Personal courage is most memorable when an individual shines in a time of crisis, but the quiet sacrifices of a lifetime devoted to duty are too often lost to posterity. Such seems to have been the fate of Charles Halliley Kellaway (1889–1952), who pioneered the path of independent medical research in Australia during the difficult decades after World War I.1

The close of 2007 provides good reason to reflect on Kellaway’s successes, especially as we recall the 80th anniversary of two pivotal events in Australian medical research. In 1927, the first Commonwealth grant for medical research was approved, while in 1928, a royal commission into the iatrogenic “Bundaberg tragedy” significantly heightened public appreciation of medical science. Kellaway was the central figure in both of these events, yet they formed only a small part of his contribution to Australian medical history (Box).1-14

Much of Kellaway’s character can be traced to his origins. Born in Melbourne into the family of a country clergyman, Kellaway was instilled with evangelical zeal and a lingering Victorian faith in duty and progress. While consistently topping his university courses via hard-won scholarships, Kellaway set his sights on becoming a medical missionary in India. Although he was clearly ambitious, the most enduring memory of Kellaway — recalled by all who met him — was his affability and willingness to assist others.1,15,16 These qualities were all to be tested during World War I.

Despite the prevailing imperial fervour, Kellaway’s decision to enlist was not taken lightly. He completed his postgraduate Master of Surgery and Doctor of Medicine degrees before signing up in late 1915, arriving in the Middle East just after the evacuation of Gallipoli.17 Here, he worked as a pathologist alongside the director of the Lister Institute, Charles Martin, who had undertaken pioneering research in physiology, including snake venom studies, in Australia at the turn of the century.11

In 1917, Kellaway joined the Australian Imperial Force in France as regimental medical officer for the 13th Battalion. After a battle at Zonnebeke on 26 September, he earned the Military Cross, his commanding officer noting: “During the 24 hours following the attack he worked without a moment’s respite, dealing with the wounded of five battalions in addition to his own, and at the same time controlling the work of his Stretcher Bearers. He established what must be a record by passing 400 cases through his R.A.P. [regimental aid post] in 24 hours. I cannot praise too highly his untiring devotion to duty”.17 Posted to London in 1918, Kellaway found himself working for the Royal Flying Corps and its Australian counterpart. His investigations into the physiology of anoxaemia — then a problem for military aviators — led to Kellaway’s first serious scientific research and a fortuitous association with Henry Dale, Britain’s leading pharmacologist.1,8

Although his experiences at the front converted Kellaway to agnosticism, his wartime work with Martin and Dale redirected his energies to a new calling — the betterment of humanity through medical research. After the war, these two mentors saw Kellaway appointed as a Foulerton scholar of the Royal Society. From 1920 to 1923, he undertook a tour of duty through many of the major English laboratories, mastering experimental techniques in physiology, pharmacology, immunology, biochemistry and pathology.1

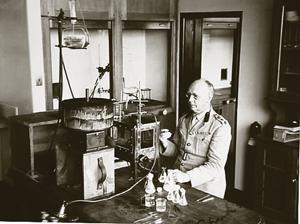

In 1923, the directorship of Melbourne’s nascent Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Research in Pathology and Medicine (as it was then known) became vacant. The WEHI at this point was the only independent centre for medical research in Australia, comprising fewer than a dozen staff and a paltry annual budget of £2500.15 Both Martin and Dale proposed Kellaway for the post, noting his superior research qualifications over those of the other candidate.15,18

The key achievements of Charles Halliley Kellaway (1889–1952)

Received 23 September 2007, accepted 29 October 2007

- Peter G Hobbins1

- Kenneth D Winkel2

- 1 Medical Humanities Unit, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW.

- 2 Australian Venom Research Unit, Department of Pharmacology, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC.

The authors thank Associate Professor Alison Bashford from the History Department at the University of Sydney for her guidance throughout the thesis research on which this article is based, and Professor Sir Gustav Nossal for advice and encouragement. We also thank all three of Charles Kellaway’s sons and several of his former colleagues, who assisted with interviews and other correspondence. The Australian Venom Research Unit gratefully acknowledges funding support from the Australian Department of Health and Ageing and the History of the University unit at the University of Melbourne. We also thank Ross Macfarlane, archive curator at the Wellcome Trust Library, London, and Dr Margaret Brumby, formerly the WEHI’s general manager, for their assistance and access to unpublished documents and archive materials. Finally, we thank Brad Allan at the WEHI for permission to reproduce photographs of Charles Kellaway.

None identified.

- 1. Dale HH. Charles Halliley Kellaway, 1889–1952. Obit Not Fellows R Soc 1953; 8: 502-521.

- 2. Butler AG. The Australian Army Medical Services in the war of 1914–1918. Volume 3. Special problems and services. Canberra: Australian War Memorial, 1930–1943.

