In Western countries, there is great public interest in the use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) for mainten-ance of health in general and for a number of chronic medical conditions, including cancer in particular — even though the cost of such treatment may be high.1 The reasons for such use are complex.2 Further, because of varying definitions, it is difficult to estimate accurately the prevalence of use of CAM. However, a systematic review suggested that between 7% and 64% of adult cancer patients in a variety of countries use such treatment.3 Two Australian surveys in the 1990s found that 22%4 and 52%5 of cancer patients used CAM. The most popular treatments were meditation, change in diet, and multivitamins.5 Published surveys have also shown that the types of CAM used vary widely both in time and place. For example popular treatments in the 1970s included Laetrile,6 in the 1980s high-dose vitamin C,7 and in the 1990s shark cartilage.8 In Canada, the herb essiac has been popular,9 and mistletoe in Germany,10 whereas the use of these substances in Australia seems to have been very limited.

In the current Australian context, it is noteworthy that, following a public inquiry into cancer services, the Australian Senate has recently recommended that information about complementary therapies should be more readily available and patients should have improved access to evidence-based complementary therapies.11

I have had the opportunity to study the promotion of CAM treatments from a different perspective to that usually reported, thanks to the cooperation of a prominent Australian politician and his widow. Accordingly, here I describe the types of treatments offered, unsolicited, to the politician when he made it public that he had developed lung cancer.

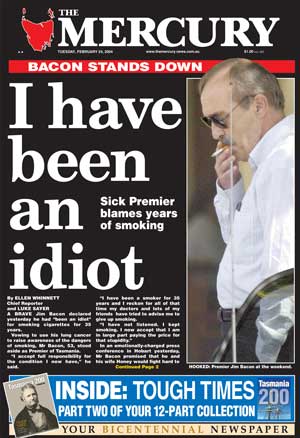

In February 2004, The Honourable Jim Bacon, Premier of Tasmania, aged 54, was diagnosed with advanced metastatic non-small cell lung cancer after a short history of dyspnoea and cough. He had been a heavy smoker. He made the diagnosis public, in the hope that by doing so he would contribute to the antismoking cause. Indeed, he famously pronounced on television “I have been an idiot” in not heeding advice to quit. Unfortunately, his disease responded only briefly to chemotherapy and radiotherapy and he died within 4 months of diagnosis.

After his public announcement, Bacon and his wife were deluged with letters of good wishes and encouragement. Among the many hundreds of pieces of correspondence were 157 that they identified as being proposals or suggestions for CAM use. Bacon had no interest in this type of treatment, and the material was offered to me for study and analysis.

The 157 pieces of CAM-related correspondence included letters, postcards, packages, emails, audiotapes, CDs, books and samples, and came from all parts of Australia and, in a few cases, from other countries.

I was able to categorise most of the correspondence, according to the system of the American Cancer Society (ACS),12 into five main groups (see Box), but with the addition of a sixth heading of “Medical systems”. This sixth category incorporated separately listed recommendations for non-Western and unorthodox medical systems, such as Chinese medicine or naturopathy. I included physical methods, a term encompassing practices such as “biomagnetic therapy” and an “energy cleaner machine”, under the ACS’s heading of “Manual healing and physical touch”.

In all, there were 143 pieces of correspondence recommending a multitude of unorthodox treatments that were categorised and are summarised in the Box. Among them were 20 books: 18 recommending methods incorporated into the table, and two compendia of CAM. The total number of treatments is greater than 143 as many correspondents proposed more than one method.

One correspondent advised Bacon to “take out alternative insurance — don’t rely entirely on the medical profession”. Among specific comments made, colloidal silver was recommended because “all cancer involves parasites”, and the Gerson diet was advocated because it was “based on the original nutrition that God gave Adam and Eve”.

