|

The Centenary Institute of Cancer Medicine and Cell Biology

The institute with the long name, short history, and tall goalposts Antony Basten Introduction -

The first decade: -

The second decade: -

The future: the next decade -

References -

Authors' details

|

| Introduction | As the joint centenaries of the University of Sydney's Medical School and its campus teaching hospital, Royal Prince Alfred Hospital (RPAH), crept closer in the early 1980s, a small group of clinical academics from medical, surgical, and obstetric specialties could be seen huddled together in corridors. What were they meeting about? asked their colleagues, exuding, as always, the paranoia and suspicion so common in academia. The answer soon became clear. Having trained and then exported, to other States and overseas, some of Australia's most talented researchers and clinical department heads, the time was ripe for the medical school and the hospital to reverse the New South Wales brain drain. The proposed mechanism was to be the creation on campus of a centre of excellence in medical research, akin to the successful Victorian institutes (the Walter and Eliza Hall, Baker and Howard Florey institutes) and the Garvan Institute in Sydney. |

The first decade: 1981-1989 | |

|

The idea of a centre of excellence in medical research was warmly

endorsed, not just by the university and hospital, but by the then

Federal Liberal Government and the New South Wales State Labor

Government, which jointly funded a feasibility study for

construction of a research building, to accommodate 300 staff,

adjacent to the medical school and hospital campus. In recognition of

the need for a single major centre specialising in all aspects of

cancer research and cell biology, the proposed institute received

the name it still bears under an Act of the NSW Parliament: the

Centenary Institute of Cancer Medicine and Cell Biology.1 Although

failing to fit on any conference registration form, the name was

intended to cover "all bases" -- in particular, to embody the concept

that, to understand the abnormalities responsible for disease, the

biology of normal cells must be studied first.

In 1984, an Australian Science and Technology Council (ASTEC) Working Party2 reviewed the proposal and concluded that it was far too ambitious. The Working Party's verdict was that it was better to start small and build up slowly around a competitive research group. As a result, the wind was taken out of the Centenary Institute's sails and the project was becalmed for four long years. In retrospect, it is clear that this delay worked to the Institute's disadvantage in the long term. Instead of being established before the value of the specialised research centre was fully appreciated in NSW, its creation as a functional entity coincided with the rush to institute status by multiple groups on our own campus and elsewhere, leading ultimately to the current situation, with too many "institutes" competing for limited resources. In 1989, I was invited to be the inaugural Director of the Centenary Institute. At the time, as head of the Clinical Immunology Research Centre, one of the original 10 Commonwealth Centres of Excellence, I was trying to juggle exciting new research based on transgenic technology with the task of advising the Federal Government on medical and scientific aspects of HIV/AIDS. Little did I suspect, back then, that I would be jumping out of the frying pan into the fire. | |

The second decade: 1989-1999 | |

| Early days |

The challenge in 1989 was to create an independent institute at a time

of dwindling resources, both in the tertiary education sector and in

the healthcare system. The Clinical Immunology Research Centre,

operating from its crowded quarters in the 1880 building shared with

other hospital and university staff, became the core unit of the

Institute.

We were faced with three formidable tasks. The first was to cope with the loss of our Centre of Excellence grant from the Australian Research Council, as funding for medical research centres was now deemed to be the responsibility of the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). Despite negotiating an increase in our NHMRC program grant, we were faced with an immediate loss of around $250 000 in research funding -- not the most auspicious start for a new institute. The second task was to appoint a new Board and Chairperson. A vigorous search, itself an experience for a naive academic like me, enabled us to secure the former Chairman of the Stock Exchange, Jim Bain, to chair the new Board. Under his stewardship, the Institute was steered through the next three difficult years and the Board established a Foundation, chaired by Tim Besley (Chairman of the Commonwealth Bank). The "Kick a Goal for Life" fundraising campaign, the brainchild of Ken Cowley (Chief Executive of News Ltd), a Foundation Trustee, gave us, for the first time, a public profile and much-needed funds. The campaign was launched to coincide with the final of the Commonwealth Bank Cup, awarded to the winners of the schoolboy rugby league competition. Alas, the number of on-field brawls reached such a pitch that the Commonwealth Bank promptly withdrew its support and our initial foray into the community came to an abrupt halt! The third vital task in 1989 was to obtain funding for a new building. Two further feasibility studies and six years later, four and a half floors of the Institute's new six-storey research facility were completed and fitted out at a cost of $17.24 million. This was funded largely from Federal and State capital works grants, with additional assistance from the NSW State Cancer Council and our two parent organisations, the University of Sydney and the Central Sydney Area Health Service. The Institute building is strategically located in the grounds of RPAH, adjacent to the university medical school, and was officially opened by the Prime Minister in 1997. |

