Previous surveys of the Australian community's knowledge of depression have shown that most people have little specific knowledge about depression or the effective pharmacological or psychological interventions available.1,2 However, the community has reported a preference for self-help strategies and expressed negative attitudes towards pharmacological interventions.3 Consistent with these views, people report that they prefer to consult family and friends, and other community-based supports, rather than general healthcare professionals or mental health experts.1

A range of factors is likely to be affecting the community's recent views and knowledge of depression. These include:

increased media coverage of depression-related topics;

increased rates of mental health interventions in primary care;4

public reports by high-profile people of their experiences with depression;

introduction of community- and school-based mental health awareness programs; and

widespread educational depression programs for primary care physicians5 and their patients.

The aims of this survey were to determine the degree of recognition and understanding of depression and its treatments in the Australian community in 2001, and to evaluate the extent to which demographic factors or personal experience are associated with awareness of and attitudes to depression.

A telephone survey of 900 respondents was conducted during 5–7 October 2001 across four States in Australia (New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, South Australia). Respondents were randomly selected within States using the Electronic White Pages (Marketing Pro 2.11, October 2000). Stratification ensured that the sample was representative of the normal population in terms of age, sex and geographic location across States by selecting respondents to match the Australian Bureau of Statistics records for age, sex and geographic location in 2001 (see http://www.abs.gov.au). The survey was designed by the investigators, and the telephone interviews were conducted by an independent contract company, Wallis Consulting Group (Melbourne, Victoria).

A 25-item survey was designed to measure four specific aspects of depression literacy:

In addition, the survey identified respondents' direct experience with depression (either themselves or a family member; 1 item) and other relevant demographic and geographic variables (8 items).

The interview commenced with the question What do you consider to be the major health problem(s) in Australia at present?. Although the traditional areas of cancer (22%, 413/1865) and heart disease (18%, 339/1865) featured prominently, the general public also rated obesity (10%, 185/1865) and alcohol or other substance misuse (7%, 128/1865) highly. Within the context of general health, mental health problems such as depression (2%, 31/1865), anxiety/stress/pressure (2%, 31/1865) or "all other major mental health problems" (2%, 44/1865) did not feature prominently. Various other issues were raised in response to this question, including problems with the Australian healthcare system (4%, 78/1865). Seven per cent (60/900) of people had no specific opinion. When all responses were ranked in terms of medical and mental disorders only (Box 1), the gap between traditional medical problems and mental health problems in terms of community recognition was obvious.

After answering the general health question, respondents were asked What do you consider to be the main health problems for youth (and, for the next question, for people aged over 70) in Australia? (see Box 1). Again, common mental health problems (eg, depression, anxiety/stress/pressure, suicidal behaviour) were not readily identified. For younger Australians, alcohol or other substance misuse was considered important, and, for older Australians, cognitive disorders were prominent after heart disease and cancer.

Next, respondents were asked What do you consider to be the major mental health problems for Australians?. Depression was spontaneously identified as the major mental health issue (39%, 560/1442), followed by anxiety/stress/pressure (18%, 264/1442), schizophrenia/psychosis (11%, 160/1442), dementia/Alzheimer's disease (6%, 90/1442) and alcohol or other substance misuse (5%, 73/1442). A significant proportion (14%, 122/900) indicated that they did not know of any major mental health problems in Australia. In particular, depression was likely to be identified as a major mental health problem by more women (60%, 329/550) than men (40%, 221/550; χ2 = 52.09; df = 1; P < 0.001). Furthermore, 65% (82/126) of respondents aged between 18–24 years rated depression as a major mental health problem, compared with 35% (54/153) of respondents aged over 65 years (χ2 = 24.54; df = 1; P < 0.001).