Fourteen pieces of correspondence referred to private or secret methods, many of which would only be revealed to Bacon if he communicated directly with the correspondent (for example, “Give me a call — I have vital information for you”). In some cases, a fee was requested. Two correspondents, describing themselves as a “personal healer” and a “holistic practitioner”, respectively, invited Bacon to become one of their patients. Another correspondent said that he had cured himself of back pain and thus felt confident he could help; and yet another recommended The Oasis of Hope Hospital in Tijuana, Mexico. According to its website, this hospital specialises in alternative medicine, including in particular the use of Laetrile (see later). Bacon was also invited to become a distributor of health products.

This report shows that when a prominent politician publicly announced his illness he received many unsolicited communications that recommended a variety of unorthodox treatments. The treatments ranged from those for which some evidence of benefit exists to others with no evidence of benefit or evidence of harm, due to adverse interactions or their own specific dangers.

Unfortunately, most CAM treatments have not been subjected to thorough scientific evaluation. However, a recent Australian study has shown that patients will use CAM treatments in the absence of scientific evidence.5 A number of unsubstantiated methods found to be in use and classed as “radical”, including coffee enemas, faith healing, magneto-therapy, shark cartilage, high-dose vitamin C, oxygen and reiki, were among those suggested to Bacon.

For some of the treatments more commonly proposed, there is evidence of harm or of no benefit.

Laetrile, an extract of apricot pips said to possess “vitamin B17”, seems to have returned to popularity. This is despite its history of being one of the few forms of CAM that was thoroughly studied and shown to be ineffective. It was first popular in the 1970s, until negative studies were reported by the Mayo Clinic13 and the United States National Cancer Institute.6 It is dangerous, as apricot pips contain cyanide, and fatalities have been reported.14

The Hoxsey method consists of a mixture of numerous herbs taken either internally or externally. It is currently illegal in the United States as it is potentially dangerous.12 The external preparation generally contains caustic ingredients and the internal preparation contains buckthorn, a violent laxative, with potentially toxic amounts of iodine.15

Coffee enemas can cause electrolyte derangements,16 and several of the recommended diets may be nutritionally inadequate.

Shark cartilage was shown to be of no benefit in the treatment of cancer in a randomised controlled trial published this year.17 Before this, in 2000, as there was no evidence of benefit, the US Federal Trade Commission ordered two companies to cease selling shark cartilage as a cure for cancer, and fined one company one million dollars for false advertising in connection with shark cartilage sales.

Generally, there are concerns that some forms of CAM may not be subject to adequate levels of quality control, as the recent Australian experience involving Pan Pharmaceuticals has illustrated.

As most CAM treatments have not been subjected to thorough scientific evaluation, evidence of benefit or of no benefit has not been established.

Correspondents recommended that Bacon take “glyconutrients” (glycoproteins), either from a wide variety of food sources or as a supplement. The rationale for their use as a cancer treatment is not clear, as these glycoproteins are a diverse group of natural sugar-protein macromolecules found in or on all living cells. However, proponents suggest that several of the sugars that form such molecules are undersupplied in modern diets and that their provision in the form of “nutriceuticals” can have substantial immune modulating effects. There is some limited laboratory support for these claims,18 but clinical evidence is lacking.

Some of the treatments recommended, such as meditation, have been shown to be beneficial adjuncts to standard anticancer treatments.19,20 Others have been associated with sufficiently promising early results that they are the subject of ongoing scientific investigations. These include Ganoderma lucidum (reishi) mushrooms21,22 and xanthones extracted from the mangosteen plant.23

Among the treatments recommended to Bacon, several seem to be peculiar to, or especially prevalent in, Australia:

Percy’s powder, a trace mineral mixture, with a putative effect based on the hypothesis that cancer is due to excess phosphorus in the food chain, has also been used by its proponents to treat cancer in farm animals. Its creator, Percy Weston, died recently aged 100.

Ian Gawler, an Australian veterinarian cured of osteogenic sarcoma, now runs The Gawler Foundation, which operates a retreat in rural Victoria to promote “inner peace”.

