In April 2000, a team at Hôpital Necker-Enfants Malades in Paris reported the successful use of gene therapy to treat two infants with the X-linked form of severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID-X1).1 SCID-X1 is caused by mutations in the gene encoding the common γ chain (γc) of several interleukin receptors.2,3 Affected infants typically lack both T and natural killer (NK) cells, and have normal or raised levels of functionally deficient B cells that are unable to undergo immunoglobulin class-switching and antibody production.4,5

The treatment of choice for SCID-X1, with greater than 90% survival, is bone marrow transplantation from an HLA-identical sibling donor. However, most infants lack such a donor and conventionally undergo an HLA-mismatched transplant with associated mortality rates of up to 30%.6,7 In most infants, immunological reconstitution remains incomplete, particularly B-cell function, with resultant lifelong requirement for immunoglobulin replacement therapy. Gene therapy offers these infants the potential for improved survival rates and more complete immunological reconstitution.

In collaboration with the French team, we treated an infant with SCID-X1 by gene therapy at The Children’s Hospital at Westmead, Sydney, NSW, in March 2002. Here we report the outcome.

A 6-month old male infant, the first child of non-consanguineous parents, was referred to The Children’s Hospital at Westmead with persistent pneumonia not responding to antibiotic therapy. Past history revealed an episode of cervical lymphadenitis treated with antibiotics at the age of 2 weeks and poor weight gain from 3 months. There was a strong family history of male deaths in infancy on the maternal side. Examination on presentation revealed a malnourished infant whose weight was below the 3rd centile. He had severe oral and napkin-area thrush despite topical antifungal treatment, intermittent diarrhoea, a moist cough, but no visible tonsils or palpable lymph nodes.

Chest x-ray revealed diffuse interstitial changes and an absent thymic shadow. Pneumocystis carinii was detected on bronchoalveolar lavage. Rotavirus was isolated from his stools. Immunological investigations confirmed a severe combined immunodeficiency with a complete absence of T cells and a total lymphocyte count of 2 × 109/L (reference range [RR], 2–13 × 109/L), of which 70% were B cells and 30% NK cells (RRs, 13%–35% and 2%–13%, respectively) by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis (see glossary in Box 1). Serum IgG and IgA were undetectable, while the IgM level (0.63 g/L) was in the reference range. Cell surface expression of γc was undetectable on NK cells. These NK cells (defined as CD3 -CD16/CD56+ cells) were not fully functional, exhibiting normal cytolytic activity against an NK-sensitive cell line (human chronic myeloid leukaemia cell line K562), but failure to proliferate in response to interleukin-2 (not shown).

A provisional diagnosis was made of SCID-X1 with an NK+ phenotype (a less common variant of SCID-X1). The infant was treated with high-dose intravenous trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, intravenous immunoglobulin, fluconazole and nasogastric feeding. His clinical condition improved rapidly.

Molecular studies confirmed the diagnosis. The entire genomic sequence of the γc gene was analysed after amplification of peripheral blood DNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). This revealed a single substitution (A→C) at the third base of intron 3, consistent with a splice-site mutation. Two aberrantly spliced species of γc mRNA and trace amounts of correctly spliced γc mRNA were detected by reverse transcriptase-PCR analysis, thereby unequivocally establishing the diagnosis of SCID-X1.8

As the infant did not have an HLA-compatible sibling or matched related donor, he was considered a candidate for gene therapy.

The trial proposal was evaluated by the Gene and Related Therapies Research Advisory Panel (GTRAP) of the National Health and Medical Research Council and the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) through the Clinical Trial Exemption scheme for experimental therapeutic goods. After approval by the institutional ethics committee of The Children’s Hospital at Westmead and informed parental consent, the infant was enrolled in February 2002.

We used the gene therapy protocol and standard operating procedures of the French team1,9 (Box 2). Bone marrow (143 mL) was harvested from the infant and, after selection, yielded 42.0 × 106 CD34+ cells at 79% purity (CD34+ cells are haemopoietic progenitor cells capable of differentiating into all haemopoietic lineages, including T cells.) These cells were negative for γc expression by FACS analysis.

