The spectrum of motor vehicle accidents in the Northern Territory (NT) is unique, due in part to the absence of a speed limit outside urban areas, the relatively high use of alcohol and the vast distances travelled. Furthermore, most roads have light traffic. As a result, single-vehicle rollover (SVRO) accidents dominate the statistics. The hospitalisation and fatality rates due to motor vehicle accidents in the NT are well above those for the rest of Australia, with fatalities reaching four times the Australian average (40.1 deaths per 100 000 versus 10.8 deaths per 100 000, respectively; 1996 data).1

The significant contribution of SVROs to injury from motor vehicle accidents worldwide has been poorly recognised in the medical literature, apart from reports of rollover accidents resulting from agricultural tractors2 and all-terrain vehicles.3 The problem of vehicle rollovers has been recognised by the Commonwealth Department of Transport and Regional Services,4 with the establishment of design rules relating to such factors as the ability of a bus superstructure to withstand forces encountered in rollover crashes. Apart from these design criteria, there are limited statistics and few publications in Australia directly concerning SVRO accidents.

The aims of our study were to assess the extent of the problem of SVRO accidents in the "Top End" of the NT, identify possible contributing factors, and identify features of SVRO accidents that are associated with major injury and death.

The "Top End" of the Northern Territory is a region of more than half a million square kilometres lying to the north of the town of Elliot and including the Darwin, Katherine and East Arnhem regions (Box 1).

The Royal Darwin Hospital is a 310-bed university teaching hospital that functions as the tertiary referral centre for this region, including referrals from the Katherine and Gove hospitals. In 1996 the population of the referral area was 139 515 people, representing 77% of the NT population.5

A retrospective review of data from several sources gave us information on all motor vehicle accidents in the Top End of the NT between 1 January 1996 and 31 December 1997. We searched the Royal Darwin Hospital's trauma database and the NT Department of Transport and Works' police database. Having identified all SVRO accidents from the police database, we then reviewed all SVRO-related deaths and hospital admissions recorded by the Royal Darwin, Katherine and Gove hospitals.

Data routinely recorded on all patients admitted to the Emergency Department of the Royal Darwin Hospital include age, sex, demographic details, particulars of prehospital care undertaken by medical or paramedical staff, vital signs and primary survey findings at time of admission, any resuscitation undertaken, results of investigations in the Emergency Department, and any operations performed. Injuries are coded according the Abbreviated Injury Scale scoring system, and the Injury Severity Score is calculated from this.6 The data are entered into the database by a dedicated trauma nurse based in the Emergency Department.

From this database, we obtained data on all admissions to the Emergency Department resulting from motor vehicle accidents.

For all reported motor vehicle accidents in the NT, police officers attending the scene record the details on a traffic accident report form. These data are then stored by the NT Department of Transport and Works in a database. Data collected include the type of accident (SVRO or other) and outcome of injuries suffered (hospital admission, treatment or death). Also recorded are factors contributing to the crash, such as driver factors (eg, excessive speed, following too closely behind another vehicle, disobeying road rules), vehicle factors (eg, type of vehicle, vehicle defects, use and location of restraining devices in the vehicle), and environmental factors (eg, weather and road conditions).

Using information from the police database, we retrospectively reviewed all deaths and admissions recorded by the Royal Darwin, Katherine and Gove hospitals that resulted from SVRO in the Top End. Our review accessed hospital case notes, together with reports from coronial investigations and postmortem examinations.

Backwards stepwise logistic regression analysis, using the SPSS for Windows Advanced Statistical Package (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois), was used to identify risk factors for SVRO accidents. Data are presented as both a crude odds ratio (for each factor alone) and an adjusted odds ratio (for that factor in relation to all other factors analysed, as listed), with 95% confidence intervals. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

The project was approved by the Top End Human Research Ethics Committee and the Menzies School of Health Research, Royal Darwin Hospital.

A total of 2524 people were involved in motor vehicle accidents in the NT between January 1996 and December 1997, with 1519 (60%) suffering injury or death. The resulting incidence of hospitalisation was 240.6 per 100 000 NT population per year (not all injured people were admitted), with a fatality rate of 36.5 per 100 000 NT population per year. These rates are significantly higher than Australia-wide figures (120.2 hospitalisations and 10.8 fatalities per 100 000 population, in 19961). The most common type of accident over the period studied was the SVRO, which occurred in 30% (227/757) of all accidents and accounted for 29% (128/441) of all injuries/deaths in the NT. The breakdown of other recorded accidents in the whole of the NT over the same period is shown in Box 2.