In 1999, Giraffe World, an Australian company, was successfully prosecuted by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission for health fraud in connection with the marketing of a “negative ion” mat.

Most recently, a cancer treatment method promoted by Dr John Holt, a radiation oncologist from Perth, achieved prominence through a high-profile national television current affairs program. The method was subsequently investigated by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), which concluded that there was no evidence that it is superior to conventional cancer treatment, and that, in at least some areas, Dr Holt’s treatment is inferior.24

Medical practitioners who treat cancer patients need to be aware of the ready availability of CAM and the quandary that many patients may find themselves in when offered such treatments, often by well-meaning friends or relatives. It is now common for people to search the Internet for information about their disease. Using Google to search for the term “cancer cure” produces more than 20 000 000 hits (accessed November 2005), including several items about CAMs on the first page of results. Many websites discovered in this way may, at worst, be fraudulent or impart misleading information. Many forms of CAM are promoted as “natural” and thus claimed to be harmless, whereas in reality they may be dangerous.25

Adverse interactions between some forms of CAM, not necessarily recommended for cancer treatment, and cancer chemotherapy are well documented. For example St John’s wort, a popular herbal antidepressant, interferes with the effectiveness of irinotecan, a drug widely used for the treatment of colon cancer.26 Thus, practitioners should discuss any possible use of CAM for any indication with their patients. It is well known that patients are often reluctant to discuss their use of or concerns about CAM with their physicians;27 however, personal experience indicates that many are pleased to do so when given the opportunity.

Patients and practitioners alike require access to authoritative evidence-based advice on the potential benefits and adverse effects of the various types of CAM — such as that available on the websites of the American Cancer Society (http://cancer.org), the US National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (http://nccam.nih.gov) and the comprehensive (subscription-only) Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database (http://naturaldatabase.com).

Treatments proposed or recommended by the correspondents*

Type of treatment |

Number of suggestions |

||||||||||||||

Mind, body and spirit methods |

|

||||||||||||||

Meditation, visualisation, positive attitude, including Gawler’s method (n = 3), “avoid negativity” (n = 1) |

12 |

||||||||||||||

Laughter |

1 |

||||||||||||||

Manual healing and physical touch (including physical methods) |

|

||||||||||||||

Dr John Holt’s method (hyperthermia, radio waves) |

3 |

||||||||||||||

Others (1 each): Lee Crock’s aura therapy and energy cleaner machine; Dr Beck’s blood zapper and magnetic pulser; steam and cold water baths; Giraffe World’s negative ion mat; thermoregulatory hydrotherapy; biomagnetic therapy; microbeams |

7 |

||||||||||||||

Herbs, vitamins and minerals |

|

||||||||||||||

Laetrile/“vitamin B17” |

14 |

||||||||||||||

Glyconutrients, including ambrotose (n = 2) |

12 |

||||||||||||||

Ganoderma lucidum (reishi) mushrooms |

5 |

||||||||||||||

Vitamins in general |

4 |

||||||||||||||

Various herb combinations (horehound, wild cherry bark, saffron tea, others); Hoxsey herbal mixture |

5 |

||||||||||||||

Vitamin C |

2 |

||||||||||||||

Coffee enemas |

2 |

||||||||||||||

Others (1 each): antioxidants; shark cartilage; Avemar (Hungarian “medical micronutrients”); bee pollen; Ginkgo biloba; Herbalife (antioxidants); burdock; TBL12 (extract of sea cucumber); Aloe vera; Kombucha elixir (Mongolian tea); dimethylglycine |