The cells were cultured and subjected to genetic modification by a retrovirus vector encoding human γc (Box 2).1,9 The vector was derived from a replication-defective Moloney murine leukaemia virus, as previously described.10 The vector-containing supernatant was free of replication-competent retrovirus.

After genetic modification, a total of 86.2 × 106 cells were re-infused into the infant via a central line. Of these cells, 37% remained CD34+, and 10% both CD34+ and γc+ (equivalent to 1.3 × 106 CD34+/γc+ cells/kg).

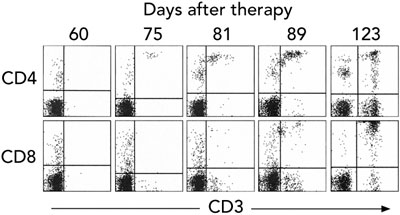

Gene therapy was performed in March 2002 when the infant was aged 9 months. Fourteen days after infusion, the earliest time-point investigated, vector-encoded γc mRNA transcripts were detected in peripheral blood cell mRNA, while integrated vector DNA was first detected at 32 days (Box 3A). These signals intensified with time, indicating replication of gene-corrected cells encoding γc. T cells (initially CD4+ cells) were first observed at 75 days (Box 3B). T-cell counts increased rapidly to 5 months, reaching 0.46 × 109 CD3+ cells/L at 154 days (Box 4).

Within 2 weeks of the appearance of T cells, there was a distinct clinical improvement, including weight gain and clearance of the chronic gastrointestinal rotavirus infection.

T cells expressing cell surface γc became detectable in the peripheral blood 3 months after treatment, and the level of γc expression on these cells increased with time (Box 5A). Analysis of peripheral blood revealed the presence of αβ (95%) and γδ (5%) T cells, naïve (CD45RA+) and memory (CD45RO+) T-cell phenotypes (not shown), and the acquisition of a diverse, albeit less complex than normal, T-cell receptor repertoire. PCR-based analysis of T-cell receptor diversity among αβ T cells revealed expression of all 28 Vβ families (Box 5B) and normal distribution of variable region length in some, but not all, families (Box 5C).

These results confirm the appearance of major lymphocyte subsets, and the ability of these cells to acquire a memory phenotype as a consequence of antigen exposure. However, the reduced complexity of the T-cell receptor repertoire suggested a reduced capacity to respond to a diverse spectrum of antigens. In addition, although T cell count increased rapidly to 5 months after therapy, there was no consistent increase in the ensuing months, and counts never reached the reference range (Box 4).

The infant had detectable but reduced levels of T-cell proliferation to mitogen when tested 4 months after gene therapy using concanavalin A, and again at 1 year using phytohaemagglutinin. There was no in-vitro T-cell proliferation response to Candida antigen at 4 months, possibly explained by lack of exposure to this infectious agent. Expression of γc on NK cells was not observed until 19 months after treatment.

The lack of detectable γc expression on B cells was unchanged, and the patient remained immunoglobulin-dependent. T-cell receptor excision circles12 (which are generated by rearrangement of the T-cell receptor locus and provide a measure of naïve T-cell production) remained undetectable in samples of peripheral blood taken 4, 8 and 16 months after treatment (not shown). The apparent discrepancy between the detection of naïve T cells and failure to detect T-cell receptor excision circles might be explained by low numbers of cells undergoing T-cell receptor rearrangement, followed by higher than normal levels of replicative expansion.

To date, 18 infants worldwide have been treated for SCID-X1 by gene therapy: 10 in France, seven in Britain (unpublished observations), and our patient. Seventeen remain alive and, with a single exception, have undergone partial or complete immunological reconstitution.