The debilitating nature of depression relative to other physical conditions was also recognised. When compared with diabetes, arthritis and asthma, depression was perceived to have the greatest impact on quality of life (or disability) for more than half the sample (55%, 486/889), with a further 21% (186/881) ranking it second in terms of disability. Further, depression was ranked as causing the most disability by people younger than 55 years (χ2 = 26.98; df = 1; P < 0.01) or people who had direct experience with depression, whether themselves or a family member (χ2 = 14.18; df = 1; P < 0.001).

In the second part of the survey, respondents were asked What do you think are the main signs or symptoms of depression? and How would you tell the difference between normal sadness and depression?. Importantly, 50% (449/900) of respondents could differentiate depression from normal sadness, indicating depression to be more intense (severity; n = 44), and constant or long lasting (duration; n = 405). There was less certainty regarding prevalence, with 64% (543/854) of the sample underestimating the lifetime prevalence of this disorder (ie, choosing rates of less than one in five).

With respect to common risk factors (Box 2), being unemployed (97%, 853/881), having a serious medical condition (95%, 827/867) and the birth of a child (72%, 601/840) were widely recognised as being "somewhat likely" or "very likely" to be associated with depression. There was less consistency regarding other risk and protective factors. For example, being married or in a relationship (which is a known protective factor) was thought to be a risk by 55% (429/774) of the sample. Having a job with lots of responsibility (which is not clearly a risk or protective factor) was rated as a risk by 67% (562/841) of respondents. Women and people who had experience with depression (either themselves or a family member) were more consistent and more likely to perceive many of these events or circumstances as "somewhat likely" or "very likely" to increase a person's risk of depression. For example, women (57%, 343/601) were more likely than men (43%, 258/601) to recognise the birth of a child as a risk factor (χ2 = 30.43; df = 1; P < 0.001).

People aged between 25 and 44 years perceived that the risk of depression was greater in the event of the birth of a child (χ2 = 6.80; df = 1; P < 0.05) or if living in a rural community (χ2 = 9.37; df = 1; P < 0.05). People aged over 65 years considered having a serious medical condition as a greater risk for depression (χ2 = 15.60; df = 1; P < 0.01).

When asked about the likely effects of various treatment approaches, respondents believed that both self-help (eg, exercise, yoga) and specific psychological strategies were highly likely to be helpful rather than harmful (Box 3). Similarly, natural remedies were thought of as largely helpful.

Among the pharmacotherapies, specific antidepressants rather than sleeping tablets or sedatives were rated as likely to be helpful. However, a quarter of respondents perceived antidepressants to be harmful. Women were more likely to regard antidepressant drugs as helpful for the treatment of depression (women, 57% [307/543] v men, 43% [236/543]; χ2 = 13.17; df = 2; P < 0.005), and people with personal or family experiences of depression were more likely to perceive psychological therapies to be helpful (60% [424/703] v 40% [279/703]; χ2 = 6.14; df = 2; P < 0.05). Although most respondents indicated that support from family and friends was helpful for alleviating depression, a greater proportion of those aged over 65 years (3%, 5/146) perceived this support to be harmful (χ2 = 15.19; df = 2; P < 0.05).

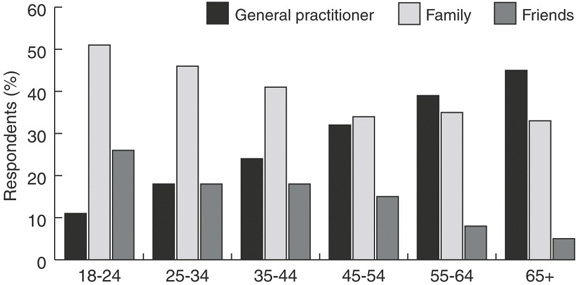

When asked If you thought you might be suffering from depression, who would you be most likely to turn to?, respondents rated family first (45%, 394/881), then GPs (28%, 250/881) and then friends (15%, 130/881). This stated preference varied with age: older people were more likely to see their GP as the most important resource (Box 4). However, given that most depressive disorders have their onset before 35 years of age, it is interesting that only 12% of 18–24-year-olds (15/126) and 19% (35/189) of 25–34-year-olds rated their GP as their first point of contact. Consistent with the general pattern of GP consultations in Australia, more women (34%, 154/452) reported that they were likely to seek initial assistance from a GP than men (21%, 96/448; χ2 = 17.93; df = 1; P < 0.05).

