The disparity in health between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia and their non-Indigenous peers is core business for the Aboriginal community controlled health service (ACCHS) sector. The Closing the Gap framework commits to reducing this disadvantage, with cross-government-sector initiatives and investment, reflecting the need to improve the social and emotional wellbeing of the Aboriginal community.1 Activity in the primary health care sector, with its focus on prevention, early intervention and coordination of care complements these efforts to build healthier communities. With their model of comprehensive primary health care and community governance, ACCHSs have reduced unintentional racism, barriers to access to health care, and are progressively improving individual health outcomes for Aboriginal people.

So what is known about the performance of ACCHSs and mainstream general practice? Why should support for ACCHSs be both continued and enhanced?

Models of care and program delivery

The models of comprehensive primary health care, developed with government and research partners, that are used in ACCHSs are well described.2,3 Clinical services, health promotion, cultural safety, community engagement all underpinned by research, evaluation and planning activity are the essential components in these models. In addition, particularly for maternal and child health, models of family-centred primary health care3-5 extend comprehensive team-based care of individuals to members of families or households, often with outreach services. These models complement the resources, time and evidence base needed to manage more problems of greater complexity at each consultation6 than are usually seen in mainstream general practices.

The patient-centred medical home (PCMH) model,7 now suggested as best practice for general practice,8,9 is not dissimilar to the model used by ACCHSs since their inception in the 1970s.10 Leadership in ACCHS involves both ACCHS management and the community, and the care model is more team-based than general practitioner-focused. Nonetheless, the ACCHS and PCMH models have much in common. Care: is patient-focused; may encompass the family; has significant physician input; is integrated with allied health specialists, mental health professionals and community services, preferably delivered in the home; and is underpinned by participation in clinical quality-improvement programs. Importantly, with increasing regionalisation and with government policy supporting more community-driven models of care (with the advent of Medicare Locals and Health and Hospital Networks), the ACCHSs provide prototypes for community-operated health services.

Access

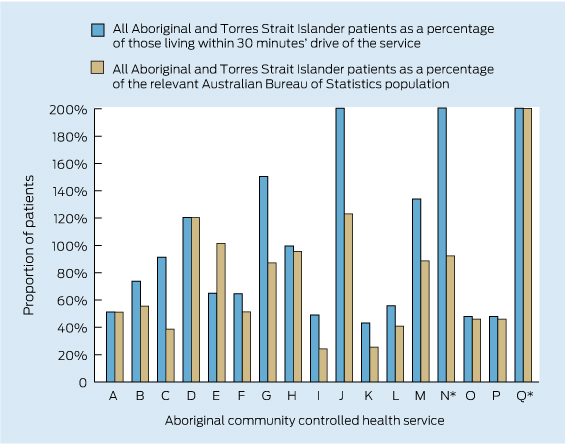

Do Aboriginal people use general practices more than ACCHSs as is sometimes claimed?11 In Queensland, 27 ACCHSs are spread across a diverse, decentralised area of 1.7 million square kilometres. The service data suggest that, in regional areas, the use of ACCHSs by people identifying as Aboriginal may be higher than the 50–50 split with general practice indicated by Medicare Australia data.12 Employing various strategies such as the Practice Incentives Program copayments, social marketing campaigns and targets set in a clinical quality-improvement (CQI) collaborative, ACCHSs in Queensland have been increasing their patient enrolments.

Based on Australian Bureau of Statistics-estimated catchment data for the Queensland services by local government areas or by drive time,13 the number of Aboriginal patients making one visit in 2 years to these regional ACCHSs is higher than the resident Indigenous population (Box 1). For 11 of 17 services, over 60% of Aboriginal people living in their catchments within a 30-minute drive had visited in the 2 years to September 2012; for six of these ACCHSs, all classified Remoteness Area 2 or 3, the data suggest up to 100% of the Aboriginal population living within a 30-minute drive are using their services, with many patients travelling longer than 30 minutes. Coverage is lower in the large metropolitan centres, for example in Brisbane where three ACCHSs serve a population of 40 000.

Access to services is critical and, where ACCHSs exist, the community prefers to and does use them,14 suggesting that patterns of use reflect patchy supply.

Need

There are ongoing drivers of ill health among adult Aboriginal patients who use ACCHSs. In Queensland, 49% of adults remain current tobacco users, over 70% are overweight or obese, 25% have hypertension, and 18% have type 2 diabetes mellitus.15 These problems must be tackled by individuals, families and the community. To effect change, health providers need well resourced allied health teams, preferably operating from their clinics, where people feel respected and are given assistance with transport.4 Sustaining programs run by the Tobacco and Health Life Style teams established in ACCHSs from 201016 will continue to support downward trends, for example, in tobacco use.