Our patient underwent partial immunological reconstitution after gene therapy. Initially, T-cell counts increased rapidly, as observed in other infants,1,9,13 reaching near maximal levels about 5 months after treatment, but they never reached the reference range. The T-cell receptor repertoire, while diverse, did not attain normal levels of complexity, T-cell responsiveness remained impaired, and the infant continued to be dependent on intravenous immunoglobulin. We hypothesise that this partial immune reconstitution was most likely due to the relatively low dose of CD34+/γc+ gene-corrected cells reinfused (1.3 × 106 cells/kg). Infants undergoing robust immunological reconstitution have received higher cell doses, in the range 3 × 106–22 × 106 cells/kg.9

Another factor possibly affecting immune reconstitution was the viral infection that occurred 4 months after gene therapy. However, a contrary argument is the good immune reconstitution seen in two infants in the French series who had severe viral infections at the time of gene therapy (unpublished observations, A F, M C-C and S H-B-A).

Finally, the infant’s NK+ phenotype might have had an effect, possibly by reducing the selective growth advantage of genetically corrected T-cell progenitors in the bone marrow. This selective advantage is believed to underpin the success of gene therapy in SCID-X1.1 More data from infants with NK+ SCID is required to resolve this question. Interestingly, expression of γc on a small proportion of NK cells was first detected 19 months after treatment, a result consistent with reduced selective advantage of gene-corrected NK cells.

While clear clinical benefit initially accompanied the appearance of T cells, as evidenced by weight gain and clearance of a chronic rotavirus infection, the infant’s ongoing clinical course was complicated by the development of spastic diplegia, persistent gut dysfunction and failure to thrive. Reasons for these complications remain unclear despite extensive investigation. The neurological signs appeared in concert with rising T-cell counts, raising the possibility of an autoimmune mechanism. It is plausible that the partial immunological reconstitution led to reduced regulatory complexity in the T-cell compartment and a propensity for autoimmunity. However, an autoimmune phenomenon in the gut was not supported by histological examination of the small bowel, and enteropathy secondary to inadequate immune reconstitution was considered probable.14

Following these outcomes, therapeutic options included repeating the gene therapy procedure to “top up” the number of gene-corrected haemopoietic progenitors in the bone marrow, or bone-marrow transplantation from a matched unrelated donor. We chose the second, more conservative, action. Considerations included the possible impact of the infant’s NK+ phenotype on the efficacy of gene therapy, the unexplained neurological complications, and unresolved questions about the risk of insertional mutagenesis.

An inherent property of retroviral vectors, fundamental to their successful use in the treatment of SCID-X11,9 and, more recently, adenosine deaminase deficiency (ADA-SCID),15 is the capacity to insert copies of the encoded therapeutic gene into host-cell chromosomal DNA. Integration ensures that all cells arising from gene-modified progenitors carry the therapeutic gene. However, the downside of integration is the potential to dysregulate the expression of genes at or near the site of insertion, a process known as insertional mutagenesis.

This risk was considered largely theoretical until the recent occurrence of acute T-cell leukaemia in three of the 11 infants (including our patient) treated for SCID-X1 by gene therapy in the French-based trial. In the first two of these infants, one of whom has died,16 this was shown to be the direct consequence of retroviral vector integration into, and activation of, the oncogene LMO-2,17 which is recognised to have aberrant expression in a subset of T-cell leukaemias.18,19 The cause of leukaemia in the third infant is yet to be determined, but is likely to be similar.

Consequently, the French trial is on hold while the risk of insertional mutagenesis is re-evaluated, and strategies are developed to reduce the risk. These will involve improved design of the gene-transfer vector, more precise characterisation of target haemopoietic progenitor cells, improved culture conditions to maintain differentiation potential, and determination of the minimal cell dose required for complete immunological reconstitution. Once this is achieved, the promising efficacy of gene therapy for SCID-X1 can be further investigated. In the interim, longer term follow-up data in children already successfully treated by this approach will become available, providing further insight into therapeutic safety and durability.