Of the 441 people recorded in the Department of Transport and Works' police database as injured in an SVRO in the NT, 62% (273/441) were injured in accidents that occurred in the Top End. Of these, 147 were identified from hospital records as being admitted either to the emergency department or a hospital ward, or dying before reaching hospital.

In comparison with all other motor vehicle accidents in the same time period, factors identified as associated significantly more frequently with SVRO accidents were (i) occurrence of the accident on a straight, dry, unsealed road; (ii) presence of a vehicle defect; (iii) travelling at excessive speed (as assessed by investigating police officers); and (iv) wearing a seatbelt (see Box 3).

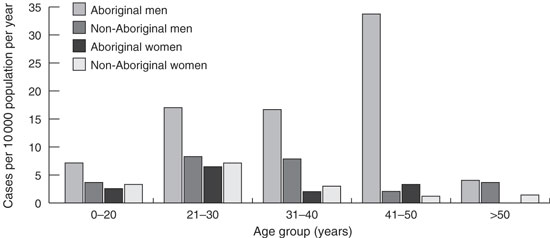

On a proportion-of-population basis, the group at highest risk of being involved in an SVRO were men aged 41–50 years of Aboriginal descent (33.7 people per 10 000 population per year; 10 persons in 8 separate accidents; odds ratio [OR] 16.3 compared with non-Aboriginal men) (see Box 4). People involved in SVRO accidents were significantly more likely to be non-NT residents than NT residents (see Box 3).

Of the 147 people identified as being admitted to hospital and/or dying as a result of an SVRO accident, 31 (21%) suffered a major injury (ie, had an Injury Severity Score > 15). People were significantly more likely to have suffered a major injury if (i) they were under the influence of alcohol (as determined by police), (ii) they were ejected from the vehicle, (iii) they were not wearing a seatbelt, (iv) the accident occurred in a rural area, and (v) the vehicle was travelling at excessive speed (as assessed by the investigating police officers using crash reconstruction techniques) (Box 5). People who died were significantly more likely to have been ejected (OR, 14.4 [95% CI, 3.75–55.2]; P = 0.0003) and under the influence of alcohol (OR, 3.13 [95% CI, 1.01–10.3]; P = 0.024).

Major injuries occurred in 21% (31/147) of people admitted overall. The most common major injuries were to the extremities (15% of those injured), head (10%), chest (8%), neck (9%), face (5%) and abdomen (7%). People who died suffered a significantly higher proportion of major injuries to the head (36% v 8%; OR, 6.83 [95% CI, 1.92–24.3]; P = 0.012), chest (29% v 6%; OR, 6.25 [95% CI, 1.60–24.4]; P = 0.0086) and neck (36% v 6%; OR, 8.68 [95% CI, 2.35–32.1]; P = 0.015). Major injuries to the face, abdomen or extremities were not significantly associated with death.

Our study shows that SVRO accidents are the main cause of morbidity and mortality from motor vehicle accidents in the Top End of the NT. SVRO accidents occur mainly on straight, dry, unsealed roads; the vehicles are often speeding and have at least one defect. It is likely that fatigue is also a major factor contributing to SVRO accidents. Although we were unable from our data to assess the contribution of fatigue, it has been estimated that 20%–30% of serious road crashes in Australia involve driver fatigue.7

On a proportion-of-population basis, the population group at greatest risk of injury due to SVRO accidents in the NT are Aboriginal men aged 41–50 years. Major injury is also more likely in accidents occurring in rural areas. Sealing of roads and injury prevention programs (such as driver education programs, provision of alternative transport, removal of road defects) targeted specifically at high-risk groups such as these might help reduce the injury toll.8

Our analysis indicated that both excessive speed and vehicle defects occurred more commonly in SVRO accidents than other accidents (Box 3), implying a causal relationship. However, it may be that vehicle defects are not related to accident causation, but rather that the vehicles involved are older vehicles, owned by members of poorer communities. We did not specifically identify such a subgroup within the data. Such an analysis might help further target specific groups at greatest risk. The assessment of excessive speed was made by the attending police officer. An assessment of exact speeds, using crash reconstruction techniques, might help identify a speed threshold above which risks are significantly increased, and thus help to devise a speed management regime for areas in which there is currently no speed limit. However, the assessment of pre-impact speed can not always be accurately calculated using conventional crash reconstruction techniques.

Our study included only motor vehicle accidents that were reported to police or that resulted in people presenting at a hospital. This may have led to bias in that some less severe accidents may not have been reported. However, we believe the bias would be minimal, as the law in the NT (and the rest of Australia) requires that all motor vehicle accidents be reported to the police within 24 hours, no matter how small.

