Vulval symptoms are common and cause considerable distress.1 In a community-based sample of 303 women in the United States, about one in five reported a history of lower genital tract discomfort that had persisted for more than three months, and one in 10 had current symptoms. 1 Two-thirds of those with discomfort reported knife-like pain or excessive pain on contact to the genital area, and one-third reported persistent itching or burning. Not only are symptoms common, they are also often chronic and can substantially interfere with sexual function.1 Correct diagnosis and treatment in general practice should reduce morbidity. Treatment often requires a considerable commitment by both the patient and practitioner, but is usually successful.

Despite the frequency of vulval symptoms, women often find it difficult to obtain expert medical advice.1 Postgraduate training for general practitioners is not widely available, and special clinics for vulval conditions have long waiting lists. Here, we outline a pragmatic approach to management of chronic vulval symptoms. Some useful websites for practitioners and patients are listed in Box 1.

The history may be difficult to elicit because of anxiety about the diagnosis, frustration about ineffective treatment, secondary sexual dysfunction or resultant and often under-recognised depression.2 When itch is the predominant symptom (with or without pain), the key feature is whether the condition is intermittent or constant. If symptoms are worse before or during menses, then recurrent vulval vaginal candidiasis is likely.3 Dermatitis can also be intermittent, with flares associated with precipitating factors.

A thorough examination with adequate lighting is essential, as changes can be subtle. The key clinical distinction is between women whose appearance on examination is essentially normal and those with clear abnormalities. Assessing pelvic floor muscle tone is necessary if penetration is painful, and attempting to elicit pain in the vestibular area with a cotton bud is useful for women with a history consistent with vulvar vestibular syndrome.4

Key features of the history and examination that are useful in diagnosing vulval conditions are shown in Box 2. For example, a young woman presenting with localised pain in the vestibular area that is provoked only by penetration and has no abnormalities on examination is likely to have vulvar vestibular syndrome (VVS). In contrast, an older woman with poorly localised pain that is not provoked and appears normal on examination may have dysaesthetic vulvodynia. Pain may take the form of burning, stinging, rawness, or severe knife-like pain.

It is important to establish realistic expectations at the beginning, as vulval conditions commonly respond slowly to treatment, usually over weeks to months. The aims of therapy are to control symptoms rather than to cure the condition. A multidisciplinary approach may be needed, as may referral to other healthcare professionals, such as physiotherapists with experience in biofeedback (use of vaginal surface electromyography, digital palpation or dilators to teach voluntary control of pelvic floor muscles) for secondary vaginismus, or sexual counsellors. Specific treatments are outlined below, but the principles of good vulval skin care should be part of the treatment of all conditions (Box 3). Women whose symptoms are not responding to treatment after two months, or who have vulval intraepithelial neoplasia or erosive vulvovaginitis, should be referred to a gynaecologist.

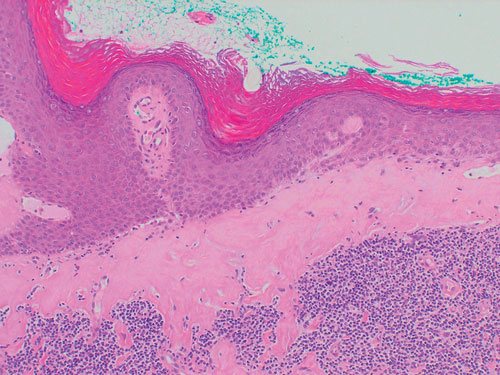

The term dermatitis describes a poorly demarcated erythematous, itchy rash (Box 5) that is characterised histologically by spongiosis.5 Subtypes include atopic, seborrhoeic, irritant, allergic and corticosteroid-induced dermatitis, and lichen simplex chronicus.5 Dermatitis is common and was present in 54% of women presenting with chronic vulval symptoms to an Australian dermatology practice.6 It is more common in individuals with atopy, whose skin is less able to tolerate environmental insults. Contact allergens have been identified in 5% to 26% of women diagnosed with vulval dermatitis, commonly medications.6,7

Itch is a common presenting symptom, although burning can occur if the mucosa is involved.6,8 Clinical signs may be subtle and include poorly defined erythema, scale, fissures, lichenification and excoriation.