Traditional general practice is ill equipped to deal with ongoing problems in Aboriginal health and the necessary complex challenges in behaviour change.

Quality of care, evaluation and performance

The medical literature has many reports of well implemented research programs, often integrated with everyday care in ACCHSs, showing improved health outcomes. Sexual health,17 maternal and child health,18 smoking cessation19 and cardiovascular programs20,21 have been successfully run and monitored in ACCHSs. Recently ACCHSs have been building their capacity to collect and use health service data, enabling review of service delivery, performance tracking and monitoring of the health status of their patient cohorts.

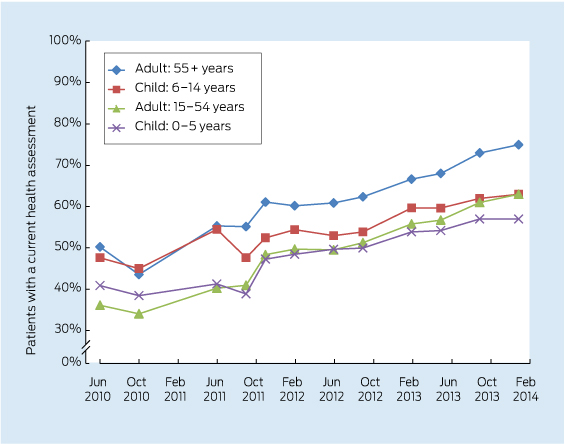

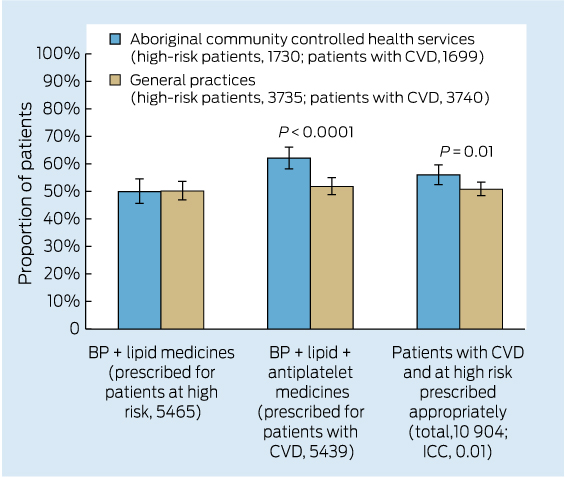

Care delivered in ACCHSs for prevention and chronic disease management appears to be equal to if not better than that delivered by general practices. Queensland Aboriginal and Islander Health Council (QAIHC) data show good performance in risk factor monitoring and the management of hypertension and chronic disease.15 Box 2 shows improving performance in completion of health assessments — a first step in prevention activity— over the past 4 years.22 The Torpedo study, a randomised controlled trial of the use of an electronic decision-support system measuring absolute cardiovascular risk, shows ACCHSs outperforming general practices in managing risk.21 Data collected in late 2011 show that the ACCHSs sites had significantly more patients at high risk being prescribed best-practice medications than the general practice sites at baseline, and this gap was sustained through the intervention period (Box 3).23

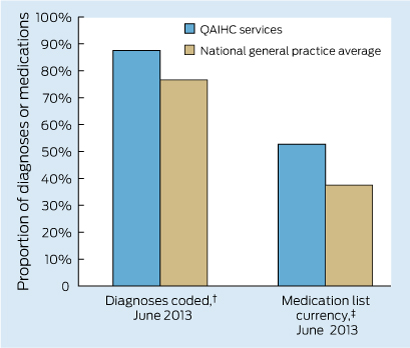

Data from the Australian Primary Care Collaboratives (APCC) program, often not published, can examine performance between ACCHSs and general practice clusters. Data for 2012, from Wave 2 of the APCC e-health program, show that ACCHSs in Queensland had more diagnoses coded (as opposed to use of free text) in medical histories and a higher proportion of medications on their current medication lists prescribed within the preceding 6 months than their general practice counterparts (Box 4). This pattern is similar to that reported for cardiac and diabetes care in 20113 and seen in recent years in the QAIHC Closing the Gap Collaborative, where ACCHSs were the higher performers in identification of risk factors and completion of health checks (K Panaretto, unpublished data). These data reflect the commitment to delivering evidenced-based care by clinical teams and the voluntary participation in clinical quality-improvement programs seen in ACCHSs, resulting in these services leading the primary health care sector in monitoring clinical performance.

