A substantial number of people experience medication-related problems.1,2 Australian studies1,3 have shown that closer collaboration between general practitioners and pharmacists, together with better medication review by pharmacists,2 can help to identify and resolve many of these problems.

In its 1999 Budget, the Federal Government allocated funding for the provision of Home Medication Reviews (HMRs). The Department of Health and Aged Care (now the Department of Health and Ageing) called for research proposals to establish a model for implementing these services.4 Our project aimed to design and test a collaborative model for delivering and evaluating HMRs. We report the results of an implementation trial in which we set out to determine the requirements for and outcomes of an area-wide HMR service.

We used a participatory action research design,5 in which researchers worked with participants to design, implement and evaluate the service, allowing researchers and participants to solve problems that arose as the research progressed. The participatory action research process involved general practitioners, pharmacists and consumers in a series of workshops, focus groups and feedback sessions.

A call for expressions of interest in participating in the project was sent to all Divisions of General Practice in South Australia. Eight of the 15 Divisions responded and six participated (three rural and three urban Divisions). A Divisional Liaison Officer (DLO) was employed in each Division to facilitate the interaction between GPs and pharmacists and to assist in the local implementation of the HMR service.

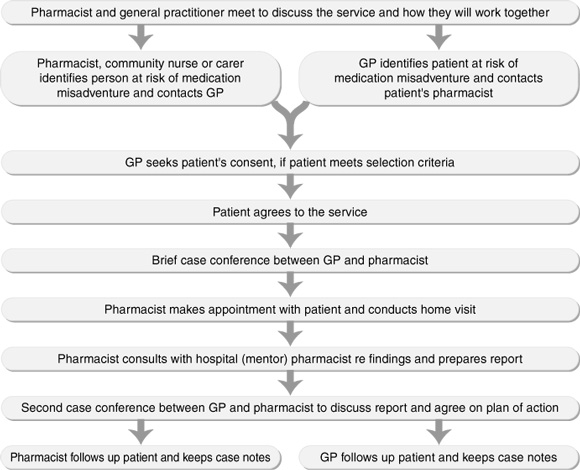

A collaborative service delivery model (Box 1) was agreed on, and standard forms for documenting relevant patient information, reports and action plans were developed in consultation with participating GPs and pharmacists.

The study was carried out between March 1999 and March 2000.

Each GP or pharmacist identified 5–10 eligible patients from their practices, based on patient selection criteria that had been previously used to identify patients at risk of having medication-related problems (Box 2). GPs were eligible for RACGP clinical audit points if 10 of their patients participated in the study.

For any patient identified by a community pharmacist, the pharmacist consulted the patient's GP to ensure the patient met eligibility criteria. Verbal consent for participation in the study was sought from each patient and recorded by the GP in the patient's case notes.

Two researchers coded the medical conditions, medications taken and medication-related problems from patient case notes. Medical conditions were categorised according to the International classification of diseases (ICD-9-CM),6 medications according to the Anatomical and therapeutic classification7 and medication-related problems according to previously employed criteria (Box 3).1,3,8 From patient case notes, the researchers noted actions taken to address the problems (Box 4) and outcomes of those actions (Box 5). For some patients, the GP and pharmacist identified more than one problem.

Pharmacists identified 2764 medication-related problems, the most common (17.5%) being the need for additional tests (Box 3). On average, 2.5 problems were identified per person.

Thirty-seven per cent of all problems related to medicine selection, 20% to patient knowledge and skills, and 17% to the medication regimen. Only 1% of problems related to drug–drug interactions, 2% to contraindicated therapy, 2% to the use of medicine without indication, and 1% to duplication of therapy.

In response to the identified problems, pharmacists recommended 2764 actions to GPs, of which 1163 (42%) were documented in patient case notes as having been implemented. No information was available on implementation of the remaining actions. This may mean that no action was taken, that the action was rejected by the GP, that follow-up had not occurred at the time of the study's completion, or that the action had been previously trialled, was still under consideration or was implemented but poorly documented. The types of actions most commonly implemented included changes to medicine selection; changes to the dose, frequency or duration of therapy; and patient education (Box 4).

Follow-up data, as recorded in the patient's case notes, were available for 978 (84%) of the problems for which an action was documented as having been implemented. Problems were documented as being "resolved" or "well managed" in 61% of these cases, and "improving" in a further 20% (Box 5). Outcome data were available for 85 of the problems for which no actions were implemented. In 61 of these cases the problem was unresolved or worse at follow-up, with only 13 of the problems resolved or well managed at follow-up.