| The new team | As the new edifice took shape, it was time to begin assembling a team of researchers with the skills to create a "critical mass" in immunology. My group, with its interest in self-tolerance in the B cell lineage, and that of Warwick Britton, head of a research program in mycobacterial infection, were already in place. Jon Sedgwick, well known for his work on autoimmunity in the central nervous system, was the first recruit from overseas. Described by the late Alan Williams of Oxford University as the best "postdoc" he had ever had, Jon was instrumental in grafting "knockout" (gene ablation) technology onto the Institute's existing expertise in transgenesis. Jon was followed by four other immunologists. Barbara Fazekas de St Groth, who, as a medical undergraduate, had done a BSc(Med) under my supervision a decade earlier, was the first. Returning to Sydney from postdoctoral study with Mark Davis at Stanford Medical School, Barbara is now recognised internationally for her work on tolerance and autoimmunity in T cell receptor transgenic models. Together with Patrick Bertolino, who joined us from Lyons in France two years ago, they make a formidable CD4+/CD8+ T cell team. Roland Scollay, known at the time as one of Australia's two leading exponents on thymus biology, was recruited from the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, along with Phil Hodgkin from the John Curtin School of Medical Research in Canberra. Phil's recent studies on immune regulation and the relationship between division number and lymphocyte behaviour are among the most original contributions to immunology in the past five years. The final member of the quintet was Alan Baxter, who joined us from Cambridge (UK). Alan is rapidly acquiring an excellent international reputation in the field of insulin-dependent diabetes and the genetics of autoimmune diseases, including systemic lupus erythematosus and autoimmune gastritis (see Box). |

| Achievements: the upside | |

| During the past decade, the staff has risen from 20 to 95; two NHMRC program grants have been held by research group heads; and the Institute, by virtue of its independent status, has brought to the campus more than $30 million in capital works and infrastructure funds, in addition to over $20 million in peer-reviewed grants. We were particularly delighted that Nobel laureate and immunologist, Peter Doherty, saw fit on the occasion of the official opening of the new building in 1997 to designate us as "Australia's major immunology research centre". A significant amount of the credit for these achievements must go to the Board and to Ken Tribe, its Chairman from 1994 to 1999. Ken brought to the Institute a wealth of knowledge and experience and gave us stable governance during this crucial period in our development. At the same time the work of the research staff has been underpinned by a dedicated research support and management team who have become past masters at maintaining an effective enterprise on the very shortest of shoestrings. Their loyalty and strength of purpose have been most gratifying to me personally. It has also been encouraging to work closely with the other four established independent institutes in NSW (the Garvan, Children's Medical Research, Prince of Wales Medical Research and Heart Research institutes) when negotiating with government and other bodies over issues such as infrastructure funding. | |

| The downside | |

|

If one is honest there is inevitably a downside to any enterprise

during its formative years and this has certainly applied to the

Centenary Institute. Due to the delay already alluded to in "getting

out of the blocks", the Institute has found itself competing for a

dwindling pool of resources in the era of what cynics describe as the

"epidemic of institutes". Some of them strive to be "independent"

like us, while others are "motels" for existing academic and clinical

staff or simply single departments renamed for the purpose of raising

their profile and respectability. The end-result has been ongoing

confusion among funding bodies, government, and even the community

at large about who is most deserving of support. The consequence for

the well intentioned Director and staff of the Centenary Institute

was that when the new building opened they faced a hostile reception on

campus, particularly from colleagues who were short of funds and

research space. They saw our hard-earned new building as the answer to

their prayers, while failing to appreciate our statutory charter and

independent status. If only the building had not resembled a casino!

Like all of the fledgling independent research centres which have emerged during the recent "epidemic", the Centenary Institute has had to deal with three major issues: inadequate infrastructure, limited funds for developing new groups of merit, and insufficient job security (not to mention salaries) for our full-time career scientists. Perhaps of greatest concern is the fact that the days when one can offer "fame and poverty" to the very best researchers, as Fiona Stanley so aptly put it, are dwindling fast.3 This was driven home to me when two of our most senior group heads were lured to the United States by the offer, not just of much higher salaries, but of far better resources. "If only I did not have to write so many grants for such pathetic amounts of money I would actually have time to do some research", Jon Sedgwick said to me before his departure. | |

The future: the next decade | |

| Medical research in Australia | |

|

Do institutes, independent or otherwise, have a future, or are they

likely to acquire the same mortality rate as the biotechnology

companies of yesteryear? I believe that some institutes like ours

must survive and flourish if Australian medicine is to retain its

place at the international table. We have clearly moved into the era of

specialisation, in which it is quite acceptable to be recognised as a

superb teacher or clinician or researcher, but what is no longer

feasible is to be good at every aspect of medicine. The role of

institutes, with their critical mass of full-time research staff, is

to serve as a focus for collaborative research on the campuses of

teaching hospitals and universities with which they are usually

affiliated.