Of the respondents who identified family and friends as the people they would most likely turn to, when specifically asked . . . who would be your first point of (professional) contact?, 71% (340/476) of respondents identified GPs. Smaller percentages of people reported that they would see a counsellor (9%, 43/476), clinical psychologist (5%, 25/476), priest/clergy (3%, 14/476) or specialist psychiatrist (2%, 9/476).

When asked If you were depressed, what would be your first choice of treatment?, respondents indicated a preference for non-pharmacological treatments (Box 5). Counselling and support from others were the overall treatments of choice, with women in particular identifying counselling. Men were significantly more likely to go out and socialise, go to the pub/have a drink or smoke pot.

Box 5 also indicates low levels of knowledge regarding appropriate treatment options. Importantly, 23% (212/900) of respondents indicated that they "did not know" what their first choice of treatment would be, and a further 13% (113/900) identified only contacting a healthcare professional.

Our survey shows that the Australian community does not view mental health (other than alcohol or other substance misuse) as one of its major general health issues. Traditional health areas (eg, cancer, heart disease) attract greatest recognition. Interestingly, alcohol and other substance-misuse problems attracted a high degree of recognition, even though they have less effect on disability and healthcare costs than common mental health problems.6-8 Although health policy initiatives in Australia have promoted the notion of integrating mental health services within general healthcare,9 we are yet to see the evidence of community recognition of this concept. Even high-profile topics, such as youth suicide, did not receive much recognition. This was the case even for the specific ratings of health problems for youth in Australia. A key goal for mental health initiatives will therefore be to present depression and other mental disorders not just as major mental health problems, but as major general health problems facing the Australian community.10-12

When compared with previous surveys,1,2 some common and persistent themes emerged. Depression was viewed as a common and potentially disabling mental health problem. Awareness and understanding, however, was strongly influenced by female sex, younger age and prior personal or family experience of depression. Interestingly, 58% of the population identified themselves as having personal or family experience. Given the ongoing stigma associated with even the common forms of mental disorder,13 this high rate of personal disclosure is encouraging.

For people with depression to gain the maximum benefit from healthcare services, they need to have some knowledge about depression and implement certain behaviours. These include:

recognising symptoms as indicating an illness (rather than a personal failing);

presenting for assessment early;

adhering to efficacious interventions; and

establishing long-term partnerships with general practitioners and other mental health professionals.14

In a recent Australian community study, more than half the people who were identified as having common mental disorders, such as depression or anxiety (typically having symptoms for at least six months and eight "days out of role in the last month"), had not consulted a professional for a mental health problem.15

In our survey, attitudes toward help-seeking behaviour and treatments were largely consistent with previous surveys.1 When asked to identify a first choice of treatment for depression, people in this study reported a strong preference for self-help and non-pharmacological strategies and a heavy reliance on family, friends and non-professional therapists. Importantly, positive views of psychological therapies were stronger in respondents with experiences of depression. It will be increasingly important for medical providers to recognise the community's desire for non-medical and alternative treatments and attempt to provide accurate information16 about the benefits and costs of such approaches.

Although GPs were identified as the preferred point of medical contact, most people (especially younger people) were highly reliant on family and friends. Consequently, the knowledge and attitudes of family and friends will have strong effects on the experiences of people with depression.13 Although the role of the GP was emphasised, and this has a wide range of other possible population health and integrated medical care implications,17 healthcare professionals were not high on the list of providers of treatments. Many people still have very little understanding of treatment options or the healthcare services available.