The effectiveness of seatbelts in preventing injury has been shown in previous studies.9 In our study, the wearing of a restraining device such as a seatbelt was more common in SVRO accidents than in other types of motor vehicle accidents. A possible explanation for this may be that restraining devices are often not available in certain other types of motor vehicle accidents (eg, when people are in the rear tray of a utility, on a motorbike, or in a bus). We deliberately did not analyse data from subgroups such as accidents involving utility vehicles, as we were keen to avoid extrapolation from small subpopulations.

Unfortunately, the results of our study confirm that a large proportion of people are not wearing seatbelts, even when available (38% of all people in SVRO accidents were not wearing seatbelts), and are thus contributing to their own death and morbidity. Ongoing reinforcement of this fact is clearly necessary and has been proven beneficial in other places.9 In our study, the wearing of seatbelts was associated with a reduced incidence of major injury and death resulting from SVRO accidents. Unfortunately, data were not available to pinpoint ejection routes from the vehicle. Such data might help with the development of in-vehicle countermeasures for preventing ejection in rollover crashes.

Injuries sustained from vehicle rollover are often severe. The extent of major injuries that result from motor vehicle accidents as a whole has been well documented for Australia previously.8 In our study, death from SVROs was primarily from injury to the head, chest, or neck. While major facial injuries have recently been documented resulting from rollover injuries of all-terrain vehicles,10 in our series this was a less common site of injury and was less commonly associated with death. The high level of injury associated with vehicle rollovers has been recognised by the American College of Surgeons, which has incorporated vehicle rollover in its trauma triage criteria.11 Similarly, at the Royal Darwin Hospital, a vehicle rollover, especially if the injured person was ejected, is used as a criterion for activation of the hospital's trauma team.

3: Factors associated significantly more frequently with single-vehicle rollover accidents than non-rollover accidents in the "Top End" of the Northern Territory, January 1996 to December 1997

Rollover (n* = 757) |

MVA without rollover (n* = 1767) |

Odds ratio (95% CI) |

|||||||||||||

Crude |

Adjusted |

||||||||||||||

Straight road |

84% |

61% |

3.46 (2.78–4.31) |

2.97 (2.33–3.78) |

|||||||||||

Dry road |

93% |

90% |

1.41 (1.03–1.93) |

1.56 (1.10–2.24) |

|||||||||||

Unsealed road |

40% |

11% |

5.58 (4.52–6.88) |

4.59 (3.61–5.84) |

|||||||||||

Vehicle defect |

15% |

6% |

2.69 (2.03–3.57) |

1.72 (1.25–2.37) |

|||||||||||

Excessive speed |

16% |

8% |

2.01 (1.55–2.61) |

1.92 (1.42–2.59) |

|||||||||||

Person wearing seatbelt |

62% |

51% |

1.65 (1.38–1.96) |

2.28 (1.83–2.85) |

|||||||||||

Person of Aboriginal descent |

29% |

19% |

1.77 (1.45–2.16) |

2.24 (1.17–2.93) |

|||||||||||

Person a non-NT resident |

32% |

10% |

4.19 (3.38–5.21) |

4.21 (3.29–5.40) |

|||||||||||

MVA = motor vehicle accident. |

|||||||||||||||

4: Incidence of injury from single-vehicle rollover accidents

Graph showing incidence of injury from single-vehicle rollover accidents in the "Top End" of the Northern Territory, January 1996 to December 1997. Table shows actual numbers of people injured, by age group, sex and Aboriginal/non-Aboriginal descent.

0–20 years |

21–30 years |

31–40 years |

41–50 years |

> 50 years |

|||||||

Aboriginal men |

12 |

11 |

8 |

10 |

1 |

||||||

Non-Aboriginal men |

12 |

22 |

17 |

3 |

7 |

||||||

Aboriginal women |

4 |

4 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

||||||

Non-Aboriginal women |

10 |

14 |

6 |

2 |

2 |

||||||

5: Factors associated significantly more frequently with major injury (Injury Severity Score6 > 15) than minor injury resulting from single-vehicle rollover accidents in the "Top End" of the Northern Territory, January 1996 to December 1997