Common causes of irritation are outlined in Box 4 and should be carefully sought. Ongoing avoidance of irritants and minimisation of incontinence are important in controlling symptoms.9 Therapy should begin with a potent topical corticosteroid (eg, methylprednisolone aceponate) until symptoms have resolved (E1)10 (for an explanation of level-of-evidence codes, see Box 6). At this point, a weaker corticosteroid, such as 1% hydrocortisone, can be continued for a further two to three months. This cycle can be repeated if disease activity flares. Drugs with antihistamine and sedative properties, such as doxepin (10–20 mg at night), can be helpful in controlling nocturnal scratching (E4).12

Vulvovaginal candidiasis is considered recurrent when at least four discrete documented episodes occur in one year, or at least three in one year that are not related to antibiotic therapy.13 The condition is common; in one random community sample, one in 12 women reported four or more episodes in the previous year.14 The pathophysiology of recurrent infection is unclear, but appears to involve an abnormality in the host–microorganism relationship.3,15

Recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis presents primarily with itch, but burning, especially after intercourse, is also common.3 It is characteristic for these symptoms to flare in the week before menses and to improve with the onset of menstruation. Clinical appearance is often not helpful in making the diagnosis.3 Vulval erythema, subtle swelling and occasionally longitudinal fissures may be seen, but the vaginal discharge of acute candidiasis is uncommon.3 Microscopy of low vaginal swabs for hyphae is negative in up to 50% of women with culture-positive symptomatic vulvovaginal candidiasis.3 Candida albicans is also present in up to 20% of asymptomatic women of childbearing age.3 Most cases are caused by C. albicans, but the species C. glabrata, C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis also occur and may be relatively resistant to treatment.3

About 90% of uncomplicated cases of vulvovaginal candidiasis respond to oral or topical antifungals, although a secondary irritant contact dermatitis from topical imidazoles may occur (E2).8,16,17 Data from non-randomised clinical trials support longer treatment (14 days) for recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis, followed by a maintenance regimen for six months (E3).8,16 Some recommended maintenance regimens include clotrimazole (500 mg vaginal suppositories weekly), oral ketoconazole (100 mg daily), oral fluconazole (100–150 mg weekly) and oral itraconazole (400 mg monthly or 100 mg daily).16,17 Compliance is better with oral therapy, which also avoids the irritation of topical treatments.3,8 An estimated one in 10 000–15 000 persons exposed to ketoconazole may develop hepatotoxicity.16 If there is a significant dermatitic reaction, 1% hydrocortisone ointment is useful, at least in the early stages. About 70% of women with C. glabrata or other non-albicans species respond to intravaginal boric acid (600 mg daily in a gelatin capsule for 14 days [E3]).16,17 Topical flucytosine (4%) has also been used (E3).16,17

Treatment strategies for which there is little or no evidence include dietary modification (eg, sugar-free diet), antifungal treatment to eliminate Candida spp. from the gastrointestinal tract,18,19 and treatment of asymptomatic male sexual partners for Candida spp.20,21 Combined pills can be continued as long as the oestrogen dose is low (20–30 μg ethinyloestradiol), and occasionally progesterone-only contraception may be tried (E4).22

Lichen sclerosus was found in 13% of 141 women presenting to an Australian dermatology practice with chronic vulval symptoms.6 It is an idiopathic inflammatory skin disease that has a predilection for the genital skin. It has been linked to a several autoimmune diseases, including Grave's disease and vitiligo.23

Lichen sclerosus most commonly presents with pronounced itch, although burning and dyspareunia can also occur.24 It may occur anywhere over the vulval, perineal or perianal skin and is uncommon at extragenital sites.24 The vagina is not involved. Typically, it presents with well defined white plaques and an atrophic, wrinkled surface (Box 7). There may also be purpura, hyperpigmentation, erosions, fissures and oedema.24 Longstanding disease may result in labial shrinking, obliteration of the clitoral hood and occasionally restriction of the introitus, resulting in difficult and painful intercourse.24

The diagnosis should be confirmed by skin biopsy (Box 7). Treatment should aim to control symptoms, minimise scarring and detect malignant change early. Potent topical corticosteroids are symptomatically effective in over 90% of women, providing rapid symptomatic relief and variable objective improvement (E4).25 Betamethasone dipropionate ointment (0.05%) is used initially twice daily for a month, then daily for two months, and gradually tapered to use as needed (ideally only once or twice per week). Annual follow-up is recommended, as longitudinal studies suggest that the lifetime risk of squamous-cell carcinoma within the affected area is about 4%.26

Psoriasis is less common than lichen sclerosus and was present in only 5% of women presenting to a dermatologist with chronic vulval symptoms.6 It can be easily mistaken for atopic dermatitis, but clues include a family history of psoriasis and evidence of psoriatic lesions elsewhere on the skin (scalp, natal cleft or nails). Clinically, psoriasis on the vulva may lack scale, but it tends to be more symmetrical, erythematous and well defined than dermatitis.