Attitudes toward antidepressant drugs (but not sedative drugs) appear to be less negative than in previous years.1 However, as the methodology used in this survey is not directly comparable with past surveys, this must be considered as a tentative impression only. The potential effect of using the term "antidepressant" in the current survey might have contributed to a more positive response. There are other reasons to believe that attitudes may be improving. These include wider community experience (and, presumably, some positive experiences) with newer antidepressant agents,18 and more active discussion in the media about the potential benefits and risks of the widespread prescribing of these agents.19

1: Most frequently identified medical and mental disorders by 900 Australian adults

All medical and mental disorders |

Major health problems* (% [n]) |

||||||||||

For all Australians |

For younger Australians |

For older Australians |

|||||||||

Cancer |

32% (413) |

3% (23) |

21% (222) |

||||||||

Heart disease and other vascular risks |

26% (339) |

0 |

30% (326) |

||||||||

Alcohol or other substance misuse |

10% (128) |

55% (411) |

1% (12) |

||||||||

Diabetes |

8% (108) |

2% (17) |

8% (88) |

||||||||

Infectious diseases (including HIV/AIDS) |

6% (78) |

8% (58) |

0.5% (5) |

||||||||

Asthma |

5% (58) |

7% (49) |

0.3% (3) |

||||||||

Mental health (not specified) |

3% (33) |

4% (33) |

2% (19) |

||||||||

Depression |

2% (31) |

7% (52) |

1% (10) |

||||||||

Anxiety/stress/pressure |

2% (31) |

3% (21) |

1% (6) |

||||||||

Dementia/Alzheimer's disease |

0.7% (9) |

0 |

11% (117) |

||||||||

Arthritis |

0.7% (9) |

0 |

11% (112) |

||||||||

Gambling |

0.3% (5) |

0 |

0 |

||||||||

Eating disorders |

0.3% (4) |

3% (21) |

0.1% (1) |

||||||||

Accident/injury |

0.2% (3) |

3% (20) |

0.1% (1) |

||||||||

Suicide |

0.1% (1) |

0.5% (4) |

0 |

||||||||

Schizophrenia/psychosis |

0.1% (1) |

0.5% (4) |

0 |

||||||||

Other |

3% (41) |

4% (26) |

13% (141) |

||||||||

Total |

100% (1292) |

100% (739) |

100% (1063) |

||||||||

* Each participant had the opportunity to provide more than one response (ie, What do you consider to be the major health problem in Australia at present?; Are there any other major health problems in Australia?). |

|||||||||||

2: Perceived impact of events or circumstances on the likelihood of experiencing depression, as rated by 900 Australian adults

Events/circumstances |

n |

Percentage (number) of respondents |

χ2 |

||||||||

Very likely |

Somewhat likely |

Somewhat unlikely |

Very unlikely |

||||||||

Known true risk factors* |

|||||||||||

Being unemployed |

881 |

69% (609) |

28% (244) |

2% (15) |

1% (13) |

772.5 |

|||||

Having a serious medical condition |

867 |

60% (518) |

35% (309) |

3% (26) |

2% (14) |

714.3 |

|||||

Birth of a child |

840 |

27% (229) |

44% (372) |

17% (139) |

12% (100) |

156.0 |

|||||

Neutral factors† |

|||||||||||

Having a job with lots of responsibility |

841 |

24% (204) |

43% (358) |

24% (204) |

9% (75) |

95.2 |

|||||

Living in a rural area |

818 |

19% (158) |

44% (355) |

22% (183) |

15% (122) |

52.9 |

|||||

Protective factors‡ |

|||||||||||

Being married or in a relationship |

774 |

15% (113) |

41% (316) |

29% (229) |

15% (116) |

9.1 |

|||||

Denominators vary because of missing data. |

|||||||||||

3: Perceived helpfulness of treatments for depression, as rated by 900 Australian adults