Workforce and training

ACCHSs are significant employers of Indigenous people. In 2012, the 150 ACCHSs employed nearly 4000 people nationally. Of these, some 95% of health workers, 85% of drivers and 32% of allied health professionals (55% overall) identified as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander. The proportion of Indigenous doctors and nurses remains low (5% and 10%, respectively).24 The Leaders in Indigenous Medical Education (LIME) Network has recently signed an agreement with the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation seeking to increase Aboriginal medical student placements in Indigenous primary health care settings with a view to increasing participation in and enhancing the effectiveness of the medical workforce. Similar initiatives are underway in nursing, including innovative programs that are graduating new cohorts of Indigenous midwives.25 In addition, the ACCHSs have always had a major role in Aboriginal health worker (AHW) training, and the introduction of national AHW registration will standardise the quality of this important component of the health workforce.26 The services' ability to deal with the impact of social determinants and lower health literacy is due, in part, to ACCHSs being significant providers of Aboriginal employment and training.

The way forward

When challenged to deliver best-practice care, ACCHSs have risen to the task, assuming a rightful place in the broader Australian health system. Based on the evidence available, health care delivered by ACCHSs is of a high standard, compares favourably with mainstream services on key aspects of clinical care and warrants continued funding support. ACCHSs are committed to improving the health of their communities, leading the way with improved governance and use of data to ensure they deliver the best evidence-based services possible today. They are focused on delivering systematic patient-centred care and are embracing innovations in e-health, the personally controlled electronic health record and electronic prescribing, to promote continuity of care and coordination across ACCHSs and mainstream services.

In view of the possible cuts to funding to the ACCHSs sector with the rationalisation of Indigenous programs announced in the recent Budget, the data suggest that to enhance the quality of care and reach national targets requires:

- policy and funding support to provide additional ACCHSs in both regional and metropolitan areas, where there are currently large populations with poor access to comprehensive primary health care;

- recurrent funding support for initiatives to sustain clinical and administrative quality-improvement programs; and

- mainstream primary health care providers continuing to enhance their recognition of their Aboriginal patients through clinical quality-improvement initiatives and by partnering with the community controlled sector to monitor performance and value across both sectors.

In conclusion, ACCHSs are key players in the Indigenous community in exercising self-determination, taking responsibility in action, improving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health, and setting the frameworks to underpin the shift to healthy or well communities. The government must acknowledge and continue to support ACCHSs as leaders in Aboriginal primary health care.

2 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults who regularly attended participating health services in Queensland between February 2010 and January 2014 and who had a current health assessment*22

* A comprehensive review of patients' health (Medicare Item 715) within the past 2 years (formerly the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health check).

3 Baseline data for the Torpedo study23 before random allocation — management of patients with high cardiovascular risk or established cardiovascular disease in 40 general practices and 20 Aboriginal community controlled health services for the 12 months to May 2012

BP = blood pressure. CVD = cardiovascular disease. ICC = intraclass correlation coefficient.

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- Kathryn S Panaretto1,2

- Mark Wenitong2,3

- Selwyn Button1

- Ian T Ring4

- 1 Queensland Aboriginal and Islander Health Council, Brisbane, QLD.

- 2 National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation, Canberra, ACT.

- 3 Apunipima Cape York Health Council, Cairns, QLD.

- 4 Australian Health Services Research Institute, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, NSW.

We thank Amy Dellit of the Australian Primary Health Care Research Institute Centre for Research Excellence in Prevention of Chronic Conditions in Rural and Remote High Risk Populations for the data analysis undertaken at QAIHC for this article.

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Council of Australian Governments. Closing the Gap in Indigenous Disadvantage. Canberra: COAG, 2008. http://www.coag.gov.au/closing_the_gap_in_indigenous_disadvantage (accessed Jan 2014).

- 2. Tilton E, Thomas D. Core functions of primary health care: a framework for the Northern Territory. Darwin: Northern Territory Aboriginal Health Forum, 2011.

- 3. Australia Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare. Windows into safety and quality in health care. Safe and high quality care 2010. Sydney: ACSQHC, 2010. http://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/Windows-2010-Web-version.pdf (accessed Jan 2014).

- 4. Peiris D, Brown A, Howard M, et al. Building better systems of care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: findings from the Kanyini health systems assessment. BMC Health Serv Res 2012; 12: 369.

- 5. A blueprint for Aboriginal and Islander Health Reform in Queensland. Brisbane: Queensland Aboriginal and Islander Health Council, 2011. http://www.qaihc.com.au/resources/publications/ (accessed May 2014)

- 6. Larkins SL, Geia LK, Panaretto KS. Consultations in general practice and at an Aboriginal community controlled health service: do they differ? Rural Remote Health 2006; 6: 560.