The model required GPs and pharmacists to negotiate actions based on the pharmacist's report. In 23 instances the GP refused to implement the action(s); in 31 instances, although the GP and pharmacist agreed on the action, the patient refused.

Our study showed that a collaborative medication management service could be successfully implemented through Divisions of General Practice and was acceptable to all participants. The process employed enabled GPs and pharmacists to identify people at risk of medication misadventure and to resolve many of their medication-related problems.

Problems relating to medication use were common. Importantly, outcome data reveal that the service resulted in 81% of problems being resolved, well managed or improving at follow-up. Although the study was restricted to South Australia, the inclusion of both rural and urban Divisions improves the generalisability of the findings.

The nature and extent of medication-related problems, particularly in older at-risk people, has been well described.1,3,8 The establishment of professional relationships between GPs and pharmacists, achieved through the participatory action research approach in our study, was an important element in the success of the project.

Importantly, our model is compatible with the Enhanced Primary Care package,9 which includes case conferencing as a rebatable item.

There are many opportunities for collaboration between GPs and pharmacists to improve health outcomes for consumers. People at high risk of medication misadventure include those living in residential aged-care facilities, those with chronic illnesses (eg, mental health problems, asthma, diabetes, cardiovascular disease), and those returning home after a stay in hospital.

Based on the evidence presented in this project, the HMR service, which is currently being implemented nationally,4 has the potential to improve the overall management of medicines in the community and significantly improve health outcomes for consumers in Australia.

2: Selection criteria for patient participants1

Patients included those who were

taking multiple medications;

taking 12 or more doses of medication a day;

taking high doses of medication;

on complicated medication regimens;

taking medications requiring regular monitoring;

having difficulty with compliance;

showing signs of potential drug-induced problems or interactions;

not showing the expected response to their medication;

living alone and having a history of cognitive impairment or difficulty with vision or hearing;

recently hospitalised;

considered by a general practitioner or other medical professional as likely to benefit from the service.

3: Frequency of medication-related problems identified from patient case notes

Problem category |

Occurrence |

||||||||||

Management issues |

|||||||||||

Need for an additional test (eg, serum creatinine and electrolytes) |

483 |

(17.5%) |

|||||||||

Need for additional therapy (eg, physiotherapy, podiatry) |

142 |

(5.1%) |

|||||||||

Problems related to medicine selection |

|||||||||||

Need for additional medicine (eg, influenza vaccine, analgesics) |

321 |

(11.6%) |

|||||||||

Wrong or inappropriate medicine (eg, NSAIDs where history indicates |

319 |

(11.5%) |

|||||||||

Adverse drug reactions, including drug–drug interactions and allergies |

236 |

(8.5%) |

|||||||||

Unnecessary medicine (eg, quinine taken long-term for nocturnal leg |

153 |

(5.5%) |

|||||||||

Problems related to medication regimen |

|||||||||||

Dose too low (eg, analgesics) |

223 |

(8.1%) |

|||||||||

Dose too high (eg, psycholeptics) |

137 |

(5.0%) |

|||||||||

Rationalisation of drug therapy (eg, changing dose administration time |

97 |

(3.5%) |

|||||||||

Problems related to patient knowledge and skills |

|||||||||||

Poor understanding of disease and/or treatment |

197 |

(7.1%) |

|||||||||

Compliance problems |

138 |

(5.0%) |

|||||||||

Inappropriate technique (eg, using asthma inhalers) |

99 |

(3.6%) |

|||||||||

Lifestyle issues |

75 |

(2.7%) |

|||||||||

Anxiety about treatment |

43 |

(1.6%) |

|||||||||

Other |

|||||||||||

Medicines out-of-date |

101 |

(3.7%) |

|||||||||

Total |

2764 |

(100.0%) |

|||||||||

NSAID = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug. ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme. |