11 |

||||||||||||||

Diet and nutrition methods |

|

||||||||||||||

Juices in general (including proprietary methods such as “Juice Plus”) |

11 |

||||||||||||||

Diet of Dr Johanna Budwig; flaxseed oil |

4 |

||||||||||||||

Noni juice |

3 |

||||||||||||||

General exhortation to improve nutrition |

2 |

||||||||||||||

Yoghurt |

2 |

||||||||||||||

“Grape cure” |

2 |

||||||||||||||

Cottage cheese |

2 |

||||||||||||||

Mangosteen juice |

2 |

||||||||||||||

Molasses |

2 |

||||||||||||||

Others (1 each): “Japanese missing nutrients”; green barley; wheatgrass; papaya juice; carrot juice; “White food diet”; cod liver oil; “Apple cider vinegar miracle health system”; broccoli, garlic and onions; liquorice; “Swiss diet” (fasting and juices); Chinese cancer busting diet of Professor Jane Plant; Gerson method; fasting; Graviola (from the Amazon); “pH balancing green food diet” |

17 |

||||||||||||||

Pharmacological and biological treatments |

|

||||||||||||||

Colloidal silver |

2 |

||||||||||||||

Others (1 each): “stabilised oxygen and aerobic oxygen”; Percy’s powder (mixture of trace elements); transfer factor from colostrum; Romanian pills; trypsin and chymotrypsin; “celloid mineral”; “insulin zone system”; coenzyme Q; “liver regeneration program” |

9 |

||||||||||||||

Medical systems |

|

||||||||||||||

Chinese medicine, including specifically Chinese herbs (n = 3), Qi Jong (n = 2), Tai Chi (n = 1), Zhuan Falun (book of Falun Gong practices) (n = 1), “Dr Chen” (n =1) |

12 |

||||||||||||||

German medicine: 1 each of German natural therapy and German New Medicine (“mind–body interaction” method of Dr Ryke Geerd Hamer) |

2 |

||||||||||||||

Others (1 each): ayurvedic medicine; Chakra healing; and naturopathy |

3 |

||||||||||||||

* Treatments are classified according to a modification of the system of the American Cancer Society (see text). |

|||||||||||||||

- 1. MacLennan AH, Wilson DH, Taylor AW. The escalating cost and preval-ence of alternative medicine. Prev Med 2002; 35: 166-173.

- 2. Lowenthal RM. Alternative cancer treatments [editorial]. Med J Aust 1996; 165: 536-537. <MJA full text>

- 3. Ernst E, Cassileth B. The prevalence of complementary/alternative medicine in cancer: a systematic review. Cancer 1998; 83: 777-782.

- 4. Begbie SD, Kerestes ZL, Bell DR. Patterns of alternative medicine use by cancer patients. Med J Aust 1996; 165: 545-548. <MJA full text>

- 5. Miller M, Boyer M, Butow P, et al. The use of unproven methods of treatment by cancer patients. Frequency, expectations and cost. Support Care Cancer 1998; 6: 337-347.

- 6. Ellison NM, Byar DP, Newell GR. Special report on Laetrile: the NCI Laetrile review. Results of the National Cancer Institute’s retrospective Laetrile analysis. N Engl J Med 1978; 299: 549-552.

- 7. Creagan ET, Moertel CG, O’Fallon JR, et al. Failure of high-dose vitamin C (ascorbic acid) therapy to benefit patients with advanced cancer. A controlled trial. N Engl J Med 1979; 301: 687-690.

- 8. Lowenthal RM. On eye of newt and bone of shark. The dangers of promoting alternative cancer treatments. Med J Aust 1994; 160: 323-324.

- 9. Boon H, Stewart M, Kennard MA, et al. Use of complementary/alternative medicine by breast cancer survivors in Ontario: prevalence and perceptions. J Clin Oncol 2000; 18: 2515-2521.

- 10. Munstedt K, Entezami A, Kullmer U. [Oncologic mistletoe therapy: physicians’ use and estimation of efficiency]. [German]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 2000; 125: 1222-1226.

- 11. Senate Community Affairs References Committee. The cancer journey: informing choice. Canberra: The Senate, 2005. Available at: http://www.aph.gov.au/Senate/committee/clac_ctte/cancer/report/index.htm (accessed Oct 2005).