Psoriasis often requires more aggressive and prolonged treatment than dermatitis. Weaker-potency corticosteroids, such as 1% hydrocortisone, are often insufficient for maintenance, and a stronger corticosteroid, such as betamethasone valerate (0.02% twice daily), is often needed27 (E2). Weak tar preparations, such as 3% liquor picis carbonis in aqueous cream twice daily, is an alternative to provide a break from continuous corticosteroid use27 (E2).

In a series of 69 Australian cases, vulval intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) was diagnosed in only 7% of women in a gynaecology practice and none of those in a dermatology practice.9 The most common symptoms are localised itch and burning, although two-thirds of cases are asymptomatic.28 VIN usually appears as multifocal plaques that are raised on keratinised skin or macules on mucosal areas. VIN3 (severe neoplasia or carcinoma-in-situ) can progress to invasive cancer, but the rate at which this occurs is controversial.28 Cases of VIN should be referred for further assessment to a gynaecological oncologist.

Oestrogen deficiency causes the vaginal epithelium to become thin, pale and dry.29 Symptoms include superficial dyspareunia, minor vaginal bleeding and pain from splitting caused by friction.29 Topical vaginal oestrogen creams are beneficial (E4).29 Oestriol cream or pessaries are used daily for three weeks and then once or twice a week for maintenance.

Vulvar vestibular syndrome (VVS) is also known as vestibulitis, vestibulodynia, vestibular pain syndrome and localised vulval dysaesthesia. Its exact prevalence is difficult to estimate, but studies suggest it may be more common than is recognised. Among 210 women attending a US gynaecological practice, 15% fulfilled the criteria for VVS, and 38% had some clinical features.30 In a community-based survey, 12% of 303 women reported a history of knife-like or excessive pain on contact to the genital area that would be consistent with the syndrome.1 At the specialised vulval clinic at Melbourne Sexual Health Centre, VVS was diagnosed in 30% of 159 consecutive clients seen in 1997–1998 (unpublished data).

Altered pain perception is the major feature of this syndrome.31,32 The typical patient is a nulliparous woman in her 20s or early 30s who often develops symptoms suddenly. The pain is characterised by extreme tenderness to pressure within the vulvar vestibule. Pain with attempted vaginal entry is the most common complaint. In the absence of localised pressure, women are symptom-free. It may follow a precipitating inflammatory condition or occur spontaneously.4 With time, this sensitivity to pressure or stretch may preclude intercourse or the insertion of tampons. Pain characteristically may improve after initial penetration. Many women have associated urinary symptoms (frequency and bladder irritability) in the absence of infection, which have raised suggestions that this syndrome is associated with interstitial cystitis.33 This may be explained by the shared embryological development, and therefore innervation, of the bladder and vestibule from the urogenital sinus.

Physical signs are restricted to exquisite tenderness in the region of the posterior (and less commonly the anterior) vestibule. Gentle pressure with a cotton swab commonly elicits pain.

Management is often difficult and prolonged and involves both behavioural and medical interventions that are common to many pain syndromes.34 Coexisting disease (such as candidiasis) should be excluded, and irritants avoided (E4). Sympathy and strong positive reassurance are required, and sexual counselling should be offered. A number of treatments have been tried, including xylocaine gel 30 minutes before intercourse and pelvic floor retraining with biofeedback, as vaginismus is common (E3).35 Low-dose tricyclic antidepressants, such as amitriptyline 10–75 mg at night, may be helpful in some patients (E4),36 and newer agents for neuropathic pain show promise (E4).37 In cases that do not respond to medical treatment, surgery (forms of vestibulectomy) may offer relief (E4),38 but is rarely performed in Australia.

Dysaesthetic vulvodynia (also known as essential vulvodynia and generalised vulval dysaesthesia) occurs mainly in older patients. The predominant symptom is chronic, poorly localised vulval burning or pain.39 No abnormalities are found on examination, but there may be diffuse and variable hypersensitivity and altered perception to light touch. The exact aetiology is unclear, but the condition shares some features with neuropathic pain syndromes (eg, poor localisation, persistence after removal of the noxious stimulus, little response to routine analgesia, and often a burning quality). Referred pain from the back or pelvis and recurrent herpes simplex should be excluded. If the description of the pain is bizarre or inconsistent, psychogenic pain should be considered but is rare.

Low-dose tricyclic antidepressants (eg, amitriptyline, 10–75 mg at night) is the standard treatment for dysaesthetic vulvodynia (E4).39 Gabapentin,37 desipramine, imipramine40 and venlafaxine41 have also been reported as beneficial (E4).

