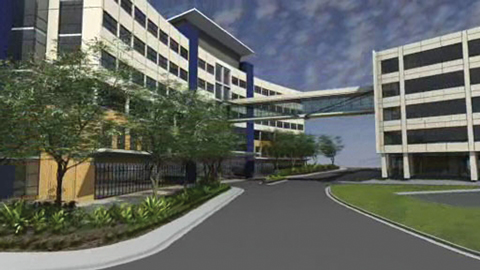

The Australian School of Advanced Medicine has been established at Macquarie University, Sydney, to provide university-based programs for medical specialists. The school will be based at a new state-of-the-art hospital (Macquarie University Private Hospital), construction of which is about to start (see Box).

The education programs, at specialist and subspecialist levels, will be for medical practitioners who wish to acquire a documented set of professional competencies at a university rather than in the traditional service environment. However, the programs will be rigorously practical and competency-based: for example, surgeons will spend 3 days a week on clinical work, and will be summatively assessed on consistent achievement of a set of clearly defined surgical and professional competencies. Eligibility to graduate will be based on assessment of the trainee’s contribution to the work of the team responsible for health care,1,2 rather than on the traditional criteria of largely academic examinations, and time spent in training.

At the specialist (College Fellowship) level, some current training programs and examinations may not be a sound basis for lifelong learning and continuous quality improvement, given their teacher-centredness and the common lack of constructive alignment between learning objectives, learning activities and examinations.3 It has been argued that professional competence, rather than time served, should be the criterion for success.4

The second theme is comprehensive competence. Scholars will develop a high level of technical competence in their specialist or subspecialist fields, as well as demonstrated competence in generic areas, such as ethical and professional clinical practice and the practice of education and research.5 Scholars will be expected to be reflective about their experiences and their practice, and will be required to commit these reflections to paper for exploration. Support from mentors will be provided for this, and for all the Scholars’ learning activities.

The third theme is teamwork. Good patient outcomes arise from the coordinated actions of all members of the clinical team, medical and non-medical, and not just from the expertise of one clinician.6 There will be an emphasis on conscious exploration and analysis of team function and how it can be maintained and improved, both in terms of patient outcomes and as a learning environment.

The personalised nature of the learning environment will mean that Advanced Scholars will have to distribute some of their time to Scholars’ and their own education. Advanced Scholars will be well known, sought-after leaders in their own fields, but will also acknowledge their own need to continue learning. The effect of the Scholar on the Advanced Scholar’s learning is as relevant to the learning process as the obverse.2

The work-based assessment system will ensure validity (“measuring what we want to measure”) and positive educational impact (“Scholars learning what we want them to learn”), but to develop assessments that are reliable and free from personal bias will require careful planning and meticulous implementation and evaluation.7,8

A question frequently raised with us is the ethical propriety of using private patients in training programs. We believe that close supervision by Advanced Scholars will minimise risk to patients, and there is evidence that patient outcomes are no worse with the active participation of supervised specialist trainees.9 Trainees in general practice have, for many years, undertaken minor procedures on private patients under supervision. It is unethical not to inform patients about what we propose. Patient care is a team effort, and patients should be told that they are entrusting their care to a cohesive and efficient team, rather than to a single individual.

- Rufus Clarke1

- Michael K Morgan

- 1 Australian School of Advanced Medicine, Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW.

- 2 Macquarie Neurosurgery, Sydney, NSW.

None identified.

- 1. Brown JS, Collins A, Duguid P. Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educ Researcher 1989; 18: 32.

- 2. Davis B, Sumara DJ. Cognition, complexity, and teacher education. Harvard Educ Rev 1997; 67: 105-125.

- 3. Biggs JB. Teaching for quality learning at university. 2nd ed. Maidenhead: SRHE and Open University Press, 2003.

- 4. Morgan MK, Clarke RM, Lyon PMA, et al. The neurosurgical training curriculum in Australia and New Zealand is changing. Why? J Clin Neurosci 2005; 12: 115-118.

- 5. Hays RB, Davies HA, Beard JD, et al. Selecting performance assessment methods for experienced physicians. Med Educ 2002; 36: 910-917.

- 6. Soni D, Morgan MK. Surgical education in the 21st century [authors’ response to editorial]. J Neurosurg 2007; 106: 959-960.

- 7. Morgan MK, Clarke RM, Weidmann M, et al. How assessment drives learning in neurosurgical higher training. J Clin Neurosci 2007; 14: 349-354.

- 8. Finucane PM, Barron SR, Davies HA, et al. Towards an acceptance of performance assessment. Med Educ 2002; 36: 959-964.

- 9. Morgan MK, Davidson A, Assaad NN. How does the participation of the training registrar in surgery for small intracranial aneurysms impact on patient outcome? J Neurosurg 2007; 106: 961-964.

Abstract

The Australian School of Advanced Medicine at Macquarie University, Sydney, will provide competency-based university medical specialist training in a private hospital environment.

The rationale is the need for additional and innovative programs to meet emerging demands, and alternative training programs to increase the opportunities for doctors to achieve their career goals.

The programs will focus on learning (not teaching), on developing a comprehensive set of professional competencies, on teamwork, and on research.

Special features of the programs include: the potential for scholars to progress at a variable pace; the use of facilities for simulation and practice; and rigorous evaluation.

The school is developing strong linkages with other institutions, nationally and internationally.

Challenges include the recruitment of fee-paying trainees; the time commitment required of faculty members; a reliable and bias-free assessment system; and ethical concerns about undertaking training activities on private patients.