|||||||||||

4: Actions recommended and implemented to resolve medication-related problems

Action |

Number of actions |

Number of actions |

|||||||||

Change medication selection because inappropriate/wrong drug being taken |

640 |

(23.2%) |

289 |

(24.9%) |

|||||||

Consider other management options |

536 |

(19.4%) |

161 |

(13.8%) |

|||||||

Adjust dosage regimen |

532 |

(19.2%) |

233 |

(20.0%) |

|||||||

Change medication based on result of a recommended test/examination |

495 |

(17.9%) |

110 |

(9.5%) |

|||||||

Provide patient education and training |

309 |

(11.2%) |

212 |

(18.2%) |

|||||||

Assist with equipment/administration aids |

171 |

(6.2%) |

80 |

(6.9%) |

|||||||

Collect/arrange disposal of medication |

81 |

(2.9%) |

78 |

(6.7%) |

|||||||

Total |

2764 |

(100.0%) |

1163 |

(100.0%) |

|||||||

5: Outcomes after taking action to resolve medication-related problems

Outcome |

Frequency |

||||||||||

Problem resolved (clear statement given in case notes, or self-evident |

548 |

(56.0%) |

|||||||||

Problem well managed (clear statement in case notes that processes have been established to enable patient to manage an identified problem) |

48 |

(4.9%) |

|||||||||

Problem improving (case notes indicate some steps have been taken |

200 |

(20.4%) |

|||||||||

Problem unchanged (case notes indicate no change in identified problem) |

144 |

(14.7%) |

|||||||||

Problem worse (case notes indicate deterioration in patient's health) |

17 |

(1.7%) |

|||||||||

Resolution has created new problem (case notes indicate that resolution of one problem directly leads to another [eg, allergic reaction to recommended medication]) |

7 |

(0.7%) |

|||||||||

Problem being monitored (case notes indicate general practitioner is aware of problem and has agreed, as part of the plan, to monitor patient) |

14 |

(1.4%) |

|||||||||

Total |

978 |

(100.0%) |

|||||||||

- Andrew L Gilbert1

- Elizabeth E Roughead2

- Kathy Mott3

- John D Barratt4

- Justin Beilby5

- 1 Quality Use of Medicines and Pharmacy Research Centre, School of Pharmaceutical, Molecular and Biomedical Sciences, University of South Australia, Adelaide, SA.

- 2 Department of General Practice, University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA.

Our study was supported by funding from the 2nd Pharmacy/Government Agreement administered through the Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care.

None identified.

- 1. March G, Gilbert A, Roughead E, Quintrell N. Developing and evaluating a model for pharmaceutical care in Australian community pharmacies. Int J Pharm Pract 1999; 7: 220-229.

- 2. Roberts M, Stokes J, King M, et al. Outcomes of a randomised controlled trial of a clinical pharmacy intervention in 52 nursing homes. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2001; 51: 257-265.

- 3. Krass I, Smith C. Impact of medication regimen reviews performed by community pharmacists for ambulatory patients through liaison with general medical practitioners. Int J Pharm Pract 2000; 8: 111-120.

- 4. Framework document for domiciliary medication management reviews. Medication Management Implementation Steering Group, February 2001. Available at: <http://www.aacp.com.au/dmmr/frame.pdf>. Accessed 26 September 2001.

- 5. Colquhoun D, Kelleher A. Health research in practice: political, ethical and methodological issues. London: Chapman and Hall, 1993.

- 6. International classification of diseases. 9th revision. Clinical modification. (ICD-9-CM). 3rd ed. Bethesda, Md: US Department of Health and Human Services, 1989.

- 7. Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care. Australian statistics on medicines 1998. Canberra: AusInfo, 1999.

- 8. Cipolle RJ, Strand LM, Morley PC. Pharmaceutical care practice. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1998.

- 9. Primary care initiatives: enhanced primary care package. Canberra: Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care, 1999.

Abstract

Objective: To implement and evaluate a collaborative medication management service model.

Design: Participatory action research.

Setting and participants: The study was conducted from March 1999 to March 2000; 1000 patients, 63 pharmacists and 129 general practitioners from six Divisions of General Practice in South Australia participated.

Interventions: A collaborative service delivery model, involving a preliminary case conference, a home visit and a second case conference, was agreed through discussions with medical and pharmacy organisations and then implemented.

Outcome measures: Medication-related problems; actions recommended; actions implemented; and outcomes after actions taken.

Results: Overall, 2764 problems were identified. The most common medication-related problem (17.5% of all problems) was the need for additional tests. Thirty-seven per cent of problems related to medicine selection, 20% to patient knowledge, and 17% to the medication regimen. Of 2764 actions recommended to resolve medication-related problems, 42% were implemented. Of the 978 problems for which action was taken and follow-up data were available, 81% were reported to be "resolved", "well managed" or "improving".

Conclusion: This implementation model was successful in engaging GPs and pharmacists and in assisting in the resolution of medication-related problems.