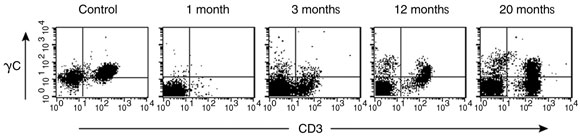

5 Characterisation of T cells in peripheral blood after gene therapy

A. Detection of cell surface γc protein expression on T cells in peripheral blood by fluorescence-activated cell sorting. The first panel shows blood from a normal control patient with T (CD3+) cells expressing γc in the upper right quadrant. Such cells were absent from our patient’s blood 1 month after gene therapy, but appeared progressively from 3 months.

B. Profile of T-cell receptor Vβ families (subsets of the β chain) present among αβ T cells in peripheral blood 18 months after gene therapy, determined by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis.11

C. Diversity of T-cell receptor repertoire within representative Vβ families, determined by PCR-based analysis at 3, 12 and 20 months after gene therapy. Panels show increasing diversity over time in the Vβ19 family, but not the Vβ28 family.

Received 26 November 2004, accepted 8 March 2005

- Samantha L Ginn1

- Julie A Curtin2

- Christine M Smyth3

- Margot Latham4

- Sharon C Cunningham5

- Maolin Zheng6

- Linda Hobson7

- Peter B Rowe8

- Ian E Alexander9

- Belinda Kramer10

- Melanie Wong11

- Alyson Kakakios12

- Geoffrey B McCowage13

- Debbie Watson14

- Stephen I Alexander15

- Alain Fischer16

- Marina Cavazzana-Calvo17

- Salima Hacein-Bey-Abina18

- 1 Gene Therapy Research Unit, The Children’s Hospital at Westmead and Children’s Medical Research Unit, Sydney, NSW.

- 2 Oncology Research Unit, The Children’s Hospital at Westmead, Sydney, NSW.

- 3 Department of Immunology and Infectious Diseases, The Children’s Hospital at Westmead, Sydney, NSW.

- 4 Department of Oncology, The Children’s Hospital at Westmead, Sydney, NSW.

- 5 Centre for Kidney Research, The Children’s Hospital at Westmead, Sydney, NSW.

- 6 Hôpital Necker, Paris, Cedex, France.

We are indebted to the patient’s family for their support of this study and are grateful to Genopoietic (Lyon, France) for supplying the vector-containing supernatant. Analysis of T-cell proliferation, NK cell cytolytic function and T-cell receptor excision circles were kindly performed by the Clinical Immunology Laboratory at the Royal Price Alfred Hospital, Sydney, NSW. We would also like to acknowledge funding from the NSW Health Department. S L G is supported by the Noel Dowling Research Fellowship.

None identified.

- 1. Cavazzana-Calvo M, Hacein-Bey S, de Saint Basile G, et al. Gene therapy of human severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID)-X1 disease. Science 2000; 288: 669-672.

- 2. Sugamura K, Asao H, Kondo M, et al. The common gamma-chain for multiple cytokine receptors. Adv Immunol 1995; 59: 225-277.

- 3. Asao H, Okuyama C, Kumaki S, et al. Cutting edge: the common gamma-chain is an indispensable subunit of the IL-21 receptor complex. J Immunol 2001; 167: 1-5.

- 4. Buckley RH, Schiff RI, Schiff SE, et al. Human severe combined immunodeficiency: genetic, phenotypic, and functional diversity in one hundred eight infants. J Pediatr 1997; 130: 378-387.

- 5. Noguchi M, Yi H, Rosenblatt HM, et al. Interleukin-2 receptor gamma chain mutation results in X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency in humans. Cell 1993; 73: 147-157.

- 6. Buckley RH, Schiff SE, Schiff RI, et al. Hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for the treatment of severe combined immunodeficiency. N Engl J Med 1999; 340: 508-516.

- 7. Antoine C, Muller S, Cant A, et al. Long-term survival and transplantation of haemopoietic stem cells for immunodeficiencies: report of the European experience 1968-99. Lancet 2003; 361: 553-560.

- 8. Ginn SL, Smyth C, Wong M, et al. A novel splice-site mutation in the gene for the common gamma chain results in severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID-X1) with an NK+ phenotype. Hum Mutat 2004; 23: 522-523.

