1998; 113: 1673-1679.

- 4. Ball J, Treu R. Tropical pulmonary eosinophilia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1950; 44: 237-258.

- 5. Udwaida F. Tropical eosinophilia. In: Herzog H, editor. Pulmonary eosinophilia: progress in respiration research. Basel, Switzerland: Karger, 1975; 7: 35-155.

- 6. World Health Organization. Lymphatic filariasis: the disease and its control. Fifth report of the WHO Expert Committee on Filariasis. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 1992; 821: 1-71.

- 7. Ottesen EA, Nutman TB. Tropical pulmonary eosinophilia. Annu Rev Med 1992; 43: 417-424.

- 8. Muck AE, Pires ML, Lammie PJ. Influence of infection with non-filarial helminths on the specificity of serological assays for antifilarial immunoglobulin G4. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2003; 97: 88-90.

- 9. Magnaval JF, Berry A. Tropical pulmonary eosinophilia. Clin Infect Dis 2005; 40: 635-636.

- 10. Kuzucu A. Parasitic diseases of the respiratory tract. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2006; 12: 212-221.

- 11. McLaughlin SI, Radday J, Michel MC, et al. Frequency, severity and costs of adverse reactions following mass treatment for lymphatic filariasis using diethlycarbamazine and albendazole in Leogane, Haiti 2000. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2003; 68: 568-573.

We thank Dr Malcolm Buchanan, Consultant Pathologist, Royal Melbourne Hospital, for providing the lung biopsy images. Caroline Marshall receives support from the Clinical Centre for Research Excellence in Infectious Diseases, University of Melbourne, VIC.