- 3. Burnet M. Walter and Eliza Hall Institute 1915–1965. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1971.

- 4. Wood IJ. Discovery and healing in peace and war: an autobiography. Melbourne: Ian J Wood, 1984.

- 5. Brogan AH. Committed to saving lives: a history of the Commonwealth Serum Laboratories. Melbourne: Hyland House, 1990.

- 6. Hooker C. Diphtheria, immunisation and the Bundaberg tragedy: a study of public health in Australia. Health History 2000; 2: 52-78.

- 7. Kellaway CH, MacCallum P, Tebbutt AH. Report of the Royal Commission of Inquiry into fatalities at Bundaberg. Canberra: HJ Green, 1928.

- 8. Kellaway CH. Some physiological effects of anoxaemia. J Physiol (Lond) 1919; 52: lxiii-lxiv.

- 9. Dew HR. Hydatid disease: its pathology, diagnosis and treatment. Sydney: Australasian Medical Publishing Company, 1928.

- 10. Kellaway CH, Morgan FG. The treatment of snake bite in Australia. Med J Aust 1931; 2: 482-485.

- 11. Winkel K, Mirtschin P, Pearn J. Twentieth century toxinology and antivenom development in Australia. Toxicon 2006; 48: 738-754.

- 12. Kellaway CH. Snake venoms. I. Their constitution and therapeutic applications. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp 1937; 60: 1-17.

- 13. Kellaway CH. Snake venoms. II. Their peripheral action. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp 1937; 60: 18-39.

- 14. Kellaway CH. Snake venoms. III. Immunity. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp 1937; 60: 159-177.

- 15. de Vahl Davis VA. History of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, 1915–1978: an examination of the personalities, politics, finances, social relations and scientific organization of the Hall Institute [PhD thesis]. Sydney: University of New South Wales, 1979.

- 16. Burnet FM. Charles Halliley Kellaway [obituary]. Med J Aust 1953; 1: 203-207.

- 17. Kellaway CH, personal service record. Series B2455. Canberra: National Archives of Australia, 1915-1920.

- 18. Courtice FC. Research in the medical sciences: the road to national independence. In: Home RW, editor. Australian science in the making. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988: 277-307.

- 19. Sexton C. Burnet: a life. 2nd ed. Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- 20. Hamersley H. Cancer, physics and society: interactions between the wars. In: Home RW, editor. Australian science in the making. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988: 197-219.

- 21. Lowe TE. The Thomas Baker, Alice Baker and Eleanor Shaw Medical Research Institute. Melbourne: Trustees of the Baker Medical Research Institute, 1974.

- 22. National Health and Medical Research Council. Walter and Eliza Hall Institute — application for subsidy. Series A1928/1, Control 690/20 Section 1. Canberra: National Archives of Australia, 1927-1934.

- 23. National Health and Medical Research Council. Walter and Eliza Hall Institute — application for subsidy. Series A1928/1, Control 690/20 Section 2. Canberra: National Archives of Australia, 1934-1938.

- 24. Gillespie JA. The price of health: Australian governments and medical politics 1910–1960. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

- 25. Roe M. The establishment of the Australian Department of Health: its background and significance. In: Cumpston JHL. The health of the people: a study in federalism. Canberra: Roebuck, 1978: v-xxiii.

- 26. Biological products. Serum lab diphtheria toxin. Death of children at Bundaberg. Enquiry and distribution of the Royal Commission Report. Series A1928/1, Control 90/28/3. Canberra: National Archives of Australia, 1928-1943.

- 27. Burnet FM, Kellaway CH. Recent work on staphylococcal toxins with special reference to the interpretation of the Bundaberg fatalities. Med J Aust 1930; 2: 295-301.

- 28. Park HW. Germs, hosts, and the origin of Frank Macfarlane Burnet’s concept of ‘self’ and ‘tolerance’, 1936–1949. J Hist Med Allied Sci 2006; 61: 492-534.

- 29. Hall AR, Bembridge BA. Physic and philanthropy: a history of the Wellcome Trust, 1936–1986. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

- 30. Parish HJ. The Wellcome Research Laboratories and immunisation: a historical survey and personal memoir. Chapter 22. c.1970. Located at: Wellcome Foundation Archive, Wellcome Library, London (WF/M/H/08/15).

Abstract

Charles Halliley Kellaway (1889–1952) was one of the first Australians to make a full-time career of medical research.

He built his scientific reputation on studies of snake venoms and anaphylaxis.

Under Kellaway’s directorship, the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute gained worldwide acclaim, and he played a critical role in its success between the world wars.

His administrative and financial strategies in the era before the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) helped local medical research weather the Depression and gain a strong foothold by World War II.