1: Useful websites for clinicians and clients

International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (www.issvd.org)

National Vulvodynia Association (www.nva.org)

Melbourne Sexual Health Centre (www.mshc.org.au)

Vulval Pain Society (www.vul-pain.dircon.co.uk)

National Lichen Sclerosus Support Group (www.lichensclerosus.org)

3: Initial skin management for women with vulval pain or itching

Avoid irritants (Box 4).

Moisturise dry skin with creams such as Sorbolene or aqueous cream (these are often more soothing if kept refrigerated).

Use barrier creams, such as zinc and castor oil cream or Vaseline, if there is incontinence or vaginal discharge.

Reduce scratching as much as possible by applying cold compresses.

Application of potassium permanganate solution (1: 8000) 2–3 times daily for 3–5 days is often helpful.

Ensure there is adequate arousal and use lubricants for limited sexual intercourse; vegetable oils are less irritant than water-based lubricants.

4: Common vulval irritants

Body fluids: sweat, vaginal secretions,* urine and semen.

Hygiene products: soaps, gels, bath oils, bubble bath, douches, perfumes,† deodorants,† depilatory creams and sanitary pads.†

Medicaments: disinfectants,† tea tree oil,† preservatives in creams,† antifungal creams,† topical anaesthetics† and topical antibacterial agents.†

Lubricants and contraceptives: spermicides,† condoms† and diaphragms.†

Physical items: sanitary pads and tampon strings, tight clothing, synthetic underwear, toilet paper, overzealous cleansing and scrubbing, shaving and plucking of hair.

* Including abnormal vaginal discharge requiring treatment. † Some chemicals may also cause true allergic contact dermatitis.

5: Dermatitis of the vulva

Dermatitis, showing poorly defined erythema extending beyond the flexures with excoriations.

6: Level-of-evidence codes

Evidence for the statements made in this article is graded according to a modification of the NHMRC system for assessing the level of evidence.11

E1 Level I: Evidence obtained from a systematic review of all relevant randomised controlled trials.

E2 Level II: Evidence obtained from at least one well designed randomised controlled trial.

E3 Level III: Evidence obtained from at least one non-randomised controlled trial, cohort or case–control studies.

E4 Level IV: Evidence obtained from case series, either post-test, or pre-test and post-test.

- 1. Harlow BL, Wise LA, Stewart EG. Prevalence and predictors of chronic lower genital tract discomfort. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2001; 185: 545-550.

- 2. Heim LJ. Evaluation and differential diagnosis of dyspareunia. Am Fam Phys 2001; 63: 1535-1544.

- 3. Sobel JD. Vulvovaginitis. Dermatol Clin 1992; 10: 339-359.

- 4. Metts JF. Vulvodynia and vulvar vestibulitis: challenges in diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician 1999; 59: 1547-1556, 1561-1562.

- 5. Marren P, Wojnarowska F, Powell S. Allergic contact dermatitis and vulvar dermatoses. Br J Dermatol 1992; 126: 52-56.

- 6. Fischer GO. The commonest causes of symptomatic vulvar disease: a dermatologist's perspective. Aust J Dermatol 1996; 37: 12-18.

- 7. Crone AM, Stewart EJ, Wojnarowska F, et al. Aetiological factors in vulvar dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2000; 14: 181-186.

- 8. Marren P, Wojnarowska F. Dermatitis of the vulva. Semin Dermatol 1996; 15: 36-41.

- 9. Fischer G, Spurrett B, Fischer A. The chronically symptomatic vulva: aetiology and management. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1995; 102: 773-779.

- 10. Hoare C, Li Wan Po A, Williams H. Systematic review of treatments for atopic eczema. Health Technol Assess (Winch Eng) 2000; 4: 1-191.

- 11. National Health and Medical Research Council. A guide to the development, implementation and evaluation of clinical practice guidelines. Canberra: NHMRC, AusInfo, 1999.

- 12. Gupta MA, Guptat AK. The use of antidepressant drugs in dermatology. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2001; 15: 512-518.

- 13. Ringdhal EN. Treatment for recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. Am Fam Physician 2000; 61: 3306-3312.

- 14. Foxman B, Barlow R, D'Arcy H, et al. Candida vaginitis. Sex Transm Dis 2000; 27: 230-235.

- 15. Ferrer J. Vaginal candidosis: epidemiological and etiological factors. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2000; 71: S21-S27.

- 16. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines 2002. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep 2002; 51 (RR-6): 1-78.

- 17. Rex JH, Walsh TJ, Sobel JD, et al. Practice guidelines for the treatment of candidiasis. Clin Infect Dis 2000; 30: 662-678.