Treatment |

n |

Percentage (number) of respondents |

χ2 |

||||||||

Helpful |

Harmful |

Neither |

|||||||||

Support from family and friends |

894 |

97% (872) |

1% (7) |

2% (15) |

1658.5 |

||||||

Exercise |

884 |

91% (807) |

1% (3) |

8% (74) |

1344.7 |

||||||

Yoga |

832 |

87% (725) |

2% (17) |

11% (90) |

1093.5 |

||||||

Psychological therapies |

823 |

87% (717) |

4% (30) |

9% (76) |

1075.3 |

||||||

Psychotherapy |

801 |

81% (647) |

7% (59) |

12% (95) |

814.0 |

||||||

Natural remedies (eg, vitamins, diet) |

858 |

72% (614) |

3% (28) |

25% (216) |

626.0 |

||||||

Antidepressant medications |

857 |

65% (554) |

25% (217) |

10% (86) |

408.1 |

||||||

St John's wort |

534 |

59% (316) |

6% (29) |

35% (189) |

232.4 |

||||||

Self-help book |

862 |

57% (495) |

10% (84) |

33% (283) |

294.0 |

||||||

Sleeping tablets/sedatives |

851 |

25% (216) |

55% (469) |

20% (166) |

186.0 |

||||||

Denominators vary because of missing data. Between-group differences analysed using χ2 tests (df = 2). For all comparisons, P < 0.001. |

|||||||||||

4: People from whom Australian adults would first seek help for depression, by age group

Responses of 900 people to the question If you thought you might be suffering from depression, who would you be most likely to turn to?.

5: Identified first choice of treatment if personally depressed,* as rated by 900 Australian adults

Choice of treatment |

Total responses (% [n]) |

||||||||||

Pharmacological therapy |

|||||||||||

Not specified |

7% (67) |

||||||||||

Natural remedies |

2% (21) |

||||||||||

Antidepressants |

2% (19) |

||||||||||

Non-pharmacological therapy |

|||||||||||

Counselling |

21% (186) |

||||||||||

Behaviour therapy |

1% (7) |

||||||||||

Support groups |

1% (6) |

||||||||||

Psychotherapy |

1% (5) |

||||||||||

Seek professional help |

|||||||||||

General practitioner |

9% (79) |

||||||||||

Psychologist |

2% (18) |

||||||||||

Psychiatrist |

2% (16) |

||||||||||

Priest/clergy |

1% (5) |

||||||||||

Seek social support |

|||||||||||

Not specified |

8% (68) |

||||||||||

Family |

4% (39) |

||||||||||

Friends |

3% (29) |

||||||||||

Lifestyle adjustments |

|||||||||||

Self-help strategies |

4% (35) |

||||||||||

Socialise more |

3% (30) |

||||||||||

Relax |

2% (19) |

||||||||||

Have a drink/smoke pot |

2% (15) |

||||||||||

Exercise |

1% (12) |

||||||||||

Other |

1% (12) |

||||||||||

Don't know |

23% (212) |

||||||||||

Total |

100% (900) |

||||||||||

* Response to the question If you were depressed, what would be your first choice of treatment?. |

|||||||||||

- Nicole J Highet1

- Ian B Hickie2

- Tracey A Davenport3

- 1 beyondblue: the national depression initiative, Melbourne, VIC.

- 2 School of Psychiatry, University of New South Wales at St George Hospital, Sydney, NSW.

The assistance of Cristina Ricci with the preparation of this article was greatly appreciated.

- 1. Jorm AF, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, et al. 'Mental health literacy': a survey of the public's ability to recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. Med J Aust 1997; 166: 182-186. <eMJA full text>

- 2. Goldney RD, Fisher LJ, Wilson DH. Mental health literacy: an impediment to the optimum treatment of major depression in the community. J Affect Disord 2001: 64; 277-284.

- 3. Jorm AF, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, et al. Helpfulness of interventions for mental disorders: beliefs of health professionals compared with the general public. Br J Psychiatry 1997; 171: 233-237.

- 4. Britt HC, Miller GC. The BEACH study of general practice. Med J Aust 2000; 173: 63-64.