Factor |

Major injury (n* = 31) |

Minor injury (n* = 116) |

Odds ratio (95% CI) |

||||||||||||

Crude |

Adjusted |

||||||||||||||

Alcohol consumption |

48% |

23% |

2.97 (1.06–8.33) |

2.75 (1.04–7.26) |

|||||||||||

Ejection from vehicle |

67% |

18% |

9.22 (3.70–23.01) |

8.38 (3.03–23.12) |

|||||||||||

Seatbelt not worn |

73% |

44% |

3.46 (1.32–9.01) |

4.32 (1.48–12.58) |

|||||||||||

Occurring in rural area |

77% |

53% |

2.99 (1.19–7.48) |

4.71 (1.26–17.62) |

|||||||||||

Speed > 100 kph |

82% |

55% |

3.76 (1.00–14.18) |

3.78 (1.01–14.11) |

|||||||||||

*n = total number of people (drivers and passengers) who were injured. |

|||||||||||||||

Received 7 August 2001, accepted 13 February 2002

- P John Treacy1

- Kerrie Jones2

- Carole Mansfield3

- 1 Northern Territory Clinical School, Flinders University, Casuarina, NT.

- 2 Emergency Department, Royal Darwin Hospital, Darwin, NT.

The authors wish to thank Mr Ian Loftus for assistance with providing data from the NT Department of Transport and Works, Dr Didier Palmer for assistance with providing data from the Royal Darwin Hospital's Emergency Department trauma database, and Zhigiang Wang and Anne Kavanagh for statistical advice.

None declared.

- 1. Australian and New Zealand Road System and Road Authorities. National performance indicators. Sydney: Austroads, 1996.

- 2. Day LM. Farm work related fatalities among adults in Victoria, Australia: the human cost of agriculture. Accid Anal Prev 1999; 31: 153-159.

- 3. Ross RT, Stuart LK, Davis FE. All-terrain vehicle injuries in children: industry-regulated failure. Am Surg 1999; 65: 870-873.

- 4. Department of Transport and Regional Services. Land transport: the Australian design rules. 3rd ed. Canberra: Commonwealth Government, 1989.

- 5. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Population, Northern Territory. Canberra, AGPS, 1997. (Catalogue No. 3234.7.)

- 6. Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine (USA). The Abbreviated Injury Scale. 1990 revision. Des Plaines, Illinois: AAAM, 1990.

- 7. Standing Committee on Communications, Transport and the Arts. Inquiry into managing fatigue in transport. Canberra: Parliament of Australia; 2000.

- 8. Cameron P, Dziukas L, Hadj A, et al. Patterns of injury from major trauma in Victoria. Aust N Z J Surg 1995; 65: 848-852.

- 9. Clark MJ, Schmitz S, Conrad A, et al. The effects of an intervention campaign to enhance seat belt use on campus. J Am Coll Health 1999; 47: 277-280.

- 10. Marciani RD, Caldwell GT, Levine HJ. Maxillofacial injuries associated with all-terrain vehicles. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1999; 57: 119-123.

- 11. Henry MC, Hollander JE, Alicandro JM, et al. Incremental benefit of individual American College of Surgeons trauma triage criteria. Acad Emerg Med 1996; 3: 992-1000.

Abstract

Objectives: To study the incidence of and factors associated with single-vehicle rollover (SVRO) accidents in the "Top End" of the Northern Territory (NT); to identify factors associated with major injury and death from SVRO accidents.

Design: Retrospective analysis of records from the NT Department of Transport and Works' police database, Royal Darwin Hospital's trauma database, coroner's records, and case notes from public hospitals in the Top End.

Study population: All patients involved in SVRO accidents in the Top End between 1 January 1996 and 31 December 1997 whose accident was documented by the police, who attended a public hospital, or who died.

Main outcome measures: Types and incidence of all accidents; details of the accident scene, vehicle features, and population groups associated with SVRO accidents; factors associated with major injury and death.

Results: SVROs accounted for 30% of all accidents and 29% of all injuries and deaths (441 people) in the whole of the NT over the study period. Some of the factors associated significantly more frequently with SVRO accidents were (i) occurrence of the accident on a straight, dry, unsealed road; (ii) presence of a vehicle defect; (iii) travelling at excessive speed; and (iv) the person being male, aged 41–50 years, of Aboriginal descent. Among the 147 people who were admitted to hospital or died from SVRO accidents in the Top End, major injury occurred significantly more frequently if the person was under the influence of alcohol, was not wearing a seatbelt and was ejected; if the accident occurred in a rural area; and if the vehicle was speeding. Major injuries occurred in 21% (31/147), and death was more likely in those with head, chest and neck injuries.

Conclusion: SVRO accidents are a major cause of morbidity and mortality in the Top End of the NT. Effective methods of limiting speeding, drink-driving and driver fatigue should be sought. Populations most at risk should be targeted.