- 7. Stange KC, Nutting PA, Miller WL, et al. Defining and measuring the patient-centered medical home. J Gen Intern Med 2010; 25: 601-612.

- 8. Department of Health and Ageing. Primary Health Care Reform in Australia. Report to Support Australia's First National Primary Health Care Strategy. Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing, 2009 http://www.yourhealth.gov.au/internet/yourhealth/publishing.nsf/content/report-primaryhealth (accessed Jan 2014).

- 9. Jackson CL. Australian general practice: primed for the “patient-centred medical home”? Med J Aust 2012; 197: 365-366. <MJA full text>

- 10. Perspectives on Aboriginal community controlled health services. Med J Aust 2006; 184: 526. <MJA full text>

- 11. Australian Health Ministers' Advisory Council. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework 2012 Report. Canberra: AHMAC, 2012.

- 12. Deeble J. Assessing the health service use of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing, 2009. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/nhhrc/publishing.nsf/Content/16F7A93D8F578DB4CA2574D7001830E9/$File/John%20Deeble%20Indigenous%20paper%20June%202009.pdf (accessed Jan 2014).

- 13. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Population distribution, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, 2006. http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/4705.02006 (accessed Jan 2014).

- 14. Taylor AW, Marin T, Avery J, Dal Grande E. South Australian Aboriginal Health Survey. Adelaide: Population Research and Outcome Studies, 2012.

- 15. Panaretto KS, Gardner KL, Button S, et al. Prevention and management of chronic disease in Aboriginal and Islander Community Controlled Health Services in Queensland: a quality improvement study assessing change in selected clinical performance indicators over time in a cohort of services. BMJ Open 2013; 3: e002083.

- 16. Department of Health and Ageing. Closing the Gap. Tackling Indigenous chronic disease. National action to reduce Indigenous smoking rate. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/ctg/publishing.nsf/Content/national-action-to-reduce-indigenous-smoking-rate (accessed Jan 2014).

- 17. Ward J, McGregor S, Guy RJ, et al. STI in remote communities: improved and enhanced primary health care (STRIVE) study protocol: a cluster randomised controlled trial comparing ‘usual practice' STI care to enhanced care in remote primary health care services in Australia. BMC Infect Dis 2013; 13: 425.

- 18. Panaretto KS, Mitchell MR, Anderson L, et al. Sustainable antenatal care services in an urban Indigenous community: the Townsville experience. Med J Aust 2007; 187: 18-22. <MJA full text>

- 19. Eades SJ, Sanson-Fisher RW, Wenitong M, et al. An intensive smoking intervention for pregnant Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women: a randomised controlled trial. Med J Aust 2012; 197: 42-46. <MJA full text>

- 20. Liu H, Patel A, Brown A, et al. Rationale and design of the Kanyini guidelines adherence with the polypill (Kanyini-GAP) study: a randomised controlled trial of a polypill-based strategy amongst indigenous and non indigenous people at high cardiovascular risk. BMC Public Health 2010; 10: 458.

- 21. Peiris D, Usherwood T, Panaretto K, et al. The Treatment of cardiovascular Risk in Primary care using Electronic Decision supOrt (TORPEDO) study-intervention development and protocol for a cluster randomised, controlled trial of an electronic decision support and quality improvement intervention in Australian primary healthcare. BMJ Open 2012; 2: e002177.

- 22. Data Management Unit — Preventative Health Unit, Queensland Aboriginal and Islander Health Council. External Report 3. Aboriginal and Islander Community Controlled Health Services Clinical Excellence (ACE) Program. Brisbane: QAIHC, 2014: 19. http://www.qaihc.com.au/resources/publications/ (accessed Jun 2014).

- 23. Panaretto KS, Peiris D, Hunt J, et al. HealthTracker: does electronic decision support improve identification and management of cardiovascular risk in Australian primary health care. World Congress of Cardiology Scientific Sessions; 2012 Apr 18-21; Dubai, UAE: E808.

- 24. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health services report, 2010–11: OATSIH services reporting - key results. Canberra: AIHW, 2012. http://www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=10737423052 (accessed Jan 2014).

- 25. NSW Health. To grow dturali — Aboriginal careers in nursing and midwifery. Sydney: NSW Health, 2011. http://www0.health.nsw.gov.au/resources/nursing/projects/pdf/aboriginal_careers_namo_h.pdf (accessed Jan 2014).

- 26. Health Workforce Australia. Growing our future: the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Worker Project Final Report. Adelaide: HWA, 2011. https://www.hwa.gov.au/sites/uploads/a-tsi-hwa-final-report-201208.pdf (accessed Jan 2014).

Summary