- 9. Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Le Deist F, Carlier F, et al. Sustained correction of X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency by ex vivo gene therapy. N Engl J Med 2002; 346: 1185-1193.

- 10. Hacein-Bey S, Cavazzana-Calvo M, Le Deist F, et al. γc gene transfer into SCID X1 patients’ B-cell lines restores normal high-affinity interleukin-2 receptor expression and function. Blood 1996; 87: 3108-3116.

- 11. Walters G, Alexander SI. T cell receptor BV repertoires using real time PCR: a comparison of SYBR green and a dual-labelled HuTrecTM fluorescent probe. J Immunol Methods 2004; 294: 43-52.

- 12. Hochberg EP, Chillemi AC, Wu CJ, et al. Quantitation of T-cell neogenesis in vivo after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation in adults. Blood 2001; 98: 1116-1121.

- 13. Gaspar HB, Parsley KL, Howe S, et al. Gene therapy of X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency by use of a pseudotyped gammaretroviral vector. Lancet 2004; 364: 2181-2187.

- 14. Rotterdam H, Tsang P. Gastrointestinal disease in the immunocompromised patient. Hum Pathol 1994; 25: 1123-1140.

- 15. Aiuti A, Vai S, Mortellaro A, et al. Immune reconstitution in ADA-SCID after PBL gene therapy and discontinuation of enzyme replacement. Nat Med 2002; 8: 423-425.

- 16. Cavazzana-Calvo M, Lagresle C, Hacein-Bey-Abina S, et al. Gene therapy for severe combined immunodeficiency. Annu Rev Med 2005; 56: 585-602.

- 17. Hacein-Bey-Abina S, von Kalle C, Schmidt M, et al. LMO2-associated clonal T cell proliferation in two patients after gene therapy for SCID-X1. Science 2003; 302: 415-419.

- 18. Rabbitts TH, Bucher K, Chung G, et al. The effect of chromosomal translocations in acute leukemias: the LMO2 paradigm in transcription and development. Cancer Res 1999; 59: 1794s-1798s.

- 19. Ferrando AA, Neuberg DS, Staunton J, et al. Gene expression signatures define novel oncogenic pathways in T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Cell 2002; 1: 75-87.

Abstract

Objective: To report the outcome of gene therapy in an infant with X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID-X1), which typically causes a lack of T and natural killer (NK) cells.

Design and setting: Ex-vivo culture and gene transfer procedures were performed at The Children’s Hospital at Westmead, Sydney, NSW, in March 2002. Follow-up to March 2005 (36 months) is available.

Patient: A 9-month-old male infant with confirmed SCID-X1 (including complete absence of T cells) with an NK+ phenotype (a less common variant of SCID-X1), and no HLA-identical sibling donor available for conventional bone marrow transplantation.

Procedure: CD34+ haemopoietic progenitor cells were isolated from harvested bone marrow and cultured with cytokines to stimulate cellular replication. Cells were then genetically modified by exposure to a retrovirus vector encoding human γc (the common γ chain of several interleukin receptors; mutations affecting the γc gene cause SCID-X1). Gene-modified cells (equivalent to 1.3 × 106 CD34+/γc+ cells/kg) were returned to the infant via a central line.Results: T cells were observed in peripheral blood 75 days after treatment, and levels increased rapidly to 0.46 × 109 CD3+ cells/L at 5 months. Within 2 weeks of the appearance of T cells, there was a distinct clinical improvement, with early weight gain and clearance of rotavirus from the gut. However, T-cell levels did not reach the reference range, and immune reconstitution remained incomplete. The infant failed to thrive and developed weakness, hypertonia and hyperreflexia in the legs, possibly the result of immune dysregulation. He went on to receive a bone marrow transplant from a matched unrelated donor 26 months after gene therapy.

Conclusions: This is the first occasion that gene therapy has been used to treat a genetic disease in Australia. Only partial immunological reconstitution was achieved, most likely because of the relatively low dose of gene-corrected CD34+ cells re-infused, although viral infection during the early phase of T-cell reconstitution and the infant’s NK+ phenotype may also have exerted an effect.