- 12. American Cancer Society’s guide to complementary and alternative cancer methods. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, 2000.

- 13. Moertel CG, Fleming TR, Rubin J. A clinical trial of amygdalin (Laetrile) in the treatment of human cancer. N Engl J Med 1982; 306: 201-206.

- 14. Braico KT, Humbert JR, Terplan KL, Lehotay JM. Laetrile intoxication. Report of a fatal case. N Engl J Med 1979; 300: 238-240.

- 15. Cassileth BR. The alternative medicine handbook: the complete reference guide to alternative and complementary therapies. New York: WW Norton, 1998.

- 16. Green S. A critique of the rationale for cancer treatment with coffee enemas and diet. JAMA 1992; 268: 3224-3227.

- 17. Loprinzi CL, Levitt R, Barton DL, et al. Evaluation of shark cartilage in patients with advanced cancer: a North Central Cancer Treatment Group trial. Cancer 2005; 104: 176-182.

- 18. See DM, Cimoch P, Chou S, et al. The in vitro immunomodulatory effects of glyconutrients on peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Integr Physiol Behav Sci 1998; 33: 280-287.

- 19. Speca M, Carlson LE, Goodey E, Angen M. A randomized, wait-list controlled clinical trial: the effect of a mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction program on mood and symptoms of stress in cancer outpatients. Psychosom Med 2000; 62: 613-622.

- 20. Targ EF, Levine EG. The efficacy of a mind-body-spirit group for women with breast cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2002; 24: 238-248.

- 21. Ghafar MA, Golliday E, Bingham J, et al. Regression of prostate cancer following administration of Genistein Combined Polysaccharide (GCP), a nutritional supplement: a case report. J Altern Complement Med 2002; 8: 493-497.

- 22. Stanley G, Harvey K, Slivova V, et al. Ganoderma lucidum suppresses angiogenesis through the inhibition of secretion of VEGF and TGF-beta1 from prostate cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2005; 330: 46-52.

- 23. Moongkarndi P, Kosem N, Kaslungka S, et al. Antiproliferation, antioxidation and induction of apoptosis by Garcinia mangostana (mangosteen) on SKBR3 human breast cancer cell line. J Ethnopharmacol 2004; 90: 161-166.

- 24. Abbott T. Review of microwave cancer therapy. Media release ABB118/05. 29 September 2005. Available at: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/ministers/publishing.nsf/Content/health-mediarel-yr2005-ta-abb118.htm (accessed Oct 2005).

- 25. Ernst E. A primer of complementary and alternative medicine commonly used by cancer patients. Med J Aust 2001; 174: 88-92. <MJA full text>

- 26. Mathijssen RH, Verweij J, de Bruijn P, et al. Effects of St. John’s wort on irinotecan metabolism. J Natl Cancer Inst 2002; 94: 1247-1249.

- 27. Richardson MA, Masse LC, Nanny K, Sanders C. Discrepant views of oncologists and cancer patients on complementary/alternative medicine. Support Care Cancer 2004; 12: 797-804.

Abstract

When a prominent Australian politician, the then Premier of Tasmania, The Honourable Jim Bacon, publicly announced in February 2004 that he had lung cancer, he was inundated with well-wishing communications sent by post, email and other means. They included 157 items of correspondence recommending a wide variety of complementary and alternative medicines (CAMs).

The most common CAMs recommended were meditation, Chinese medicine, “glyconutrients”, juices, Laetrile and various diets and dietary supplements.

Although proof of benefit exists or promising preliminary laboratory studies have been carried out for a small number of the recommendations, no scientific evaluation has been performed for most of these treatments. Their potential benefits and harms are not known. Several recommendations were for treatments known to be useless, harmful or fraudulent.

Bacon’s experience suggests that cancer patients may receive unsolicited advice to adopt one or more forms of CAM. Both patients and practitioners need access to authoritative evidence-based information about the benefits and dangers of CAMs.