- 5. Naismith SL, Hickie IB, Scott EM, Davenport TA. Effects of mental health training and clinical audit on general practitioners' management of common mental disorders. Med J Aust 2001; 175 Suppl Jul 16: S42-S47.

- 6. Henderson S, Andrews G, Hall W. Australia's mental health: an overview of the general population survey. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2000; 34: 197-205.

- 7. Hickie IB, Koschera A, Davenport TA, et al. Comorbidity of common mental disorders and alcohol or other substance misuse in Australian general practice. Med J Aust 2001; 175 Suppl Jul 16: S31-S36.

- 8. Teesson M, Hall W, Lynskey M, Degenhardt L. Alcohol- and drug-use disorders in Australia: implications of the National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2000; 34: 206-213.

- 9. Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care. National Mental Health Report 2000: Sixth Annual Report. Changes in Australia's Mental Health Services under the First National Mental Health Plan of the National Mental Health Strategy 1993–98. Canberra: Mental Health and Special Programs Branch, Department of Health and Ageing, 2000.

- 10. Andrews G. Should depression be managed as a chronic disease? BMJ 2001; 322: 419-421.

- 11. Murray CJL, Lopez AD, editors. The global burden of disease: a comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from diseases, injuries and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996.

- 12. Andrews G, Henderson S, Hall W. Prevalence, comorbidity, disability and service utilisation. Overview of the Australian National Mental Health Survey. Br J Psychiatry 2001; 178: 145-153.

- 13. McNair BG, Highet NJ, Hickie IB, Davenport TA. Exploring the perspectives of people whose lives have been affected by depression. Med J Aust 2002; 176 Suppl May 20: S69-S76. <eMJA full text>

- 14. Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al. Population-based care of depression: effective disease management strategies to decrease prevalence. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1997; 19: 169-178.

- 15. Andrews G, Carter GL. What people say about their general practitioners' treatment of anxiety and depression. Med J Aust 2001; 175 Suppl Jul 16: S48-S51.

- 16. Jorm AF, Christensen H, Griffiths KM, Rodgers B. Effectiveness of complementary and self-help treatments for depression. Med J Aust 2002; 176 Suppl May 20: S97-S104. <eMJA full text>

- 17. Hickie IB, Davenport TA, Naismith SL, Scott EM on behalf of the SPHERE National Secretariat. Conclusions about the assessment and management of common mental disorders in Australian general practice. Med J Aust 2001; 175 Suppl Jul 16: S52-S55.

- 18. McManus P, Mant A, Mitchell PB, et al. Recent trends in the use of antidepressant drugs in Australia, 1990-1998. Med J Aust 2000; 173: 458-461.

- 19. Hickie IB. Depressed Australians: should we worry? [letter]. Med J Aust 2001; 174: 425-426.

Abstract

Objectives: To determine the degree of recognition and understanding of depression and its treatments in Australia in 2001, and detail factors and personal experiences that influence awareness of and attitudes to depression.

Design and setting: Cross-sectional survey of a representative community sample (900 randomly selected respondents), via telephone interview, conducted 5–7 October 2001.

Main outcome measures: Reports of community awareness, knowledge and attitudes to depression and its treatments in Australia.

Results: The Australian community does not view mental health as a major general health issue. When asked specifically, depression was recognised as the most common mental health problem. Recognition of depression was greater among women and younger people. Most people (58%; 508/879) reported that they or a family member had experienced depression. People younger than 55 years and people with personal or family experiences of depression viewed depression as more disabling than other chronic medical conditions. Half the respondents differentiated depression from normal sadness. Awareness of common risk versus protective factors was limited. Most people endorsed a preference for self-help and non-pharmacological treatments, but community views of antidepressant drugs were less negative than expected. General practitioners were identified as the preferred point of first contact among healthcare professionals.

Conclusions: Although mental health is still not highlighted as a major health issue, Australians do recognise depression as the major mental health problem. Women and younger people have more substantial knowledge about key aspects of depression and its treatments.