It is timely that the Wills Review4 has just been published, coinciding as it does with the Federal Government's most welcome commitment to doubling NHMRC funding over the next five to six years. Not only does the Review promote competitive research by extending the concept of partnerships to both Government itself and industry, but it contains a series of innovative recipes which acknowledge the value of the independent institute as a research entity in Australia and of the full-time career scientist. Its implementation is therefore eagerly awaited, particularly by the 30-odd members of the Association of Australian Medical Research Institutes, which between them employ over 2500 research staff. In response to the Wills Review, the challenge for all of us in the medical research community is to secure sufficient ongoing funds to ensure that its recommendations bear fruit. In the case of an institute like ours, this means adding to the existing infrastructural support from the NSW State Government and the Central Sydney Area Health Service by raising funds in the non-Government sector, including from industry and the corporate and wider communities. While creating a public profile and exploiting research are anathema to the purists of the research world, the reality is that the rest of society expects to know about us if they are going to provide the financial support we urgently need. | |

| Medical research at the Centenary Institute | |

| Having commissioned a new building and recruited high-quality staff, the Institute is now poised to complete the final stage of its 10-year strategic plan. The goal is to create a second critical mass of career researchers in molecular and cellular oncology. A major step forward occurred earlier this year when a $6 million funding package was approved by the Prime Minister. The package is designed to support a strategic alliance with the Sydney Cancer Centre, whereby the Institute would develop a basic cancer research program in the remaining one and a half floors of our building to dovetail with translational and clinical research studies at the Sydney Cancer Centre, located on the adjacent RPAH campus. The first move towards this collaboration has now been made, with the conjoint appointment of John Rasko, a haematologist, who has returned to his old alma mater from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle to head up the Institute's gene therapy laboratory (see Box). The combination of our brand of cellular immunology (traditionally one of Australia's strongest disciplines) with molecular biology targeted at cancer is designed to give the Institute a discrete niche in the postgenomic era now upon us. | |

| Edward Jenner as the role model | |

|

On reading an article recently about the famous country general

practitioner, Edward Jenner,5 I rapidly perceived that he

was the ideal role model for the institute director of the future.

Jenner, famous for his discovery of smallpox vaccination, had other

admirable but lesser-known attributes, including an

entrepreneurial flair for raising funds, a fascination with diverse

areas of science, and proficiency as a poet and musician.

When the veracity of his findings on smallpox was being disputed by the inevitable envious colleagues in the United Kingdom and the United States, he raised funds from the public to extend his work (in the absence of any NHMRC equivalent). Later in his life he demanded and received special grants, the first of no less than £10 000, from the government of the day in Great Britain to compensate for the expenses incurred by his research and to set up free vaccination clinics for the public. In 1789 he was elected to the Royal Society, not for his work on vaccination, but rather for his authoritative studies on the habits of the cuckoo nestling. He also found time to classify the botanical specimens brought back by Joseph Banks from James Cook's second voyage to Australia. Despite working full-time on his research, Jenner managed to raise funds and remain a civilised human being. How wonderful it would be for those of us who are institute directors to aspire to just one or two of his many attributes. | |

| References |

|

Authors' details | |

|

Centenary Institute of Cancer Medicine and Cell Biology, Sydney,

NSW.

Antony Basten, AO, FAA, FTSE, Executive Director.

Reprints: Professor A Basten, Centenary Institute of Cancer

Medicine and Cell Biology, Locked Bag 6, Newtown, NSW 2042.

| |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

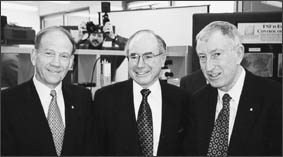

| Prime Minister John Howard (center) with Professor Peter Doherty (right) and Professor Antony Basten (left) at the offical opening of the Institute's new building in 1997. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The original headquarters of the Centenary Institute located in multipurpose building 94 at the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The new Institute building commissioned in 1994. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Received 8 February 2026, accepted 8 February 2026

- Antony Basten

- 1.

- Centenary Institute of Cancer Medicine and Cell Biology Act1985 (NSW).

- 2.

- Australian Science and Technology Council. Annual Report1983-1984. Appendix C. Canberra: AGPS, 1984: 30-36.

- 3.

- Stanley FJ. The TVW Telethon Institute for Child Health Research:the birth and growth of a research institute. Med J Aust 1998;169: 630-633.

- 4.

- Wills PJ (Chairman). Health and Medical Strategic Review. Thevirtuous cycle: working together for health and medical research.Canberra: Department of Health and Aged Care, 1999.

- 5.

- Friedman M, Friedland GW. Edward Jenner and vaccination. In:Medicine's 10 greatest discoveries. New Haven: Yale UniversityPress, 1998: 65-93.