- 18. Horowitz BJ, Giaquinta D. Evolving pathogens in vulvovaginal candidiasis: implications for patient care. J Clin Pharmacol 1992; 32: 248-255.

- 19. Lacour M, Zunder T, Huber R, et al. The pathogenetic significance of intestinal Candida colonization — a systematic review from an interdisciplinary and environmental medical point of view. Int J Hyg Environ Health 2002; 205: 257-268.

- 20. Fong IW. The value of treating the sexual partners of women with recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis with ketoconazole. Genitourin Med 1992; 68: 174-176.

- 21. Denning DW. Management of genital candidiasis. BMJ 1995; 310: 1241-1244.

- 22. Dennerstein G. Depo Provera in the treatment of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. J Reprod Med 1986; 31: 801-803.

- 23. Meyrick Thomas RH, Ridley CM, McGibbon DH, et al. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus and autoimmunity — a study of 350 women. Br J Dermatol 1988; 118: 41-46.

- 24. Ball SB, Wojnarowska F. Vulvar dermatoses: lichen sclerosus, lichen planus, and vulval dermatitis/lichen simplex chronicus. Semin Cutan Med Surg 1998; 17: 182-188.

- 25. Sinha P, Sorinola O, Luesley DM. Lichen sclerosus of the vulva. Long-term steroid maintenance therapy. J Reprod Med 1999; 44: 621-624.

- 26. Wallace HJ. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Trans St Johns Hosp Dermatol Soc 1971; 57: 9-30.

- 27. Ashcroft DM, Po AL, Williams HC, et al. Systematic review of comparative efficacy and tolerability of calcipotriol in treating chronic plaque psoriasis. BMJ 2000; 320: 963-967.

- 28. Kaufman RH. Intraepithelial neoplasia of the vulva. Gynecol Oncol 1995; 56: 8-21.

- 29. Detre T, Hayashi TT, Archer DF. Management of the menopause. Ann Int Med 1978; 88: 373-378.

- 30. Goetsch MF. Vulvar vestibulitis: prevalence and historic features in a general gynecologic practice population. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1991; 164: 1609-1614; discussion, 1614-116.

- 31. Meana M, Binik YM, Khalife S, et al. Dyspareunia: sexual dysfunction or pain syndrome? J Nerv Ment Dis 1997; 185: 561-569.

- 32. Masheb RM, Nash JM, Brondolo E, et al. Vulvodynia: an introduction and critical review of a chronic pain condition. Pain 2000; 86: 3-10.

- 33. Fitzpatrick CC, DeLancey JOL, Elkins TE, et al. Vulvar vestibulitis and interstitial cystitis: A disorder of urogenital sinus-derived epithelium? Obstet Gynecol 1993; 81: 860-862.

- 34. Bergeron S, Binik YM, Khalife S, et al. Vulvar vestibulitis syndrome: reliability of diagnosis and evaluation of current diagnostic criteria. Obstet Gynecol 2001; 98: 45-51.

- 35. Glazer HI, Rodke G, Swencionis C, et al. Treatment of vulvar vestibulitis syndrome with electromyographic biofeedback of pelvic floor musculature. J Reprod Med 1995; 40: 283-290.

- 36. Bohl TG. Vulvodynia and its differential diagnoses. Semin Cutan Med Surg 1998; 17: 189-195.

- 37. Ben-David B, Friedman M. Gabapentin therapy for vulvodynia. Anesth Analg 1999; 89: 1459-1460.

- 38. McCormack WM, Spence MR. Evaluation of the surgical treatment of vulvar vestibulitis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1999; 86: 135-138.

- 39. McKay M. Dysesthetic ("essential") vulvodynia. Treatment with amitriptyline. J Reprod Med 1993; 38: 9-13.

- 40. Davis GD, Hutchison CV. Clinical management of vulvodynia. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1999; 42: 221-233.

- 41. Eisen A. Venflaxine therapy for vulvodynia. Pain Clinic 1995; 8: 365-367.

Abstract

Community-based surveys indicate that about a fifth of women have significant vulval symptoms lasting over three months at some time in their lives.

Common causes of itch or pain are dermatitis, recurrent candidiasis and the recently recognised pain syndromes — vulvar vestibular syndrome and dysaesthetic vulvodynia.

Diagnosis is usually apparent after a thorough history and examination, although conditions commonly coexist and are complicated by prior treatment.

Skin lesions not responding to treatment require biopsy.

Treatment aims to control symptoms rather than to cure; avoiding soaps and other irritants is central to management.

An early, accurate diagnosis should enhance management of vulval conditions, particularly pain syndromes.